After receiving chemotherapy, many cancer patients go into a remission that can last months or years. But in some of those cases, tumors eventually grow back, and when they do, they are frequently resistant to the drugs that initially worked.

Now, in a study of mice with lymphoma, MIT biologists have discovered that a small number of cancer cells escape chemotherapy by hiding out in the thymus, an organ where immune cells mature. Within the thymus, the cancer cells are bathed in growth factors that protect them from the drugs’ effects. Those cells are likely the source of relapsed tumors, said Michael Hemann, MIT assistant professor of biology, who led the study.

The researchers plan to soon begin tests, in mice, of drugs that interfere with one of those protective factors. Those drugs were originally developed to treat arthritis, and are now in clinical trials for that use. Such a drug, used in combination with traditional chemotherapy, could offer a one-two punch that eliminates residual tumor cells and prevents cancer relapse, according to the researchers.

“Successful cancer therapy needs to involve a component that kills tumor cells as well as a component that blocks pro-survival signals,” said Hemann, who is a member of MIT’s David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. “Current cancer therapies fail to target this survival response.”

Hemann and graduate student Luke Gilbert described the findings in the Oct. 29 issue of the journal Cell.

Stress response

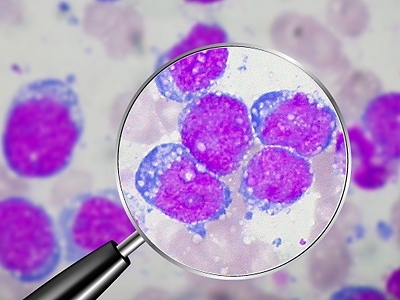

In the new study, the researchers treated mice with lymphoma with doxorubicin, a drug commonly used to treat a wide range of cancers, including blood cancers. They found that during treatment, cells that line the blood vessels release cytokines — small proteins that influence immune responses and cell development.

The exact mechanism is not known, but the researchers believe that chemotherapy-induced DNA damage provokes those blood-vessel cells to launch a stress response that is normally intended to protect progenitor cells — immature cells that can become different types of blood cells. That stress response includes the release of cytokines such as interleukin-6, which promotes cell survival.

“In response to environmental stress, the hardwired response is to protect privileged cells in that area, i.e., progenitor cells,” said Hemann. “These pathways are being coopted by tumor cells, in response to the frontline cancer therapies that we use.”

The discovery marks the first time scientists have seen a protective signal evoked by chemotherapy in the area surrounding the tumor, known as the tumor microenvironment. “It’s completely unexpected that drugs would promote a survival response,” said Hemann. “The impact of local survival factors is generally not considered when administering chemotherapy, let alone the idea that frontline chemotherapy would induce pro-survival signals.”

“It’s a very interesting model for drug resistance — different from the way people have been thinking about this,” said David Straus, a physician who specializes in treating lymphoma at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Straus, who was not involved in the study, said it remains to be seen if the results will translate to human patients, but the finding does suggest several potential drug targets, including IL-6 and a protein called Bcl2, which is activated by IL-6 and signals cells to stay alive.

While the MIT researchers observed this protective effect only in the thymus, they believe there may be other protected areas where tumor cells hide, such as the bone marrow.

This finding could help explain why tumors that have spread to other parts of the body before detection are more resistant to frontline chemotherapy: They may have already engaged a protective cytokine system, helping them to survive the drugs’ effects.

Hemann hopes to further clarify the mechanism in future studies, in collaboration with Professor Michael Yaffe, also a member of the Koch Institute. He also plans to investigate whether this kind of pro-survival signal is elicited in other types of cancer, including tumors that have metastasized.

Now, in a study of mice with lymphoma, MIT biologists have discovered that a small number of cancer cells escape chemotherapy by hiding out in the thymus, an organ where immune cells mature. Within the thymus, the cancer cells are bathed in growth factors that protect them from the drugs’ effects. Those cells are likely the source of relapsed tumors, said Michael Hemann, MIT assistant professor of biology, who led the study.

The researchers plan to soon begin tests, in mice, of drugs that interfere with one of those protective factors. Those drugs were originally developed to treat arthritis, and are now in clinical trials for that use. Such a drug, used in combination with traditional chemotherapy, could offer a one-two punch that eliminates residual tumor cells and prevents cancer relapse, according to the researchers.

“Successful cancer therapy needs to involve a component that kills tumor cells as well as a component that blocks pro-survival signals,” said Hemann, who is a member of MIT’s David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. “Current cancer therapies fail to target this survival response.”

Hemann and graduate student Luke Gilbert described the findings in the Oct. 29 issue of the journal Cell.

Stress response

In the new study, the researchers treated mice with lymphoma with doxorubicin, a drug commonly used to treat a wide range of cancers, including blood cancers. They found that during treatment, cells that line the blood vessels release cytokines — small proteins that influence immune responses and cell development.

The exact mechanism is not known, but the researchers believe that chemotherapy-induced DNA damage provokes those blood-vessel cells to launch a stress response that is normally intended to protect progenitor cells — immature cells that can become different types of blood cells. That stress response includes the release of cytokines such as interleukin-6, which promotes cell survival.

“In response to environmental stress, the hardwired response is to protect privileged cells in that area, i.e., progenitor cells,” said Hemann. “These pathways are being coopted by tumor cells, in response to the frontline cancer therapies that we use.”

The discovery marks the first time scientists have seen a protective signal evoked by chemotherapy in the area surrounding the tumor, known as the tumor microenvironment. “It’s completely unexpected that drugs would promote a survival response,” said Hemann. “The impact of local survival factors is generally not considered when administering chemotherapy, let alone the idea that frontline chemotherapy would induce pro-survival signals.”

“It’s a very interesting model for drug resistance — different from the way people have been thinking about this,” said David Straus, a physician who specializes in treating lymphoma at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Straus, who was not involved in the study, said it remains to be seen if the results will translate to human patients, but the finding does suggest several potential drug targets, including IL-6 and a protein called Bcl2, which is activated by IL-6 and signals cells to stay alive.

While the MIT researchers observed this protective effect only in the thymus, they believe there may be other protected areas where tumor cells hide, such as the bone marrow.

This finding could help explain why tumors that have spread to other parts of the body before detection are more resistant to frontline chemotherapy: They may have already engaged a protective cytokine system, helping them to survive the drugs’ effects.

Hemann hopes to further clarify the mechanism in future studies, in collaboration with Professor Michael Yaffe, also a member of the Koch Institute. He also plans to investigate whether this kind of pro-survival signal is elicited in other types of cancer, including tumors that have metastasized.