If you spotted an anaconda poised to strike, the signal to pay attention would originate in a different part of your brain than if you gazed at an anaconda in the zoo, neuroscientists at MIT's Picower Institute for Learning and Memory report in the March 30 issue of Science.

The work, which could have implications for treating attention deficit disorder (ADD), is the first concrete evidence that two radically different brain regions--the prefrontal cortex and the parietal cortex--play different roles in these different modes of attention.

What's more, when you focus your attention, the electrical activity in these two brain areas synchronizes and oscillates at different frequencies. "It's as if the brain is using two different stops on the FM radio dial for different types of attention," said study co-author Earl K. Miller, Picower Professor of Neuroscience.

Top to bottom

Brain signals related to the knowledge we have acquired about the world are called top-down. Signals related to incoming sensory information are called bottom-up.

"Loud, flashy things like fire alarms automatically grab our attention," Miller said. "By contrast, we choose to pay attention to certain things we think are important. We found two different modes of brain operation related to each, and they seem to originate in different parts of the brain. Further, the automatic (or bottom-up) versus willful (top-down) modes of attention seem to rely on two different frequency channels in the brain, suggesting that the brain might communicate in different frequency bands for different types of signals."

ADD involves being overly sensitive to the automatic attention-grabbers and less able to willfully sustain attention. "Our work suggests that we should target different parts of the brain to try to fix different types of attention deficits," Miller said.

"The downside of most psychiatic drugs is they are too broad," he continued. "It's like hitting the problem with a sledgehammer; you get the benefits but also many unintended consequences. Our work suggests that we may one day be able to figure out what is the exact problem with each individual and specifically target those shortcomings. And that is the ultimate goal in psychiatric intervention."

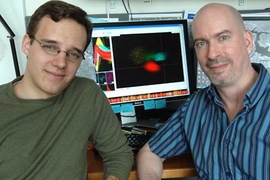

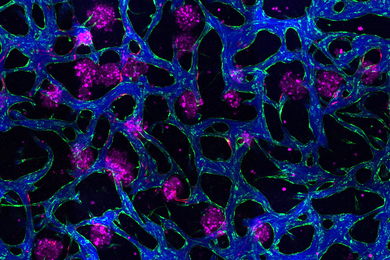

To address the fact that neural activity from the prefrontal and parietal cortices had never been directly compared, Miller and co-author Timothy J. Buschman, an MIT graduate student in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, conducted a series of experiments in which monkeys were engaged in different kinds of tasks. The researchers looked at activity in two areas of their brains simultaneously--the prefrontal cortex, also called the brain's executive because it is in charge of voluntary behavior, and the parietal cortex, which integrates sensory information coming from various parts of the body.

The monkeys had to pick out rectangles of certain colors and orientations on a video screen. Some of the rectangles popped out at them like the anaconda in the forest; others they had to search for.

The results support the idea that when something pops out at us, sensory cortical areas like the parietal cortex directs our eyes toward the stimulus. When we purposefully look for something, the prefrontal cortex is doing the driving.

"Taken together, these data suggest two modes of operation: When a stimulus pops out, a bottom-up, fast target selection occurs first in the posterior visual cortex; while in search mode, a top-down, longer latency target selection is reflected first in the prefrontal cortex," Miller said. "To our knowledge, these are the first direct demonstrations that these areas may have different contributions to these different modes of attention."

This work is supported by the the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and an NSF CELEST Science of Learning Center.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on April 4, 2007 (download PDF).