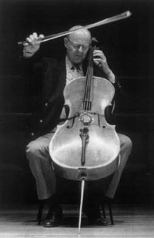

When world-class cellist Carlos Prieto graduated from MIT, he had no intention of carving out a career in music. He received three degrees--one in engineering in 1958, and two more in metallurgy and economics, politics and engineering in 1959--and left the Institute to work in the iron industry in his home country of Mexico, where he still lives. At the age of 38, he decided that he should either go back to the cello or, he said, "be sorry for the rest of my life."

The New York Times review of his 1984 Carnegie Hall debut said, "Prieto has no technical limitations and his musical instincts are impeccable." In addition to his award-winning performing and recording career, Prieto has written five books and is now working on "5,000 Years of Words," a book about languages. He has also served as a member of the Music and Theater Arts Visiting Committee since 1993.

Tonight (March 5), he returns to MIT for a talk and concert sponsored by the MIT Western Hemisphere Project at 8 p.m. in Killian Hall. Lynn Heinemann of the Office of the Arts spoke to him by phone about musical shifts his life has taken.

Q. How did you begin playing the cello?

A. There is a long tradition of string quartet playing in my family, going back to 1918. When I was born, my mother had already bought a child's violin-sized cello because they needed a cellist in the family. I don't even remember when I first started playing.

Q. Were you involved in music while at MIT?

A. For the first two years, I only played chamber music on weekends with two Dutchmen--the head of what was then the Department of Naval Architecture, Professor [Laurens] Troost, a pianist who was absolutely crazy about music; and Professor Den Hartog, the head of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and a world-famous expert on vibration, who played the violin. Then I was invited to join the MIT Orchestra, which I hadn't joined before because I thought I would not have enough time. I was soon appointed first cello and I also played as soloist.

One of my most important experiences at MIT was in the Music Library, where I would spend endless hours listening to music. I discovered the music of Shostakovich and was immediately fascinated with his music and his personality. I became so interested that, without knowing any Russian, I bought a subscription to a Soviet music magazine. This was in the 1950s, and I think receiving this mysterious monthly package from Russia caused my neighbors on East Campus to wonder if I was a Soviet spy. I took all the available courses in Russian at MIT so I could read the magazine.

Q. Was there a pivotal moment that caused you to focus on music after many years in the iron industry?

A. I was very busy with my career in Monterrey, Mexico. Only while on vacation, the thought would occur--each time more acutely--that maybe I should have devoted my life to music and not to engineering.

In 1960, my knowledge of Russian led to a very important event in my life. The first Soviet delegation to Mexico came to Monterrey. Their interpreter fell sick and, lacking a better solution, they contacted me. Afterwards they asked if I'd be interested in going to the Soviet Union to study, and of course I answered yes.

While studying at the University of Moscow, I read that Igor Stravinsky was in the Soviet Union for his first visit since leaving 50 years before. My family had been close friends with Stravinsky and I had known him since I was two years old. He was kind enough to invite me to all their rehearsals and concerts, which got me very involved with musical life in Moscow. To me, the highlight of that stay in the Soviet Union was the contact with Stravinsky and the chance to meet Shostakovich, who, after all, was responsible for my having studied Russian.

That was the first moment when I had tremendous doubts: should I abandon my professional engineering career and go back to music? But when I went back to Mexico I got married, had three children and made fast progress in the industry. It took many more years before I suffered an "inner crisis," thinking that this was my last chance to devote my life to music.

Q. Tell me about your instrument.

A. The moment I bought my Stradivarius in 1978, I became very interested in learning its 300-year history. I took advantage of my concert tours to follow the cello's footsteps in the places I knew it had been. That research became my book, "The Adventures of a Cello." For example, I knew that my cello had been in Ireland for 35 years. In 1825, the Irish had called it 'the red Strad' or 'the Irish Strad.' The first time I was in Ireland, I said I would be grateful to be able to go back to Ireland someday with this Irish Strad to play the world premiere of a work by an Irish composer.

Composer John Kinsella contacted me and last year I played the world premiere of his cello concerto in Dublin with the National Irish Orchestra.

I call the cello 'Miss Cello Prieto' because I used to lose a lot of time trying to explain that I was buying an extra airline ticket for a cello. Now I make the booking as if it were a woman, but whenever I want to use its frequent flyer miles, I have to falsify her signature.

Carlos and Miss Cello Prieto will perform selections by Bach and Kodály, preceded by a short talk, on Wednesday, March 5 at 8 p.m. in Killian Hall. For more information, call 253-2906.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on March 5, 2003.