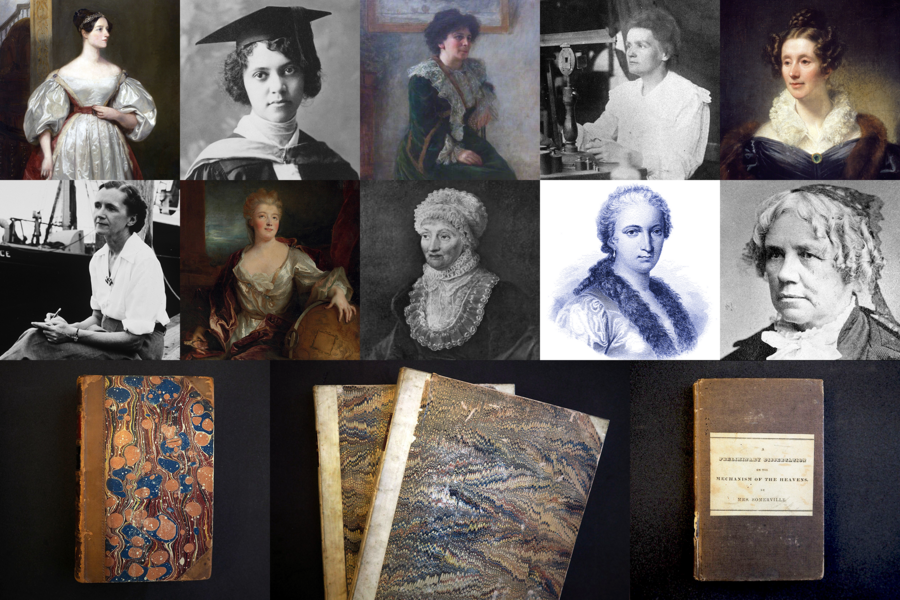

The MIT Libraries maintain a significant collection of rare books featuring works by pioneering scientists, mathematicians, and engineers from the past six centuries. To mark Ada Lovelace Day — an annual celebration of the history of women in the STEM fields — the libraries present a selection of MIT’s holdings by 10 noted women in STEM. The entries herein are inspired by the new Big Names on Campus blog, which highlights important works in STEM history within MIT’s collections. A slideshow below illustrates the variety of documents in the rare collections and in the stacks.

Maria Agnesi

Unlike most 18th-century parents, the mother and father of Italian mathematician Maria Gaetana Agnesi (1718-1799) were not typical for their time: They actively encouraged their daughter to study math and natural philosophy. Agnesi excelled and went on to become the first woman offered a professorship in mathematics at the University of Bologna. Her two-volume “Instituzioni Analitiche” (“Analytical Institutions,” 1748) was translated widely and became a standard university text. MIT owns the original Italian edition as well as the first English translation.

