A live video feed from the International Space Station and a deep-sea radio transmission from near the site of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill established broad parameters for a two-day symposium at MIT examining the new world of exploration.

The event, which took place April 26-27, was the penultimate in a series of six symposia to mark MIT’s 150th anniversary. Explorers both Earth-bound and beyond gathered at Kresge Auditorium to honor human achievements in exploration and the technologies that have made extreme expeditions possible, including deep-sea diving robots, zero-gravity flights, lunar spacecraft and the Mars rovers.

“We’re here to celebrate the human experience, and what it means for humans to be here,” said symposium chair Dava Newman SM ’89, PhD ’92, professor of aeronautics and astronautics and engineering systems. Newman opened the symposium by asking the many students in the audience to stand.

“This is for you,” she said. “You really are the future of exploration.”

Astronaut Catherine “Cady” Coleman ’83, who joined the symposium via satellite link from the International Space Station (ISS), gave the audience a view of Earth from the windows of the ISS, saying, “It’s not a question of if MIT students will be on the International Space Station. It’s a question of which [student].”

Exploring exploration

The symposium began with a look back at the history of exploration, from early expeditions to map the seas through the discovery of the continents. Stephen Pyne, an author and biologist from Arizona State University, pointed to science as a major driver in changing the profile of exploration during the 18th century. “The missionary drops out of the picture as an active explorer, replaced by the natural scientist,” Pyne said.

The discovery of Earth’s last continental boundaries capped off a golden age of land exploration, while ushering in a new era of space travel, robotic technology and computer programming. David Mindell PhD ’96, the Frances and David Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing and chair of the MIT150 Steering Committee, credited software engineers as explorers in their own right, working with data from underwater vehicles and orbiting satellites that are “buzzing away, carrying all our human intentions.”

Rosalind Williams, the Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Science and Technology, said exploration throughout history has always been a very human endeavor, no matter the technology involved in getting there. “Explorers have always come back from the edge to report back to the human world,” Williams said.

Back from the edge

And several of the most extreme explorers in history were on hand at the symposium: One panel featured Apollo 11’s Buzz Aldrin ScD ’63, and seven other MIT alumni who are former U.S. astronauts. Michael Massimino SM ’88, MEng ’90, PhD ’92, recalled one spacewalk when he had a moment to simply look back at the Earth, unobstructed.

“I could hardly stand to look at it, it was so beautiful,” Massimino said. The sight made the astronaut momentarily tear up, which immediately made him nervous: The tears could have caused water buildup in his spacesuit, leading to an official NASA investigation.

“I’d have to admit that I was crying,” Massimino said.

Looking forward, the astronauts identified Mars as the next frontier, with Aldrin encouraging scientists to build depots and stations on the red planet to “establish permanence” and explore martian resources. Jeff Greason, founder and CEO of XCOR Aerospace, echoed Aldrin, saying, “We have to start making economic use of our space exploration.”

Throughout the symposium, researchers at MIT outlined work in exploring resources in space, from investigations of meteorites for metals and microbes to the study of lunar gravity to the search for water on Mars and the hunt for planets in deep space.

The deep end

Searching for resources has also been a focus in “blue space,” as oceanographers described the world of ocean exploration. James Bellingham SB ’84, SM ’84, PhD ’88, chief technologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, said microbes are the key mysteries in ocean exploration. “Every drop of ocean is a living community, literally transforming the chemistry of the ocean every second,” Bellingham said.

Dana Yoerger SB ’77, SM ’79, PhD ’83, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), phoned in to the symposium from the Gulf of Mexico, where he is using autonomous underwater vehicles to map the plume from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Yoerger said the future of ocean exploration will be driven in part by smarter deep-sea vehicles that can semi-autonomously explore hydrothermal vents, identify ship wreckage and track human impacts in the ocean.

Susan Humphris PhD ’77, senior scientist at WHOI, added that a network of smart robots could help scientists understand earthquake activity on the sea floor, particularly along the Pacific Ocean’s so-called “Ring of Fire.” Such a “networked ocean” may be able to detect early signals of an earthquake and issue alerts well in advance.

