More than 11 million cargo containers enter U.S. ports annually and that number is expected to dramatically increase in the next 20 years. The U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents might benefit from technology developed by an MIT professor, which could enable screeners to examine the contents of a cargo container for the presence of radiological or nuclear material without having to open the container.

MIT Professor William Bertozzi's new technology reveals the cargo's atomic composition, which is an enhancement over current systems. The technology could also be used for cargo validation for tax revenue compliance, product safety or origin certification.

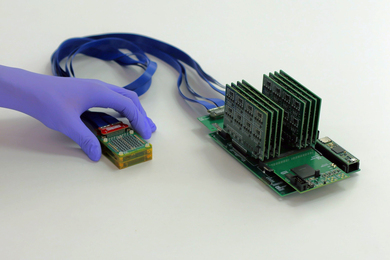

Bertozzi and private-capital backed Passport Systems Inc., are developing the technology, known as nuclear resonance fluorescence imaging (NRFI), with additional funding from the Department of Homeland Security and Office of Naval Research.

Unlike X-rays, which only reveal the two-dimensional shape of an object, NRFI can determine the atomic composition of cargo -- whether it's a harmless shipment of televisions or a load of radioactive uranium-235, which can be used to make a nuclear bomb.

Bertozzi, along with former MIT professor Bob Ledoux and Gordon Baty '61, SM '63, PhD '67, founded Passport Systems in 2002. At the time, they intended to use their detectors to find traditional explosives, but in the past few years, the company and the U.S. government have also turned its attention to detecting nuclear threats.

"We're in a very different realm than what we originally thought it would be used for," Ledoux said.

Bertozzi, a professor of physics, first came up with the idea more than 15 years ago, after Pan Am Flight 103 was blown up by terrorists. As a graduate student at MIT, Bertozzi had studied nuclear resonance fluorescence, though it wasn't his main research focus.

"All of the sudden it dawned on me that this might be a viable technique" to detect explosives, he says.

Bertozzi patented his idea and several companies were interested in developing the technology but the government's interest waned, and the project didn't get off the ground. However, everything changed after Sept. 11, 2001, and Bertozzi resurrected the idea.

"The damage to our nation's economy from the effects of an attack through the supply chain with a nuclear weapon (WMD) would be enormous and would adversely affect all segments of our population, seriously altering our nation's culture," Bertozzi said. "We are developing new technologies that will provide significant improvement over existing nonintrusive inspection technologies to help ensure that our nation is safe from such attacks."

In about a minute, the detector can determine what's inside a container, without opening it. And unlike X-rays, NRFI can detect the isotopic composition of a material even when it's shielded by lead.

NRFI technology detects the energy level of photons emitted by nuclei as they decay. Every element, and every isotope of an element, emits photons with a specific energy level. Thus NRFI can distinguish not only between different elements, but different isotopes of the same element, such as uranium-235, which is used in nuclear weapons, and uranium-238, which is not.

Such detectors could also help protect U.S. economic interests by checking to make sure a container reportedly filled with, for example, low-grade stainless steel products isn't actually carrying higher grades that would look the same to an X-ray scanner and thus avoid payment of the correct tariffs. The applications for verification in commerce are numerous.

Ledoux says the company has a good grasp on the science underlying the detection system and has identified signatures for the bomb-making materials they are trying to detect. They have recently completed a successful test of the technology for the U.S. government and are now looking to develop commercial products.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on September 24, 2008 (download PDF).