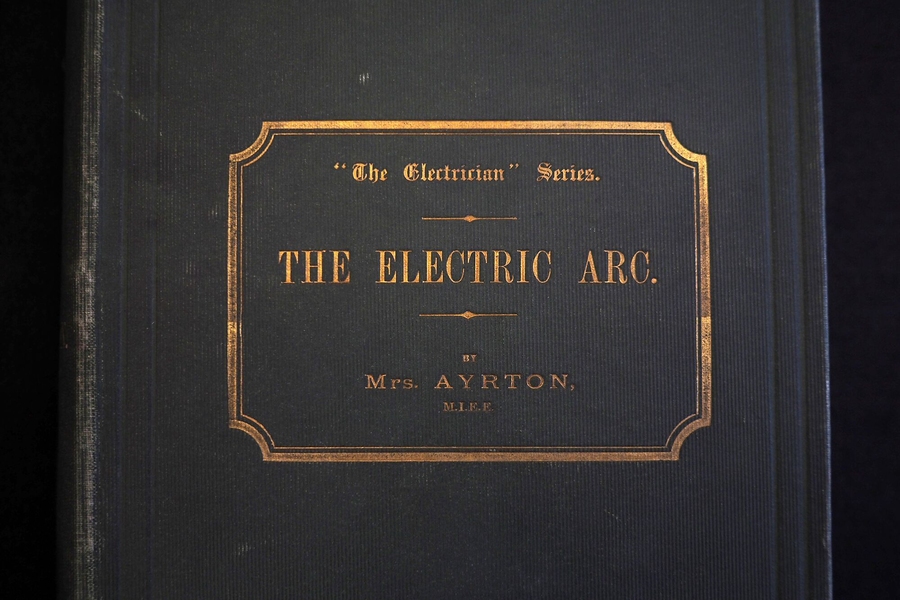

Hertha Ayrton

A British physicist, suffragist, feminist, and the first woman granted membership in the Institution of Electrical Engineers, Hertha Ayrton (1854-1923) wrote the definitive text on electric arcs, a breakdown of gas that creates ongoing electrical discharge. The Royal Society of London awarded her the prestigious Hughes Medal in 1906. MIT owns two copies of Ayrton's "The Electric Arc": One is from the libraries’ historic Vail Collection; the other appeared in the stacks.

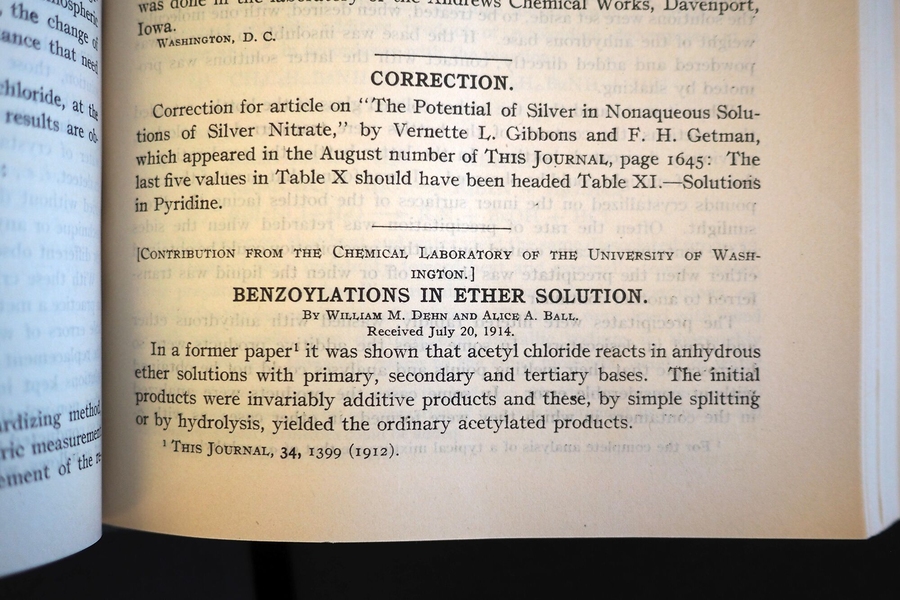

Alice Ball

The life of chemist Alice Ball (1892-1916) was tragically brief, but rich with accomplishment. The first African-American — and the first woman — to receive an advanced degree from the University of Hawaii, she was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society before she even began her graduate studies. Prior to her death at age 24, she devised a treatment that relieved the suffering of thousands with leprosy, a.k.a. Hansen's disease. MIT’s copy of her paper appeared in 1914.

Rachel Carson

American Rachel Carson (1907-1964) trained as a marine biologist and wrote widely on marine matters. But with the publication of “Silent Spring” (1962) — a first edition of which is in MIT’s collections — she became a household name. In response to her argument against unrestrained use of the pesticide DDT, she also became an enemy of the pesticide industry, even though a scientific advisory panel headed by MIT's Jerome Wiesner supported her findings. Carson's science withstood attacks, and the book was a sensation, giving rise to the modern ecology movement.