Back to the future

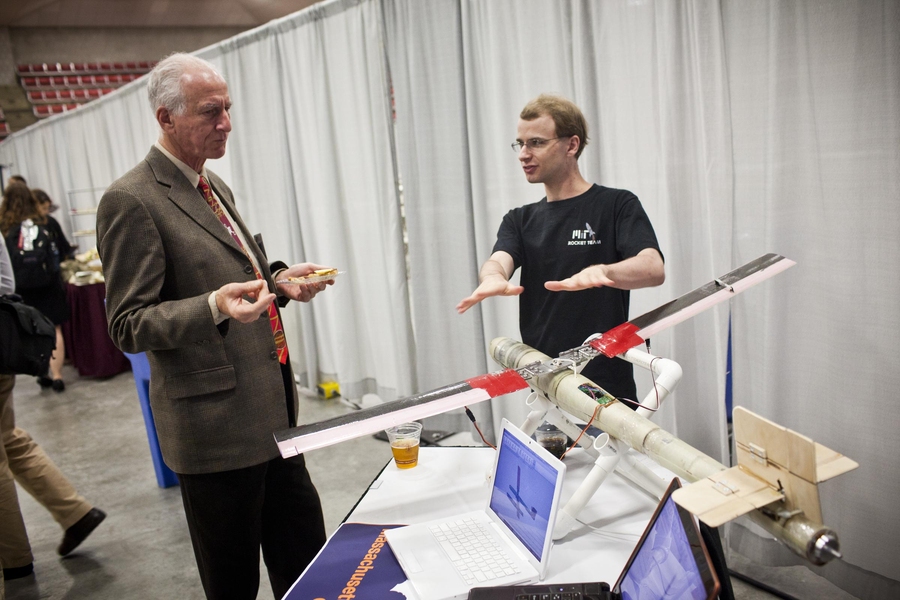

Attendees of the symposium got a glimpse of the future of exploration at an exhibit featuring projects by MIT students and faculty, including a next-generation spacesuit, planetary hoppers, a solar-powered car, and the first practical flying car.

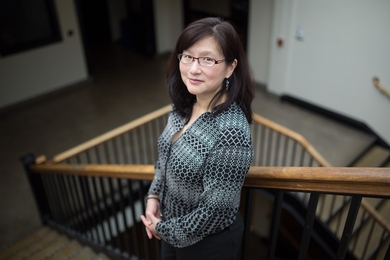

The symposium also included presentations from finalists of the XCOR Student Showcase Competition, a contest designed specifically for the symposium to generate innovative ideas for future exploration. The winning concept was a constellation of small satellites to track exoplanets in deep space, a system that senior Mary Knapp said would “clear away the dust” and provide a clearer picture of far-out galaxies.

Peter Diamandis SB ’83, SM ’88, chairman and CEO of the X PRIZE Foundation, says competitions like the one sponsored by XCOR can be “transformative” in stimulating small groups toward big goals in exploration. Diamandis outlined his incredibly steep trajectory in establishing the X PRIZE, which sponsors competitions to “bring about radical breakthroughs” in science.

“You will be told ‘no’ over and over again,” Diamandis told students. “But you have to do something that gives you meaning … when you find that, no one can stop you.”

From deep space to deep sea, two-day symposium examined MIT’s impacts and innovations.

Publication Date:

Caption:

David Mindell, right, the Frances and David Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing, speaks about the history of exploration. Stephen J. Pyne, Regents’ professor at Arizona State University, and Rosalind Williams, Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Science and Technology, look on.

Credits:

Photo: Dominick Reuter

Caption:

MIT senior Mary Knapp presents a prototype of a small satellite at the XCOR Student Showcase Competition. Knapp won first place for her concept, SOLARA, a constellation of small satellites that track exoplanets in deep space.

Credits:

Photo: Dominick Reuter

Caption:

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin ScD ’63 signs his autograph for a fan.

Credits:

Photo: Dominick Reuter

Caption:

Astronaut Catherine 'Cady' Coleman ’83 addresses the audience from the International Space Station.

Credits:

Photo: Dominick Reuter

Caption:

The first practical flying car, developed by MIT alumni, was on display at the MIT150 Symposium on Exploration, along with other MIT-derived high-concept vehicles.

Credits:

Photo: Dominick Reuter

Caption:

Jeffrey Hoffman, Professor of the Practice of Aerospace Engineering, gets up to speed on the latest designs by the MIT Rocket Team.

Credits:

Photo: Dominick Reuter