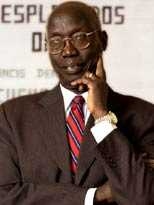

The seemingly simple question, "How many brothers do you have?" produces a soft chuckle from Francis Deng, a former Sudanese ambassador to the United States and now a visiting fellow at MIT's Center for International Studies (CIS).

"That is a good question. The answer will shock you," said Deng, who was born in the Abyei area of Sudan, an isolated area bordered by the Arab-influenced Muslim north and the African Christian-influenced south. His father, as his grandfather and great-grandfather before him, was a "paramount chief" of the Ngok Dinka tribe.

"My father, by the time he died, had over 200 wives," Deng explained. Thus, he had close to 1,000 brothers and sisters, all part of a structured, extended family.

Deng and some of his brothers were the first in the family to attend local primary school; Deng went on to study at the University of Khartoum, Oxford University in England and Yale University before embarking on a distinguished academic and diplomatic career. Deng is now a fellow at the Brookings Institution and director of the Center for Displacement Studies at Johns Hopkins University .

Appointed in May as a Robert E. Wilhelm Fellow at CIS, Deng will conduct research and help to raise awareness about Sudan, a country wracked by genocidal violence that is rooted, Deng believes, in differing perceptions of national identity.

Indeed, the question of Sudanese identity has been a thread through Deng's personal life, academic research and diplomatic efforts. "It's a country torn apart by myths of identity that are so divisive and not reflective of realities," Deng said. The Muslim north perceives Sudan as culturally and ethnically linked with the Arab world, and the south sees itself as African with Christian influences. Violence between the two regions has erupted periodically since the early 1900s in what Deng calls a "war of identities," in which "by its very nature, 'your existence challenges my existence.'"

Americans have recently focused on horrific stories of massacres by Arab militias in the western Darfur region, but "what the world doesn't know is what is happening in Darfur has been happening for decades in the south," Deng said. "I think the reason people are conscious of what's happening in Darfur is because of Rwanda," where millions of people were killed in an ethnic conflict.

"This is not to play down (the Darfur violence) but to say that if you're dealing with the problem in Sudan, don't deal with the problem in isolation. You have to deal with the country as a whole and the distortions that have afflicted this country," he said.

As a young academic, Deng explored the roots of national identity through research on "customary law," or laws derived from native customs, and on the cultural values reflected in native song.

He later served as the Sudanese ambassador to the Scandinavian countries, Canada and the United States and as minister of state for foreign affairs. ��From 1992 to 2004, as a representative of the United Nations Secretary-General on Internally Displaced Persons, Deng worked on the issue of internally displaced persons, or IDPs, those forced to flee homelands but who lack international protection because they do not cross national boundaries.

In that role, he visited Darfur at the peak of the violence, which displaced millions of people, to press the Khartoum government for a solution. While the Clinton administration had viewed Sudan as not vital to U.S. foreign interests, President George W. Bush "surprised everybody by showing the interest that he has shown with the appointment of Sen. (John) Danforth as his envoy," Deng said.

A peace accord was brokered this spring between the government and one of the several southern rebel groups, which is evidence, Deng said, that international attention can be effective. "This is the area where I saw the war against terror produce some very constructive results."

The peace accord remains fragile, but Deng rejects pessimism. "We must assume that even though the impact of what you do compared to the magnitude of the problem is miniscule, there is some faith that it can make a little difference."