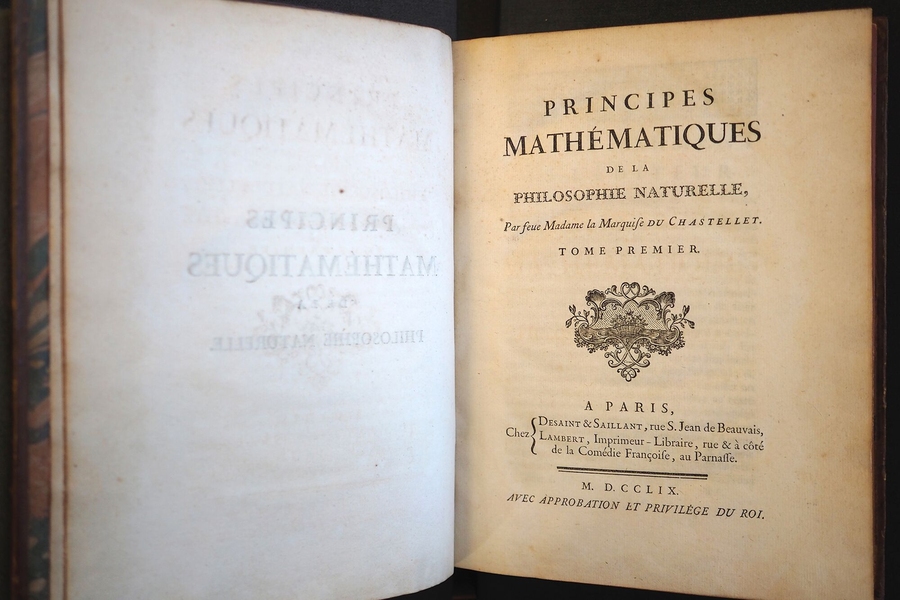

Émilie du Châtelet

Raised amid the court of Louis XIV, French scholar Émilie du Châtelet (1706-1749) was bred to be an ornament of society. Her charm and wit were indeed celebrated, but she made her real mark among the French intelligentsia. She wrote on physics and championed Isaac Newton before unreceptive Parisian academics. Her French translation of his “Principia” — and, more significantly, her in-depth commentary upon it — has never been supplanted. When the MIT Libraries established its first fund for rare book acquisitions in 2015, this was the initial purchase.

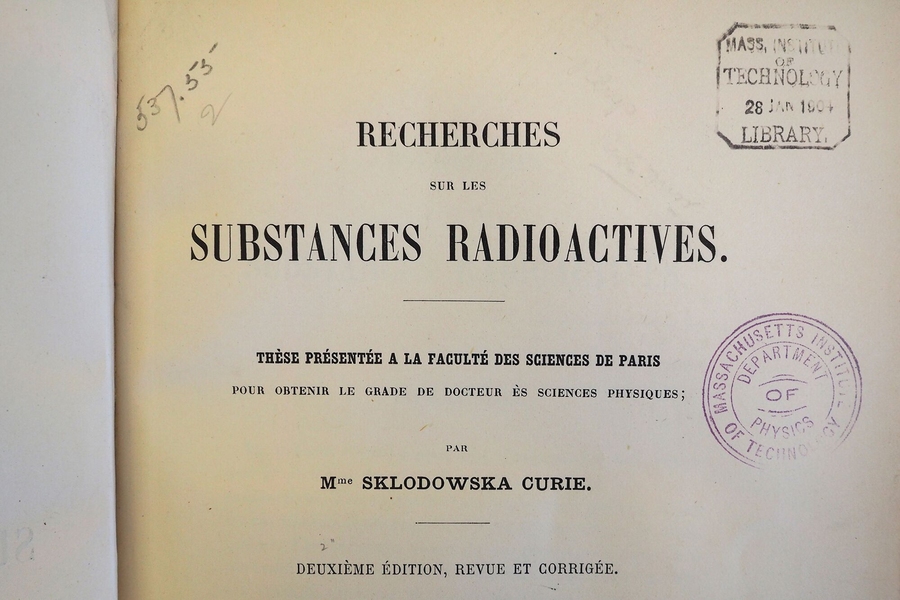

Marie Curie

Only four people have ever won the Nobel Prize twice, and the first to do it was Polish-French scientist Marie Curie (1867-1934). The 1903 physics prize was shared by Curie, her husband Pierre, and Henri Becquerel for their work on radiation. In 1911 Curie won the chemistry prize outright for her discovery of the elements radium and polonium. Her doctoral thesis (1903) was published commercially and translated widely; MIT owns copies in several languages.

