With the Covid-19 Omicron surge largely behind us and the corresponding steep drop in the Covid-19 positivity rate on campus, MIT has begun loosening some Covid-19 related restrictions. Perhaps most notable is the move from mandatory to optional testing for all faculty and employees, and the drop from twice-a-week testing to once-a-week testing for students and residents.

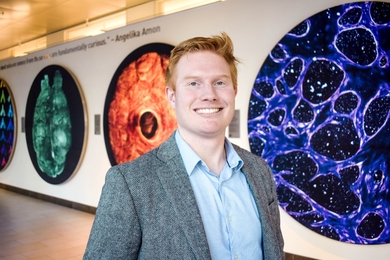

In a recent discussion, Cecilia Stuopis, director of MIT Medical; Anette “Peko” Hosoi, the Neil and Jane Pappalardo Professor of Mechanical Engineering; and Ian A. Waitz, vice chancellor for undergraduate and graduate education, offered some additional insight into MIT’s recent policy decision and their hope for a gradual return to normalcy.

Q: As Covid-19 cases have been declining at MIT and in the surrounding community, what does that tell us about the state of the pandemic? Should people modify their behaviors?

Cecilia Stuopis: Right now, things are looking better than they have in several months. Wastewater data for the greater Boston area, an excellent, unbiased indicator, shows that the rate of Covid-19 infection in surrounding communities is decreasing rapidly. The prevalence is on par now with the start of the fall semester. While the virus is still with us, it seems clear that the Omicron wave has largely passed.

Thanks to our vaccine and booster mandate, the MIT community made it through the recent surge well. Although more than 4,000 of us were diagnosed with Covid-19 in the past few months, we know of no Omicron-related hospitalizations or deaths. Covid-19 wasn’t mild for everyone, but together we are making it through.

While we can’t know for sure what living with this virus will look like in the years to come, we do know that through vaccines, boosters, and infections, members of the MIT community are less susceptible to severe outcomes from Covid-19. We shouldn’t be complacent, but neither should we be fearful. We need to remember that health is much more than simply “not having Covid-19.” It’s about ensuring we all have what we need for our physical and psychological well-being. For many of us, this means starting to spend time with people we haven’t been able to see as much as we’d like, planning vacations and traveling again, returning to activities we enjoyed before the pandemic, and refocusing on friends, families, and loved ones.

Right now, living with Covid-19 doesn’t mean we should drop all precautions. We still need to mask inside campus buildings. We should continue to be careful in crowds. It is still important to be mindful when dining with others indoors. I think about it like a dial, not a switch. There are measures that each of us can take to protect ourselves, to varying degrees, depending upon the conditions around us and what we think our personal risks might be. This is how we can effectively begin living with the reality that Covid-19 will never fully go away.

MIT Medical continues to monitor data in case we need to make future changes in testing protocols and other mitigation strategies. We stand ready to pivot quickly. Omicron may not be the last very transmissible, immune-evading variant we will encounter. Covid-19 might not be our last pandemic. However, MIT has proven that we can successfully navigate these challenges, and we will do so again if necessary.

Q: What role does testing now play, especially as Omicron has been so contagious? How and why is MIT changing its approach to managing the pandemic?

Peko Hosoi: Throughout the pandemic, MIT has focused on implementing the most effective and efficient mitigation strategies at our disposal to control the spread of the virus. We are continuously updating our approach as both the virus and the mitigation landscape evolve. Recall the beginning of the pandemic: We had no vaccines, we were rationing PPE, and we didn’t know much about how the virus was transmitted. Back then, surveillance testing was one of the best (and only!) weapons we had.

Things are very different now. We are a highly vaccinated and boosted community, which makes the risk of severe Covid-19 illness comparable to that of seasonal flu. We have an abundance of KN95 and KF94 masks, which have proven to be extremely effective in limiting the spread of the virus. Our strongest mitigation strategies — masking, vaccination, and boosting — are all individual rather than institutional. And the best testing strategies are shifting in that direction as well.

