Mexico’s president Felipe Calderon has made a military campaign against the country’s ascendant drug-trafficking gangs the centerpiece of his presidency. After thousands of fatalities, many of them due to retaliatory strikes by the cartels — including the murders of United States consulate workers last month — the battle remains unresolved.

“I don’t see the drug traffickers giving up, and I don’t see the Mexican government winning this struggle with violence,” says Diane Davis, a professor of political sociology in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, and a leading scholar of society and politics in Mexico.

Lately, Davis and other similarly minded experts have been making an increasingly public case that the Mexican government will not find long-term success focusing on a conventional military-style battle, as if it were fighting conventional insurgents from Latin America’s past, such as Colombia’s rural rebels. That is because, Davis argues in a pair of recent scholarly articles, Mexico’s cartels constitute “irregular armed forces” — well-organized, flexible urban gangs that make money smuggling drugs and other goods — buttressed by Mexico’s socioeconomic problems.

The cartels, Davis contends, are different from rebel groups: They aim not to remove the whole government, but instead to usurp some of its functions. “Their activities are not always motivated by anti-government ideals or regime change,” Davis states in a new article, “Irregular Armed Forces, Shifting Patterns of Commitment, and Fragmented Sovereignty in the Developing World,” published in the March issue of Theory and Society. Rather, the cartels use violence to protect their “clandestine networks of capital accumulation.”

By consensus of analysts, Mexican cartels now operate the most lucrative drug-smuggling routes into the Unites States, which had been under the control of Colombian groups in the 1980s and 1990s. The Mexican cartels now bring in from $10 billion to $25 billion annually from smuggling, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal this month.

In classic sociological theory, the state has a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence through military and police forces. But in Mexico, drug cartels challenge that monopoly, and more brazenly than ever. “Think of the armed forces linked to drug lords as a form of a ‘privatized army,’” says Davis.

The smuggling revenues of the cartels also give them staying power. “In cities, these groups have economic networks to supply the money to fight,” Says Davis. The resulting violence has reached levels that “resemble body counts from civil war battles,” as Davis writes. In the first half of 2009, Mexico saw an average of 127 cartel-related killings per week.

Narco-gang offer: ‘good salary, food, and help for families’

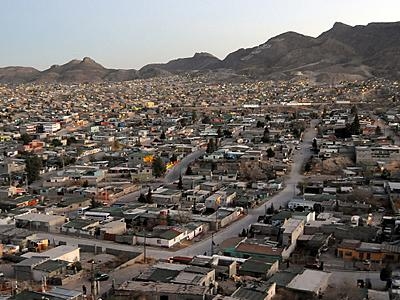

In Davis’ view, the massive urbanization of Mexico — more than 70 percent of Mexicans live in cities now, compared to about half in 1960 — has created social dislocations the cartels exploit. About 70 percent of Mexico’s urban labor force works in the “informal sector” of the economy, in transient jobs for small firms or in the world of black-market commerce. “As a result,” Davis writes, “much informal employment is physically and socially situated within an illicit commercial world” beyond the reach of the state, where violence occurs as gangs try to control drug supply routes. Moreover, informal workers are often not eligible for government safety-net benefits, making them even less invested in the success of the state.

Thus the cartels have been startlingly open about recruiting new members. In the city of Laredo in 2008, Davis notes, a drug gang called the Zetas hung a banner on a downtown bridge asking for “military recruits and ex-military men … seeking a good salary, food, and help for their families,” with a phone number posted for prospective enlistees. Other gangs were founded outside Mexico, but have spread inside the country: one such group, los Maras, was founded by “city-based youth who turned to criminal activity because of the lack of employment alternatives in the large metropolitan areas of California, Mexico, and Central America,” Davis writes in another article, “Non-State Armed Actors, New Imagined Communities, and Shifting Patterns of Sovereignty and Insecurity in the Modern World,” published in the August 2009 issue of Contemporary Security Policy. (In February, the article received the Bernard Brodie Prize, awarded to the best article appearing in Contemporary Security Policy each year.)

Mexico’s drug wars thus involve physically dispersed, evolving organizations that could be viewed more as self-sustaining networks than anti-state insurgents. “I think we still need to develop our analysis to better understand what’s going on in Mexico, and that’s why Davis’ contribution is so relevant,” states Fabio Armao, a professor of international relations at the University of Turin who studies organized crime.

A real long-term solution to Mexico’s problems, Davis notes, will require economic development, to lessen the influence of the drug trade and reduce the appeal of gang recruitment efforts. Such long-term economic changes have happened before: As The Wall Street Journal report stated, the cocaine industry has shrunk from an estimated 6 percent of Colombia economy in 1987 to under 1 percent today. Yet as The New York Times noted in March, of the more than $1 billion the United States has provided Mexico during the last two administrations, much has been for military and police equipment and training.

