Sunita lives in a small village near the baking hot city of Ahmadabad in the Indian state of Gujarat. Born blind, she spent the first 12 of her 30 years sitting in a corner of her disabled, poverty-stricken parents' home, moving around only when she could feel her way.

At age 12, her family received a subsidy that paid for an inexpensive surgical procedure that removed her cataracts, giving her limited vision in one eye. With the help of thick-lensed glasses, she sees well enough to work as a maid, supporting her husband, who also has vision problems. Their 4-year-old blind daughter recently had the cataract operation, but is now in an orphanage because her parents cannot afford to care for her.

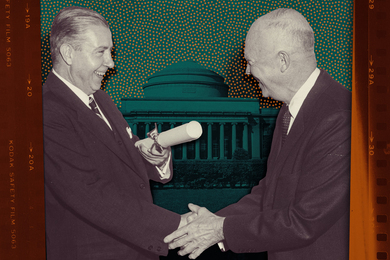

Sunita (not her real name) and her family are a few of the people that Pawan Sinha, assistant professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT, met during a seven-week trip to India this summer as part of Project Prakash ("light" in Sanskrit).

Project Prakash is Sinha's ambitious scientific and humanitarian effort to look at how individuals who are born blind and then gain some vision perceive objects and faces. As part of the project, Sinha, who grew up in New Delhi, will fund the cataract operation for some children whose families cannot afford it. He also hopes to educate Indian health care workers on ways to help children who emerge abruptly from a world of darkness into a world of shadows and patterns as they literally learn to see.

"Merely treating the eyes is not enough," Sinha said. "For blindness programs in India to be effective, they need good follow-up rehabilitation. A child's brain has to be able to correctly process visual information after being deprived of it for so long."

Earlier studies have shown that in many cases, individuals who recover sight after prolonged blindness battle severe mental health problems. Some threaten to tear out their eyes or simply continue to act blind. Some are so depressed they commit suicide. Sinha hopes to design techniques for individuals to overcome the face processing deficiencies that may be contributing to these problems.

According to the World Health Organization, India has the world's largest population of blind children, which exacts a great social and economic cost. Nearly 20 percent of these children have treatable conditions such as congenital cataracts. Poverty, ignorance and lack of simple diagnostic tools in rural areas deprive these children of the chance for early treatment, relegating many to lifelong poverty or intermarriage to blind relatives, which only perpetuates the problem.

While the incidence of childhood blindness in developed countries is less than 0.3 per 1,000 births, it is more than 2.5 times higher in India. Recent government initiatives have led some hospitals to launch outreach programs to identify treatable children, many of whom live unnecessarily in homes and schools for the blind.

For Sinha, who studies face perception, the blind Indian children present a unique scientific opportunity. Using EEG equipment to assess noninvasively the spatial distribution of children's brain activity before and after the operation, he will record evidence of how the brain rearranges its use of neurons to respond to new external stimuli. Among the questions he hopes to answer: How soon after sight is restored do different face perception skills emerge, and is there any evidence of innate abilities in this regard? Which face perception skills are compromised by early visual deprivation? What are the critical periods for their development?

Sinha's collaborators in addressing these questions include Richard Held, emeritus professor of brain and cognitive sciences who has conducted pioneering studies of visual learning in animals, and Beatrice deGelder of Tilburg University in the Netherlands, a leading figure in the study of face perception disorders.

Sinha and MIT brain and cognitive sciences graduate students Yuri Ostrovsky and Aaron S. Andalman braved record-breaking 120-degree heat and weeklong bouts of intestinal illness to travel to hospitals in the south and west of the country. They met doctors who performed the operation and patients who had recently undergone it. Sinha spoke to hospital staff about visual neuroscience and the need for continued intervention, and the students gathered information to allow them to design and run experimental studies on the children in the future.

Human resilience

While scientists have long known that temporarily depriving one eye of vision in kittens soon after birth induces a loss of synapses that causes permanent blindness, Sinha is finding that human brains are more flexible than animal brains.

The cataract surgery, which involves a painless 3mm incision in the cornea and insertion of a flexible corrective lens costing $1.50, is still beyond the financial reach of many. And the doctors' goal for those who have the operation is the ability to get around without help, not to read or recognize faces. But some do achieve abilities beyond expectations.

In one facility, Sinha tested an 11-year-old boy whose vision had been restored five weeks earlier. The boy had enough eye-hand coordination to pick up paper clips and place them into a holder through a small opening, catch a balled-up piece of paper thrown to him and identify hand-drawn pictures of animals. Sinha found this an astounding display of the brain's ability to adapt. Sunita also is an unusual case history because she regained vision so late in life. Sinha thinks he may find other examples of just how resilient the human brain--and spirit--can be.