Testing isn’t going away, and because Omicron spreads so rapidly, adjusting the timing of tests is a much more effective strategy than adjusting testing frequency. For example, suppose my regular testing day is Wednesday, and I go to a gathering on the weekend where I contract Covid-19. By the time I get tested on Wednesday, I will already have been interacting with people on campus for several days during my (unknowingly) most-contagious period. This could be resolved by increasing my testing frequency. But because the Omicron variant is so transmissible, and people become contagious so soon after infection, containing spread by surveillance testing alone (i.e. without other strategies like well-fitted masks) would require testing everyone multiple times every day.

A better approach is to be strategic about when we test. In the example above, where I know I have spent time over the weekend in a situation with an elevated risk of exposure, I should test on Monday rather than waiting until Wednesday. Only you know when your risk level has been elevated, so only you know when you should test. This change in policy doesn’t do away with testing; rather, it shifts the control of test timing to the individual.

A shift from institutional to individual responsibility is, understandably, likely to cause anxiety. Even the most nonchalant members of our community are probably wondering, “Can I trust my neighbor to (individually) do the right thing?” There are two things that may be helpful to remember if that question comes up. First, you are the one with the most control over managing your risk level. If you are concerned about your neighbor’s behavior, you can always take control of the situation by putting on your KN95 or KF94 mask. Second, we have gotten through the past two years with relatively little drama; this was possible because the overwhelming majority of our population did indeed do the right thing.

The past two years have demonstrated very clearly to me that we can trust each other to act responsibly at a time of crisis. That gives me a lot of confidence that we can continue to count on each other to do the right thing as we shift control from the Institute to individual members of our community.

Q: How will policies and protocols evolve in the coming weeks and months? Or, when can the masks come off? When can MIT feel more like MIT again?

Ian Waitz: From the start of the pandemic, we have taken a science-based, many-layered approach that balanced the needs of our campus and surrounding communities. We prioritized flexibility so, as needed, we could ramp up or ramp down preventative measures like masking and testing. And thus far, the approach has worked. Our community’s commitment to keeping themselves and others safe has been incredible.

We’ve had relatively low positive rates and very limited spread on campus, and we successfully adapted during the most challenging phases of the pandemic — like Omicron. Most importantly, we have worked hard to balance a variety of priorities, like the value of in-person learning and working environments, our mental health, and our physical health. It is impossible to get the balance precisely right for everyone at every moment in time because we all have different needs and priorities, which is why we often ask for people to be patient and empathetic toward the needs of others. But overall, I think we have done a good job adjusting as the conditions have changed — sometimes rather quickly as was the case with Omicron. Over the last two years, life on campus has continued to be marked by very low transmission compared to the rest of our lives off campus. Because of the conditions around us, which Cecilia described, we believe that now is the right time to make additional adjustments.

We are now allowing food at events, expanding dining hall seating, allowing faculty to teach unmasked (provided all students are masked), and bringing back fans to our sporting events. In addition, we will reduce required testing to once a week for students, residents, and unvaccinated individuals. Testing for everyone else will become on-demand/as needed. Later, we hope to move everyone to testing on-demand/as needed. Attestation, indoor masking, and 90-day test exemptions for those who have tested positive will remain.

The mandatory campus surveillance testing has been a critically valuable component throughout the pandemic. But as Peko explained, we now must shift our strategy to use it most effectively. We will now be using it in a more targeted way for those who believe they may be infected or have been exposed to the virus. Doing so also marks a shift from MIT being responsible for keeping you safe to you being responsible for keeping you safe. Most of us are incredibly well protected against Covid-19, and those who are most at risk or live with those at higher risk, now have well-understood tools to stay safe.

For those ready to see a prepandemic, unmasked MIT, we would as well! However, we ask for patience. We are not quite ready for that as we are working in a stepwise manner to reduce restrictions and monitor the conditions as we do so. Further, we have to balance our plans with state and local guidance. MIT cannot make rules by fiat, even if we are model citizens with regard to vaccination rates. As for now, the City of Cambridge is firm on keeping masking — a policy we hope will ease up in the coming weeks and months.

Getting over Covid-19 is not going to happen all at once. It is also not going to happen at the same time for each person. We have been through a historic and intense event. Recovery will be a process.

Everyone at MIT has been incredible in the way they have taken care of themselves and one another. Now, more than ever, that is what matters most.