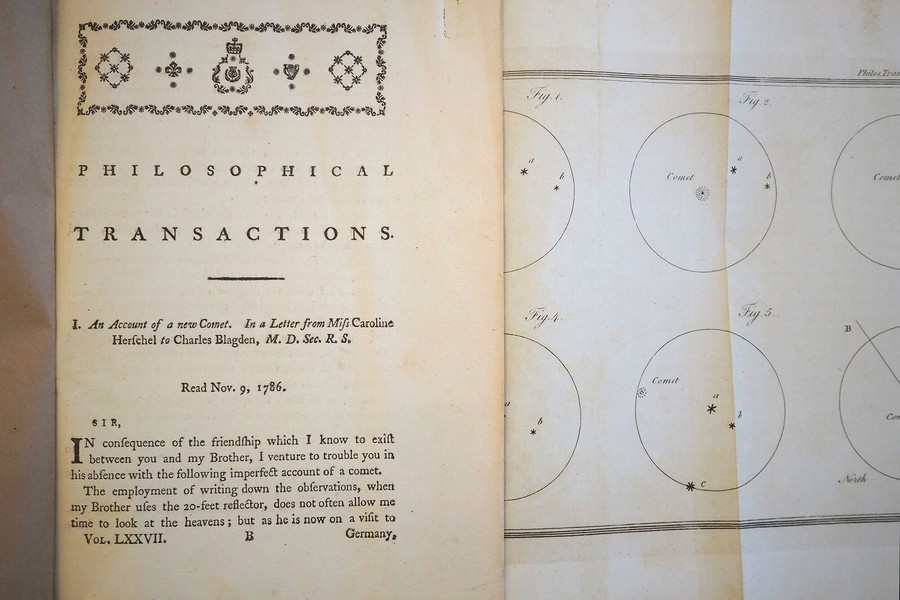

Caroline Herschel

Caroline Herschel (1750-1848) received a minimal education and was treated as a housemaid by her parents in Germany. When she was 22, she traveled to England to join her brother, astronomer William Herschel, hoping for a career in music. Instead, she ended up assisting her brother, often performing menial tasks. Eventually though, she took to astronomy herself, discovering three nebulae and eight comets. Among other honors, the Royal Astronomical Society awarded Herschel its Gold Medal in 1828. MIT’s copy of a 1786 report on one of her comet discoveries includes a pullout with engravings of her observations.

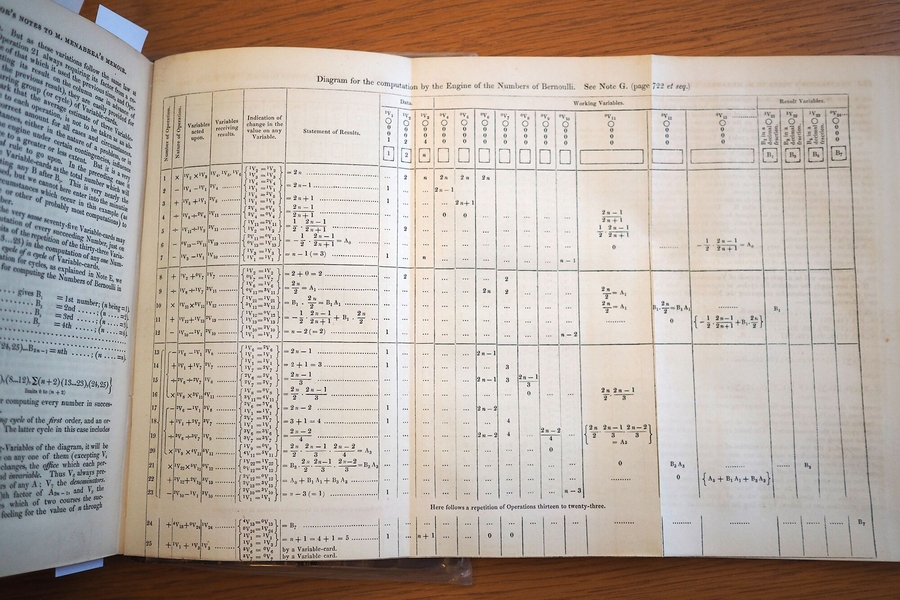

Ada Lovelace

The creators of Ada, a programming language developed for the U.S. Department of Defense in the early 1980s, had good reasons for naming it after British mathematician Ada Lovelace (1815-1852). Like her, it's highly sophisticated and accomplishes a great deal. In 1843, Lovelace set out to translate a French article describing Charles Babbage's proposed "Analytical Engine," an early computing machine. She took matters much further, and when the translation was published with her extensive additions, the world had been presented with what many consider the first computer program. MIT owns an original copy of the translation, which includes her groundbreaking description of how the Analytical Engine would compute the Bernoulli number sequence.