As Davis sees it, the Mexican government may be better equipped in the short run, but it still lacks a long-term perspective. And of the outlook in Washington, Davis says, “Attention is finally turning to Latin America, but the economic and policy contours have yet to be seen.” Among other things, Davis believes, the United States must work to limit its demand for drugs smuggled through Mexico. “I think some responsibility has to be accepted, and some re-thinking about trade and other incentives to get at the root of these transnational smuggling networks has got to be on the agenda. It is time for a paradigm shift.”

“I don’t see the drug traffickers giving up, and I don’t see the Mexican government winning this struggle with violence,” says Diane Davis, a professor of political sociology in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, and a leading scholar of society and politics in Mexico.

Lately, Davis and other similarly minded experts have been making an increasingly public case that the Mexican government will not find long-term success focusing on a conventional military-style battle, as if it were fighting conventional insurgents from Latin America’s past, such as Colombia’s rural rebels. That is because, Davis argues in a pair of recent scholarly articles, Mexico’s cartels constitute “irregular armed forces” — well-organized, flexible urban gangs that make money smuggling drugs and other goods — buttressed by Mexico’s socioeconomic problems.

The cartels, Davis contends, are different from rebel groups: They aim not to remove the whole government, but instead to usurp some of its functions. “Their activities are not always motivated by anti-government ideals or regime change,” Davis states in a new article, “Irregular Armed Forces, Shifting Patterns of Commitment, and Fragmented Sovereignty in the Developing World,” published in the March issue of Theory and Society. Rather, the cartels use violence to protect their “clandestine networks of capital accumulation.”

By consensus of analysts, Mexican cartels now operate the most lucrative drug-smuggling routes into the Unites States, which had been under the control of Colombian groups in the 1980s and 1990s. The Mexican cartels now bring in from $10 billion to $25 billion annually from smuggling, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal this month.

In classic sociological theory, the state has a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence through military and police forces. But in Mexico, drug cartels challenge that monopoly, and more brazenly than ever. “Think of the armed forces linked to drug lords as a form of a ‘privatized army,’” says Davis.

The smuggling revenues of the cartels also give them staying power. “In cities, these groups have economic networks to supply the money to fight,” Says Davis. The resulting violence has reached levels that “resemble body counts from civil war battles,” as Davis writes. In the first half of 2009, Mexico saw an average of 127 cartel-related killings per week.

Narco-gang offer: ‘good salary, food, and help for families’

In Davis’ view, the massive urbanization of Mexico — more than 70 percent of Mexicans live in cities now, compared to about half in 1960 — has created social dislocations the cartels exploit. About 70 percent of Mexico’s urban labor force works in the “informal sector” of the economy, in transient jobs for small firms or in the world of black-market commerce. “As a result,” Davis writes, “much informal employment is physically and socially situated within an illicit commercial world” beyond the reach of the state, where violence occurs as gangs try to control drug supply routes. Moreover, informal workers are often not eligible for government safety-net benefits, making them even less invested in the success of the state.

Thus the cartels have been startlingly open about recruiting new members. In the city of Laredo in 2008, Davis notes, a drug gang called the Zetas hung a banner on a downtown bridge asking for “military recruits and ex-military men … seeking a good salary, food, and help for their families,” with a phone number posted for prospective enlistees. Other gangs were founded outside Mexico, but have spread inside the country: one such group, los Maras, was founded by “city-based youth who turned to criminal activity because of the lack of employment alternatives in the large metropolitan areas of California, Mexico, and Central America,” Davis writes in another article, “Non-State Armed Actors, New Imagined Communities, and Shifting Patterns of Sovereignty and Insecurity in the Modern World,” published in the August 2009 issue of Contemporary Security Policy. (In February, the article received the Bernard Brodie Prize, awarded to the best article appearing in Contemporary Security Policy each year.)

Mexico’s drug wars thus involve physically dispersed, evolving organizations that could be viewed more as self-sustaining networks than anti-state insurgents. “I think we still need to develop our analysis to better understand what’s going on in Mexico, and that’s why Davis’ contribution is so relevant,” states Fabio Armao, a professor of international relations at the University of Turin who studies organized crime.

A real long-term solution to Mexico’s problems, Davis notes, will require economic development, to lessen the influence of the drug trade and reduce the appeal of gang recruitment efforts. Such long-term economic changes have happened before: As The Wall Street Journal report stated, the cocaine industry has shrunk from an estimated 6 percent of Colombia economy in 1987 to under 1 percent today. Yet as The New York Times noted in March, of the more than $1 billion the United States has provided Mexico during the last two administrations, much has been for military and police equipment and training.

As Davis sees it, the Mexican government may be better equipped in the short run, but it still lacks a long-term perspective. And of the outlook in Washington, Davis says, “Attention is finally turning to Latin America, but the economic and policy contours have yet to be seen.” Among other things, Davis believes, the United States must work to limit its demand for drugs smuggled through Mexico. “I think some responsibility has to be accepted, and some re-thinking about trade and other incentives to get at the root of these transnational smuggling networks has got to be on the agenda. It is time for a paradigm shift.”