The tale of the Cape Cod cleanup has all the elements of an epic novel: It's long. It offers intrigue, heroes and plot twists. And, of course, it changes the world.

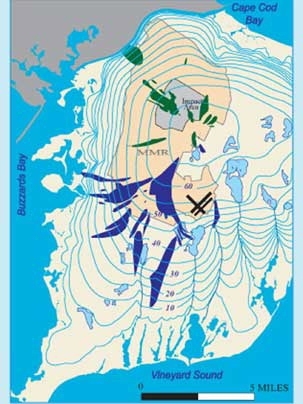

Denis LeBlanc, who has spent much of his career studying the hydrology of western Cape Cod, described in a talk on April 9 how the investigation into a single "plume" or tongue of contaminated water underground became a 25-year gold mine of hydrology research and fueled an ongoing effort to rid the Cape's groundwater of pollutants.

"This is a very complicated and very expensive project involving hundreds of people. I'm going to tell one part of the story: how our understanding of the groundwater hydrology in Western Cape Cod has been shaped by this work," said LeBlanc, an MIT alumnus (S.M. 2001) and hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, who presented the 2007 Freeman Lecture, hosted annually by the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE).

Peter Shanahan, a senior lecturer in CEE who introduced LeBlanc, said that researchers working on the site have produced 126 journal articles, 140 USGS studies and 50 theses and dissertations from 15 universities, "including one fundamental paper that changed the way people think about dispersion in groundwater systems."

The USGS began studying the hydrology of the Massachusetts Military Reservation (MMR) wastewater treatment facility near Ashumet Pond in 1983. At about the same time, the Department of Defense began the process of cleaning up environmental damage at military installations. The USGS pointed the DOD to a single plume of treated wastewater, with the assumption that toxins from the military base were likely to be found. Nobody realized at that point that the plume and the process would balloon into a decades-long, billion-dollar project.

"I think if we had known the real history of waste disposal at the MMR, we'd have known the plumes were much greater in extent. But that is hindsight," LeBlanc told the audience of civil and environmental engineers in Wong Auditorium.

The military reservation has a distinguished history over the past century, serving as a staging area during World War II for troops heading to Europe and as Otis Air Force Base during the Cold War. Today the area is home to the Army National Guard, the Coast Guard, the Air National Guard, a military cemetery and a number of environmental programs.

Researchers began following the plume, which they soon learned was several plumes, by drilling and sampling. As work progressed, the scope of the cleanup had to be changed, and changed again with the discovery of new plumes that traveled further than anticipated, the finding of different contaminants and the growing understanding of the Cape's hydrology.

One very important hydrological discovery arising from the research is that underground plumes don't dead-end at lakes and disperse into the reservoirs of freshwater. Instead, a plume can change course to flow under a lake and continue on an altered path.

The scope of work now includes an Army National Guard training range covering 14,000 acres, one of the largest undeveloped areas in eastern Massachusetts. Plumes from this area contain chemicals from munitions such as explosive compounds and perchlorate, a propellant. The source of one perchlorate plume, discovered in December 2003, has been traced to the launch site of a nearby town's annual fireworks display. That plume originates along the trail where fireworks' debris falls and eventually soaks into the ground with rainwater.

By the end of 2007, the cleanup will have cost $925 million, with $460 million more budgeted, bringing the projected cost to $1.4 billion. More than 6,000 sampling wells have been drilled. The U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, Massachusetts National Guard and USGS are working together on the project.

Much progress has been made on the 11 plumes that contain solvents and fuels, the first contaminants discovered. At present, 53 extraction wells pump out 17.5 million gallons of water each day, which, after treatment, is pumped back into the ground to maintain the water table. Work on the explosives and perchlorate, "the contaminant du jour," is just getting under way, LeBlanc said.

He predicts the tale will not end entirely, but the damage will have been mitigated. "The plumes will remain, but be dilute and patchy. The focus will change to plume management in the context of water supply," said LeBlanc.

The Freeman Lecture is presented annually by CEE and the Boston Society of Civil Engineers to honor the late John R. Freeman, a CEE alumnus who designed the original Charles River Dam.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on April 25, 2007 (download PDF).