The following is adapted from an announcement today by Fermilab.

Scientists looking for dark matter face a serious challenge: No one knows what dark matter particles look like. So their search covers a wide range of possible traits — different masses, different probabilities of interacting with regular matter.

Today, scientists on the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search experiment, or CDMS, announced that they have shifted the border of this search down to a dark-matter particle mass and rate of interaction that has never been probed.

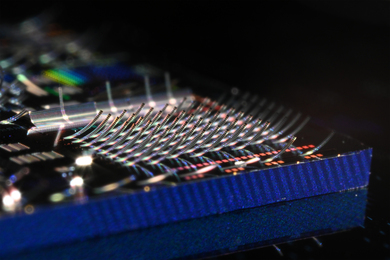

The analysis, led by Adam Anderson, an MIT graduate student in physics, is the first dark matter result using a new sensor technology — developed, in part, at MIT — that shows much better rejection of background events than the previous generation of CDMS detectors. The work was presented today at the Symposium on Sources and Detection of Dark Matter and Dark Energy in the Universe, held at the University of California at Los Angeles.

“We’re pushing CDMS to as low mass as we can,” says Fermilab physicist Dan Bauer, the project manager for CDMS. “We’re proving the particle detector technology here.”

The result, which does not claim any hints of dark matter particles, contradicts a result announced in January by another dark matter experiment, CoGeNT, which uses particle detectors made of germanium, the same material as used by CDMS.

To search for dark matter, CDMS scientists cool their detectors to very low temperatures in order to detect the very small energies deposited by the collisions of dark matter particles with the germanium. They operate their detectors half a mile underground in a former iron ore mine in northern Minnesota. The mine provides shielding from cosmic rays that could clutter the detector as it waits for passing dark matter particles.

Today’s result carves out interesting new dark matter territory for masses below 6 gigaelectronvolts (GeV). The dark matter experiment Large Underground Xenon, or LUX, recently ruled out a wide range of masses and interaction rates above that with the announcement of its first result last October.

Scientists have expressed increasing interest in the search for low-mass dark matter particles, with CDMS and three other experiments — DAMA, CoGeNT, and CRESST — all finding their data compatible with the existence of dark matter particles between 5 and 20 GeV. But such light dark-matter particles are hard to pin down. The lower the mass of the dark-matter particles, the less energy they leave in detectors, and the more likely it is that background noise will drown out any signals.

Even more confounding is the fact that scientists don’t know whether dark matter particles interact in the same way in detectors built with different materials. In addition to germanium, scientists use argon, xenon, silicon, and other materials to search for dark matter in more than a dozen experiments around the world.

“It’s important to look in as many materials as possible to try to understand whether dark matter interacts in this more complicated way,” says Anderson, who worked on the latest CDMS analysis as part of his MIT thesis. “Some materials might have very weak interactions. If you only picked one, you might miss it.”

Scientists around the world seem to be taking that advice, building different types of detectors and constantly improving their methods.

“Progress is extremely fast,” Anderson says. “The sensitivity of these experiments is increasing by an order of magnitude every few years.”

Scientists looking for dark matter face a serious challenge: No one knows what dark matter particles look like. So their search covers a wide range of possible traits — different masses, different probabilities of interacting with regular matter.

Today, scientists on the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search experiment, or CDMS, announced that they have shifted the border of this search down to a dark-matter particle mass and rate of interaction that has never been probed.

The analysis, led by Adam Anderson, an MIT graduate student in physics, is the first dark matter result using a new sensor technology — developed, in part, at MIT — that shows much better rejection of background events than the previous generation of CDMS detectors. The work was presented today at the Symposium on Sources and Detection of Dark Matter and Dark Energy in the Universe, held at the University of California at Los Angeles.

“We’re pushing CDMS to as low mass as we can,” says Fermilab physicist Dan Bauer, the project manager for CDMS. “We’re proving the particle detector technology here.”

The result, which does not claim any hints of dark matter particles, contradicts a result announced in January by another dark matter experiment, CoGeNT, which uses particle detectors made of germanium, the same material as used by CDMS.

To search for dark matter, CDMS scientists cool their detectors to very low temperatures in order to detect the very small energies deposited by the collisions of dark matter particles with the germanium. They operate their detectors half a mile underground in a former iron ore mine in northern Minnesota. The mine provides shielding from cosmic rays that could clutter the detector as it waits for passing dark matter particles.

Today’s result carves out interesting new dark matter territory for masses below 6 gigaelectronvolts (GeV). The dark matter experiment Large Underground Xenon, or LUX, recently ruled out a wide range of masses and interaction rates above that with the announcement of its first result last October.

Scientists have expressed increasing interest in the search for low-mass dark matter particles, with CDMS and three other experiments — DAMA, CoGeNT, and CRESST — all finding their data compatible with the existence of dark matter particles between 5 and 20 GeV. But such light dark-matter particles are hard to pin down. The lower the mass of the dark-matter particles, the less energy they leave in detectors, and the more likely it is that background noise will drown out any signals.

Even more confounding is the fact that scientists don’t know whether dark matter particles interact in the same way in detectors built with different materials. In addition to germanium, scientists use argon, xenon, silicon, and other materials to search for dark matter in more than a dozen experiments around the world.

“It’s important to look in as many materials as possible to try to understand whether dark matter interacts in this more complicated way,” says Anderson, who worked on the latest CDMS analysis as part of his MIT thesis. “Some materials might have very weak interactions. If you only picked one, you might miss it.”

Scientists around the world seem to be taking that advice, building different types of detectors and constantly improving their methods.

“Progress is extremely fast,” Anderson says. “The sensitivity of these experiments is increasing by an order of magnitude every few years.”