Worldwide, nearly 2 million people per year die from diarrhea, the vast majority of them in poor countries in Africa and Asia. The disease accounts for 18 percent of all deaths among children -- and yet is almost always preventable with proper treatment. Now, new research from MIT indicates that underlying, low-level undiagnosed infection may greatly add to the severity of a significant number of these cases. This realization could lead to changes in health-care strategies to address the problem.

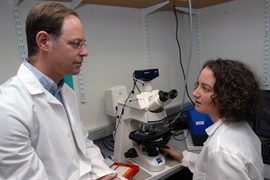

The findings, reported by MIT Professor of Biological Engineering and Comparative Medicine David Schauer, show that these undiagnosed gastrointestinal infections increase the severity of and delay recovery from acute diarrhea, and the analysis provides a model that could allow public health officials to evaluate new preventive strategies or therapeutic treatments.

The work grew out of the increasing recognition of the relationship between persistent, chronic infections many people carry and the outcomes of later disease infection.

"It seemed likely that persistent enteric infection with bacterial agents would also elicit immune responses that could have similar effects. However, this had not been previously studied," Schauer says. "We wanted to provide proof of principle, and begin to define the mechanism for such an interaction."

To study the possible effects of these chronic infections, Schauer and his team used laboratory mice infected first with a strain of bacteria that causes a chronic condition but produces no symptoms, and then with a second infectious agent that causes acute diarrhea. They found that even though the underlying chronic infection did not cause disease on its own, it did make the acute infection much worse than in a control group that was only exposed to the second agent.

Schauer and his team say as far as they know this is the first time, for any kind of disease, that an underlying "subclinical" infection has been shown to make a later bacterial infection more severe. And in the case of diarrhea, this may play a significant role, since about 50 percent of the world population carries a chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori, which causes stomach-lining inflammation but usually no clinical symptoms, and which is closely related to the initial infectious agent used in the mouse experiments.

"It may be that an individual's infection status with these or other agents is important in determining outcome of infection, immune-mediated disease or even immunization," Schauer says.

The work may also be significant in terms of understanding the results of much clinical research using rodent models. Infections similar to the chronic H. pylori "are now known to be widespread in many rodent facilities, and infection with these Helicobacter species does not cause clinical disease except in certain genetically engineered lines of mice," Schauer says, so "it is important to be aware of infection status with these agents when conducting research with laboratory rodents."

A report on the research was published last November in the journal Infection and Immunity, and was highlighted in December in Microbe magazine, both from the American Society for Microbiology. The work was carried out by Schauer and his students Megan E. McBee and Patricia Z. Zheng in the Department of Biological Engineering, and Arlin B. Rogers and James G. Fox in the Division of Comparative Medicine, all at MIT. The work was supported by a U.S. Public Health Service grant.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on February 25, 2009 (download PDF).