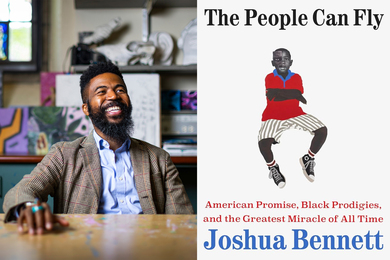

Arthur R. von Hippel embodied scientific curiosity and mentorship and shared her passion for music, MIT Institute Professor Emeritus Mildred S. Dresselhaus said Wednesday night in accepting the Materials Research Society award named in his honor.

The Materials Research Society has conferred the MRS Von Hippel Award annually since 1976, when it was given to von Hippel. Dresselhaus received the award for her pioneering contributions to the fundamental science of carbon-based and other low-electron-density materials, her leadership in energy and science policy, and her exemplary mentoring of young scientists.

Von Hippel encouraged Dresselhaus, made her part of his string quartet, and remained her friend from the time she joined MIT’s Lincoln Lab in 1960 until his death in 2003 at 105. Dresselhaus became a professor at MIT in 1968.

Dresselhaus said she had good luck in finding mentors over her long career: future Nobel Laureate Rosalyn Yalow, while Dresselhaus was an undergraduate at Hunter College in New York; Enrico Fermi, while she was a graduate student at the University of Chicago; and von Hippel at MIT. (Dresselhaus received the Enrico Fermi award from President Barack Obama in 2012.)

Dresselhaus was encouraged to “work on something that was interesting to me and that people didn’t know anything about,” she said. “That was the 1960s. Carbon science had essentially nobody working in there, so von Hippel thought that was a pretty good topic to be working on.” He encouraged her to work on graphite, a simple form of carbon.

“The carbon-carbon bond is the strongest bond in nature,” Dresselhaus said. “We wouldn’t have a space industry without the carbon-carbon bond.”

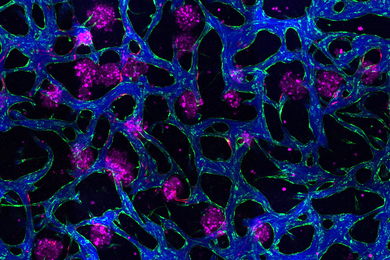

Dresselhaus’s work led her to perform experiments with circularly polarized light from a helium-neon laser — a new technology in the 1960s — that established the location of electrons and holes, or electron vacancies, in graphite. She went on to study superconductivity in layered carbon and potassium compounds, and then fullerenes and carbon nanotubes, writing books on the latter two. At the prompting of government researchers, she wrote “Graphite Fibers and Filaments.” “We became experts in carbon fibers for a while,” she said.

In later spectroscopy experiments, Dresselhaus and colleagues showed that carbon nanotubes could be either metallic or semiconducting. “Nanoscience has really benefited from all those ideas,” she said.

Dresselhaus recalled that von Hippel, who worked in the lab until age 90, helped develop radar during World War II and was always interested in practical applications as well as theoretical research. “He liked complicated materials and was an expert in perovskites and ferroelectrics,” she said.

In answer to a question about women in science, Dresselhaus encouraged current faculty to be active mentors — as von Hippel was to her — and particularly to encourage young women to become scientists. Even before college, many young women are discouraged, she said, with questions such as “What is a pretty girl like you doing studying physics?” Faculty need to encourage young women to be successful in both their personal and their professional lives, and they can help by sharing their own personal quests to achieve balance, she said.

Materials Research Society President Orlando Auciello, of the University of Texas at Dallas, presented the award to Dresselhaus at the Grand Ballroom of the Sheraton Boston Hotel. The award includes a $10,000 cash prize.

The Materials Research Society has conferred the MRS Von Hippel Award annually since 1976, when it was given to von Hippel. Dresselhaus received the award for her pioneering contributions to the fundamental science of carbon-based and other low-electron-density materials, her leadership in energy and science policy, and her exemplary mentoring of young scientists.

Von Hippel encouraged Dresselhaus, made her part of his string quartet, and remained her friend from the time she joined MIT’s Lincoln Lab in 1960 until his death in 2003 at 105. Dresselhaus became a professor at MIT in 1968.

Dresselhaus said she had good luck in finding mentors over her long career: future Nobel Laureate Rosalyn Yalow, while Dresselhaus was an undergraduate at Hunter College in New York; Enrico Fermi, while she was a graduate student at the University of Chicago; and von Hippel at MIT. (Dresselhaus received the Enrico Fermi award from President Barack Obama in 2012.)

Dresselhaus was encouraged to “work on something that was interesting to me and that people didn’t know anything about,” she said. “That was the 1960s. Carbon science had essentially nobody working in there, so von Hippel thought that was a pretty good topic to be working on.” He encouraged her to work on graphite, a simple form of carbon.

“The carbon-carbon bond is the strongest bond in nature,” Dresselhaus said. “We wouldn’t have a space industry without the carbon-carbon bond.”

Dresselhaus’s work led her to perform experiments with circularly polarized light from a helium-neon laser — a new technology in the 1960s — that established the location of electrons and holes, or electron vacancies, in graphite. She went on to study superconductivity in layered carbon and potassium compounds, and then fullerenes and carbon nanotubes, writing books on the latter two. At the prompting of government researchers, she wrote “Graphite Fibers and Filaments.” “We became experts in carbon fibers for a while,” she said.

In later spectroscopy experiments, Dresselhaus and colleagues showed that carbon nanotubes could be either metallic or semiconducting. “Nanoscience has really benefited from all those ideas,” she said.

Dresselhaus recalled that von Hippel, who worked in the lab until age 90, helped develop radar during World War II and was always interested in practical applications as well as theoretical research. “He liked complicated materials and was an expert in perovskites and ferroelectrics,” she said.

In answer to a question about women in science, Dresselhaus encouraged current faculty to be active mentors — as von Hippel was to her — and particularly to encourage young women to become scientists. Even before college, many young women are discouraged, she said, with questions such as “What is a pretty girl like you doing studying physics?” Faculty need to encourage young women to be successful in both their personal and their professional lives, and they can help by sharing their own personal quests to achieve balance, she said.

Materials Research Society President Orlando Auciello, of the University of Texas at Dallas, presented the award to Dresselhaus at the Grand Ballroom of the Sheraton Boston Hotel. The award includes a $10,000 cash prize.