In our “Reporter’s Notebook” series, we feature first-person accounts of News Office writers on life at the Institute.

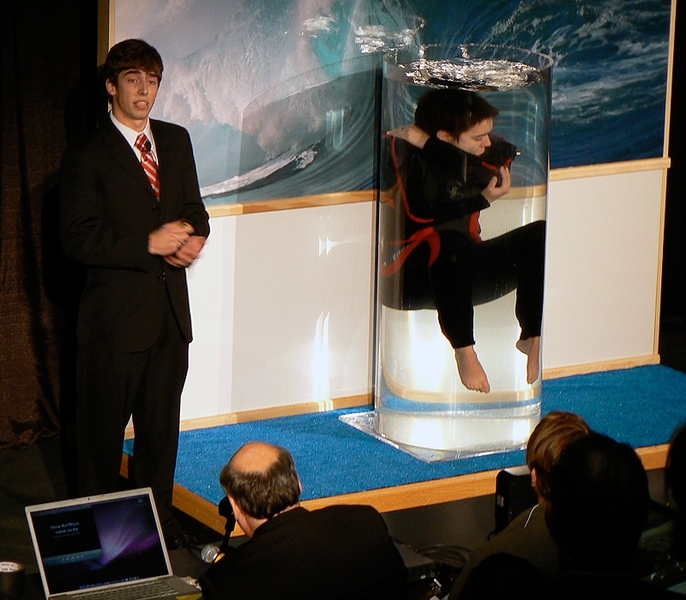

“Can somebody let her out of there?” asked an audience member plaintively.

“Her” was Taylor Williamson, a student in the Product Engineering Processes class (2.009), and she was trembling inside a 4-1/2-foot-tall glass cylinder full of water as part of a demonstration of her team’s product. She’d been submerged for several minutes while her teammates described the device — a system to provide an air supply to surfers who get knocked underwater by a big wave — and while they began to answer questions from the audience.

She looked quite relieved when her teammates, prodded by the questioner, offered her a ladder to climb out of the tank. “The water was ridiculously cold. They filled it from a garden hose that had been outside,” said Williamson, a senior in mechanical engineering. “My teammates brought a few buckets of warm water from the bathrooms to warm it up a bit. Then I was able to stay under for the full two minutes. I had been told not to move during the rest of the presentation so I would not distract from the presenters, but I couldn't stop from shivering.”

The team’s device, which they call “Airware,” looks like an ordinary wetsuit, but has concealed within it 16 feet of half-inch plastic tubing (enough to contain a few gulps of air), snaking across the back and down the legs, terminating at a regulator mounted on the sleeve, within easy reach of the wearer’s mouth.

The product is aimed at professional “big wave” surfers, and is intended to provide a few breaths of air in situations where the surfer is pulled far underwater by a crashing wave and may take some time to get oriented and make it back to the surface. The tubing is designed to be as flexible and unobtrusive as possible, so that the suit doesn’t restrict the surfer’s movements.

The system even comes with a tactile gauge, allowing the user to make sure by feel that there is still air left in the system before inhaling, “giving surfers the confidence to breathe,” explained team member Tylor Hess, who introduced the device to the assembled crowd at the Dec. 7 demonstration. Armed with clipboards holding evaluation forms, the audience members rated each of the eight teams’ inventions, along with their business plans and the quality of their demonstrations. Although the evaluations wouldn’t directly affect the team members’ grades, each team is given a summary of the ratings and comments they received, as way to help them refine their products and their presentations.

For the demo, Williamson climbed into the tank in darkness, and was seen floating there underwater, holding her breath, when the lights came on, providing a very dramatic opening for the evening. She then took a few breaths of air from the sleeve-mounted mouthpiece, before standing up to get her head above water. How did she get to be the lucky one to demonstrate the system? “I was the only one brave enough to test it the first time, and my team thought I did a good job,” she explained.

The class, taught for the last 13 years by Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Engineering Systems David Wallace MS ’91, PhD ’94, challenges students with a different theme each year. With just three months and a working budget of $6,000, each team, composed of about 16 students, has to come up with a specific issue to tackle, brainstorm ideas to address that issue, prototype and test various concepts, and develop a finished, professional-looking prototype in time for the class’s final presentations.

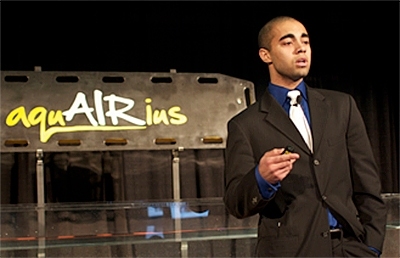

This year’s theme was “Emergency,” and the teams chose a wide variety of ways to interpret that. One group came up with a foldable litter with a backboard that breaks into four sections; the design would make it easier for rescuers to haul it up a mountainside to reach an injured climber, saving time and effort compared to presently available one-piece systems. Another team produced a backboard with inflatable compartments, to rescue injured swimmers from a pool. And two other teams devised new variations on the walkers often used to assist elderly people — one designed to help the person get up from a seated position, and another with a lift to help a person who has fallen on the floor to get back up without outside help.