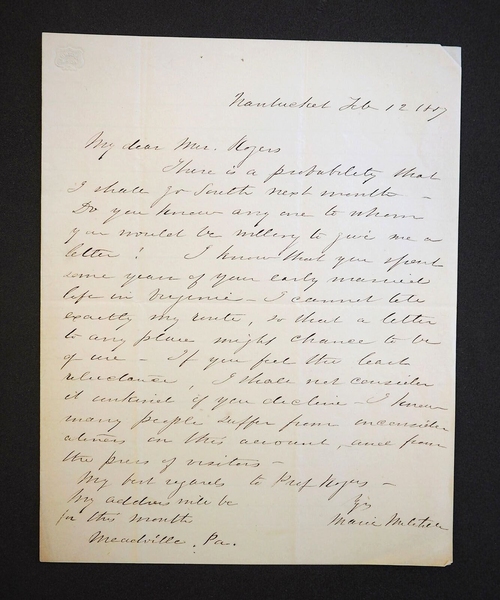

Maria Mitchell

Massachusetts-born Maria Mitchell (1818-1889) was America's first professional female astronomer. Mitchell held several overlapping jobs: She was the Nantucket Atheneum's librarian; she computed ephemerides for the U.S. Nautical Almanac; and she was on the faculty of Vassar College from its inception. The first woman to earn membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Mitchell also received a gold medal from Frederick VI of Denmark for her discovery of a comet in 1847. Within MIT’s holdings is a hand-written letter from Mitchell to Emma Rogers, wife of MIT founder William Barton Rogers.

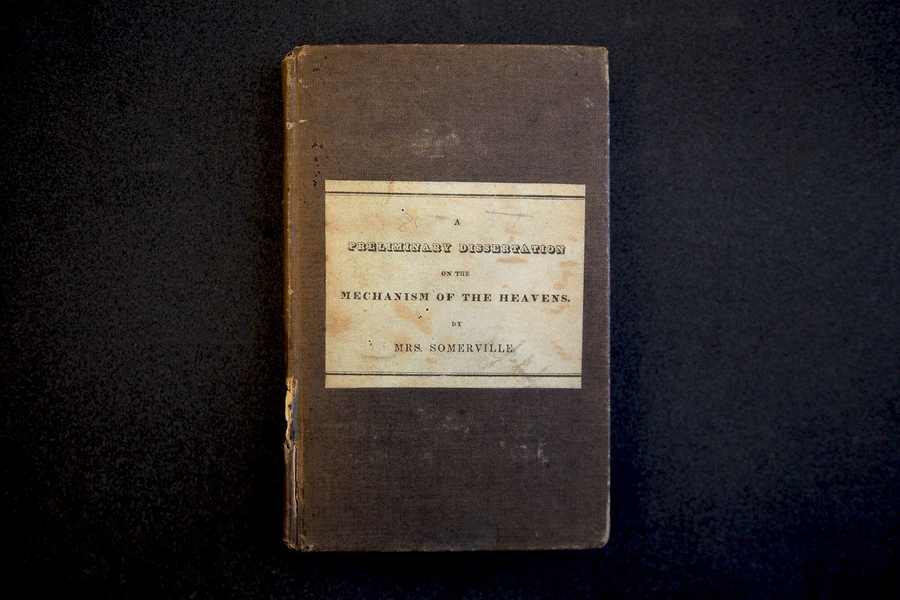

Mary Somerville

Like Émilie du Châtelet and Ada Lovelace, Scottish writer Mary Somerville (1780-1872) set out to do a translation and ended up creating original work that remains influential. Her first book was “Mechanism of the Heavens” (1831), a "common language" translation of Pierre-Simon Laplace's “Traité de Mécanique Céleste” that was swiftly adopted as a university textbook. Her “Preliminary Dissertation,” the book's preface, was so well-regarded that it was published separately as an introductory astronomy text — and MIT holds a copy of this publication from 1832. These and other important works were produced by a woman whose father had forbidden her from reading his books.