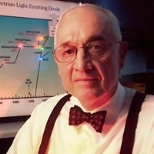

Nick Holonyak, inventor of the LED (light-emitting diode), and Edith Flanigen, whose pioneering work in chemistry and materials science helped make petroleum refinement cleaner and safer, have both won Lemelson-MIT prizes.

Holonyak will receive the $500,000 Lemelson-MIT Prize for Invention -- the world's largest single cash prize for invention -- at a ceremony on Friday, April 23. At the same ceremony, Flanigen will receive the $100,000 Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award, which recognizes her cumulative contributions to technological progress and invention.

Light from a chip

Holonyak invented the first practical LED in 1962. Today, LEDs illuminate everything from alarm clocks to the NASDAQ billboard in New York's Times Square. LEDs produce more lumens per watt than both incandescent and halogen lights, making them more environmentally friendly and cost-effective. And their long lifespan makes them ideal for use in automotive dashboards and taillights, traffic signals and consumer electronics displays.

Holonyak continues to refine his original invention and pursue new applications for it. His current research with colleague Milton Feng is in light-emitting transistors, which could dramatically improve the speed and availability of electronic communications.

Holonyak was the first student of John Bardeen, one of the inventors of the transistor, at the University of Illinois in the early 1950s. After finishing graduate school in 1954, Holonyak took a job with Bell Labs and was part of a team whose work led to the invention of the integrated circuit. Later, at General Electric, Holonyak invented the shorted emitter p-n-p-n switch, now widely used in household dimmer switches and power tools.

"I learned pretty early in life that you don't have to learn everything to be able to do something. With inventing, you are attempting to solve a problem within your reach, not trying to resolve the world's greatest problems," said the 75-year-old Holonyak. "I tell my students, 'You only have to succeed once, and then you'll have the confidence and a basis of knowledge for continued successes.'"

Today, Holonyak is the John Bardeen Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Physics at the University of Illinois, a professorship sponsored by Sony. He has taught at his alma mater since 1963. During his 41-year tenure, he has mentored more than 60 doctoral candidates.

Creating new materials

"Many people may not know about Edith Flanigen's discoveries, but her inventiveness and creativity have greatly affected everyone's life," said Professor Merton Flemings, director of the Lemelson-MIT Program. "Her discoveries have resulted in more than 100 patents and have revolutionized the world of molecular sieve materials."

Flanigen's pioneering work in chemistry and materials science over the past four decades has helped make the petroleum refinement process more efficient, cleaner and safer.

Flanigen began her distinguished career in 1952 as a research chemist at Union Carbide in Tonawanda, N.Y. She and her two sisters all worked at Union Carbide at a time when few women were making strides in the sciences. She eventually became the first woman to hold the company's highest technical position, senior research fellow.

Her most important work led to the development of a new generation of molecular sieves, which are porous crystals that can separate molecules on the basis of size. Flanigen and co-workers discovered a large number of novel structures and compositions of molecular sieves, which enabled their use in a wider range of applications. Molecular sieves are now used in everything from converting crude oil into gasoline, to cleaning up nuclear waste.

Flanigen also co-invented a material called silicalite, which is widely used in environmental cleanup applications to selectively adsorb organic compounds. Additionally, she developed a synthetic emerald that was designed for use in masers -- a predecessor to the laser that was based on microwaves instead of light.

Equally important as her own discoveries, Flanigen has inspired generations of scientists to improve and explore new applications for molecular sieves.

"Our discovery of the new generation of molecular sieves showed the inorganic materials world that there was a lot to do. Once we published that work and it was patented, everyone working in the field began also to be more creative and to generate new compositions and new structures," said Flanigen.

"Edith mentored and inspired countless young scientists within Union Carbide and UOP [a joint venture between Union Carbide and Allied Signal], as well as throughout the world in academia and industry," said Geoffrey Ozin, a materials chemistry professor at the University of Toronto. "Her work strongly influenced my research direction at a key point in my academic career. She was a great teacher and mentor."

Flanigen, who is now 75, retired in 1994 and now consults to UOP.

Nurturing invention

The Lemelson-MIT Lifetime Achievement Award promotes living role models in the fields of science, engineering, medicine and entrepreneurship in the hope of encouraging future generations to follow their examples. As part of her acceptance of the award, Flanigen participated in a Congressional briefing about the future of scientific exploration and invention in the United States, one of several events during the first Invention Assembly, a gathering of professional inventors and academics who will discuss ways and recommend policies to preserve an inventive culture in the United States.

"The growth of the United States has largely been based on inventions. And our prosperity has largely been based on inventions," Flanigen said. "Inventiveness starts long before children go to school. Parents and teachers really need to get children curious about how things work and how to make them better. I don't see that students today are getting anything in the normal curriculum, including the sciences, that really stimulates curiosity, creativity and innovation."