Another team came up with a bicyclist’s equivalent of the OnStar system now available in some cars: a helmet-mounted sensor that could detect a crash and automatically dial 911, using a cellphone system mounted to the frame.

The class, Wallace said, is itself a kind of product that is constantly evolving and being improved. “Every year we do new things,” and he and his teaching assistants “pick what we think were the worst classes, and put a lot of effort into fixing those.” This year, he says, was probably the biggest class ever, with “a really nice group of projects, and very motivated students.”

Some teams from past 2.009 classes have gone on to form companies to commercialize their inventions, such as the team last year that developed a portable device to print Braille labels to help visually impaired people identify objects. That group has now launched a company called 6dot that aims to bring it to market.

That’s a nice bonus, but it’s not really the point of the class, Wallace said. It’s about learning the whole product development process. “In a typical year, maybe a couple of teams go through IP [intellectual property] filings, and there are maybe one or two startup companies. But the goal of the class is really about what they’re going to do for the rest of their lives. It’s really about 40 or 50 years of their career.”

“Can somebody let her out of there?” asked an audience member plaintively.

“Her” was Taylor Williamson, a student in the Product Engineering Processes class (2.009), and she was trembling inside a 4-1/2-foot-tall glass cylinder full of water as part of a demonstration of her team’s product. She’d been submerged for several minutes while her teammates described the device — a system to provide an air supply to surfers who get knocked underwater by a big wave — and while they began to answer questions from the audience.

She looked quite relieved when her teammates, prodded by the questioner, offered her a ladder to climb out of the tank. “The water was ridiculously cold. They filled it from a garden hose that had been outside,” said Williamson, a senior in mechanical engineering. “My teammates brought a few buckets of warm water from the bathrooms to warm it up a bit. Then I was able to stay under for the full two minutes. I had been told not to move during the rest of the presentation so I would not distract from the presenters, but I couldn't stop from shivering.”

The team’s device, which they call “Airware,” looks like an ordinary wetsuit, but has concealed within it 16 feet of half-inch plastic tubing (enough to contain a few gulps of air), snaking across the back and down the legs, terminating at a regulator mounted on the sleeve, within easy reach of the wearer’s mouth.

The product is aimed at professional “big wave” surfers, and is intended to provide a few breaths of air in situations where the surfer is pulled far underwater by a crashing wave and may take some time to get oriented and make it back to the surface. The tubing is designed to be as flexible and unobtrusive as possible, so that the suit doesn’t restrict the surfer’s movements.

The system even comes with a tactile gauge, allowing the user to make sure by feel that there is still air left in the system before inhaling, “giving surfers the confidence to breathe,” explained team member Tylor Hess, who introduced the device to the assembled crowd at the Dec. 7 demonstration. Armed with clipboards holding evaluation forms, the audience members rated each of the eight teams’ inventions, along with their business plans and the quality of their demonstrations. Although the evaluations wouldn’t directly affect the team members’ grades, each team is given a summary of the ratings and comments they received, as way to help them refine their products and their presentations.

For the demo, Williamson climbed into the tank in darkness, and was seen floating there underwater, holding her breath, when the lights came on, providing a very dramatic opening for the evening. She then took a few breaths of air from the sleeve-mounted mouthpiece, before standing up to get her head above water. How did she get to be the lucky one to demonstrate the system? “I was the only one brave enough to test it the first time, and my team thought I did a good job,” she explained.

The class, taught for the last 13 years by Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Engineering Systems David Wallace MS ’91, PhD ’94, challenges students with a different theme each year. With just three months and a working budget of $6,000, each team, composed of about 16 students, has to come up with a specific issue to tackle, brainstorm ideas to address that issue, prototype and test various concepts, and develop a finished, professional-looking prototype in time for the class’s final presentations.

This year’s theme was “Emergency,” and the teams chose a wide variety of ways to interpret that. One group came up with a foldable litter with a backboard that breaks into four sections; the design would make it easier for rescuers to haul it up a mountainside to reach an injured climber, saving time and effort compared to presently available one-piece systems. Another team produced a backboard with inflatable compartments, to rescue injured swimmers from a pool. And two other teams devised new variations on the walkers often used to assist elderly people — one designed to help the person get up from a seated position, and another with a lift to help a person who has fallen on the floor to get back up without outside help.

Another team came up with a bicyclist’s equivalent of the OnStar system now available in some cars: a helmet-mounted sensor that could detect a crash and automatically dial 911, using a cellphone system mounted to the frame.

The class, Wallace said, is itself a kind of product that is constantly evolving and being improved. “Every year we do new things,” and he and his teaching assistants “pick what we think were the worst classes, and put a lot of effort into fixing those.” This year, he says, was probably the biggest class ever, with “a really nice group of projects, and very motivated students.”

Some teams from past 2.009 classes have gone on to form companies to commercialize their inventions, such as the team last year that developed a portable device to print Braille labels to help visually impaired people identify objects. That group has now launched a company called 6dot that aims to bring it to market.

That’s a nice bonus, but it’s not really the point of the class, Wallace said. It’s about learning the whole product development process. “In a typical year, maybe a couple of teams go through IP [intellectual property] filings, and there are maybe one or two startup companies. But the goal of the class is really about what they’re going to do for the rest of their lives. It’s really about 40 or 50 years of their career.”