MIT researchers have a new understanding of the process cells use to ensure that sperm and eggs begin life with exactly one copy of each chromosome -- a process that must be exquisitely regulated to prevent problems such as miscarriages and mental retardation.

The new work reveals how gluelike protein complexes release pairs of chromosomes at precisely the moment of meiosis -- the specialized cell division process that produces sperm and eggs -- enabling them to separate properly.

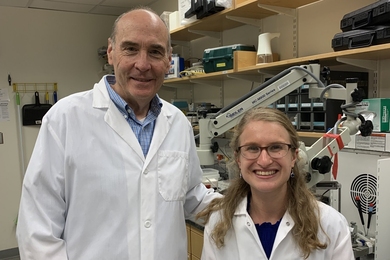

The researchers are led by Angelika Amon, an associate professor in MIT's Department of Biology, a member of MIT's Center for Cancer Research, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. The work was published online in the May 3 issue of Nature.

Most cells in the human body -- all those other than sperm and eggs -- contain 23 pairs of chromosomes. These cells divide through mitosis, a process that creates daughter cells with the same complement of chromosome pairs as the parent. Sperm and egg cells, on the other hand, must contain only half the chromosomes of their parent cells, so that the normal chromosome number will be restored when the sperm and egg unite during fertilization. To achieve this, they are produced through meiosis.

Gluelike protein complexes called cohesins, which hold the members of a chromosome pair together until just the right moment during cell division, are central to both processes. Bound together by cohesins, chromosome pairs must organize themselves in preparation for cell division before they can be released.

According to Amon, a deeper basic knowledge of the mechanism of cohesin loss during meiosis could ultimately improve understanding of the origins of miscarriages and mental retardation due to mis-segregation of chromosomes.

"We first need to understand the key regulatory players and the molecular mechanisms that cause chromosomes to segregate in this very unusual way during meiosis," she said. "Once we have a good enough understanding, then we can ask, for example, what exactly happens to cohesins in older women that make them more likely to give birth to children with an abnormal chromosome number."

Amon's co-authors on the Nature paper are Gloria A. Brar and Brendan M. Kiburz, both graduate students in biology; Forest White, assistant professor in the Division of Biological Engineering (BE); Yi Zhang, a BE graduate student; and MIT affiliate Ji-Eun Kim.

Knowledge about the mechanism of cohesin function has remained sketchy, even though it plays a central role in meiosis. Researchers knew that an enzyme called separase snips apart cohesins, targeting a specific subunit of the cohesin complex called Rec8. Also, Amon said, researchers had found that Rec8 cleavage was promoted by phosphorylation -- the addition of chemical phosphate groups -- of Rec8.

Researchers also knew that cohesins release chromosome pairs from one another's embrace quite differently during meiosis and mitosis. In mitosis, cohesins release chromosomes along their entire length simultaneously. However, in the initial stage of meiosis, cohesins first release only the "arms" of chromosomes, still holding the chromosomes together at their central connection point, the centromere. Only in a second stage of meiosis that gives rise to haploid sperm or egg cells do centromeric cohesins become cleaved. This precisely controlled centromeric "stickiness" is essential for the accurate segregation of sister chromatids into separate cells.

"The key question we wanted to explore was how this step-wise loss of cohesins in meiosis was regulated," said Amon. "It could be that the enzyme separase was the key regulatory player, or it could be that it was the phosphorylation of cohesins that was central."

To find out, the researchers experimented with yeast cells, selectively mutating the Rec8 subunit so that it could not be phosphorylated. They then studied how the cell's inability to phosphorylate Rec8 affected meiosis. Those experiments showed that phosphorylation is, indeed, important for governing the step-wise loss of cohesins, said Amon.

Amon and colleagues found that phosphorylation was not the only process essential for cohesion removal. Recombination -- an exchange of DNA between chromosomes that promotes genetic diversity -- is also needed for the initial removal of cohesin from the chromosome arms, they found.

In meiotic recombination, after each member of a chromosome pair has replicated to produce identical sister chromatids in the initial stage of meiosis, the chromosomes exchange arm segments. Only after this exchange, or recombination, do the cells proceed to the second stage of meiosis -- dividing without chromosome replication to produce haploid sperm or egg cells. Recombination is essential for cohesins to get removed from chromosome arms before they are removed from centromeres, Amon said.

"For a long time, people did not think that recombination played any role in establishing the step-wise cohesin loss pattern," she said. "But our experiments showed that recombination is absolutely essential to remove cohesins from chromosome arms during the initial meiotic stages, and if you don't have recombination that does not happen properly."

Amon emphasized that the discovery of the importance of phosphorylation and recombination is only the beginning of understanding the intricate, critical process of cohesin loss. "There are no doubt other mechanisms at work in cohesin loss, but at this point we don't know what they are," she said.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on May 10, 2006 (download PDF).