Switch fixing

"Home Repair for Women: Electrical Work," a four-week IAP course, taught the basics of plugs, circuit, switches and light fixtures. Here, master electrician Joe Fagone explains the installation of dimmer switches to Kristen Jellison (right foreground), a civil and environmental engineering graduate student, while freshmen Angela Chen (left background) and Maya Dobuzhskaya install dimmer switches on a board.

Tiny, agile helicopters whirl with development potential

After five hours of watching an elite helicopter pilot fly his machine upside down and otherwise execute a variety of acrobatic maneuvers, Eric Feron walked away with a new research objective while his family simply wanted to go home.

At a January 24 IAP talk, the associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics shared his excitement in developing small, agile robotic helicopters that could one day lead to tiny unmanned air vehicles with applications such as civilian and military surveillance and farmland imaging. "Our ultimate goal is to create the first robotic flying bird," he said.

Two years ago, when the project began, Professor Feron and colleagues bought a miniature helicopter about four feet long. Flight tests with the machine determined how much weight it could carry and still fly well. That answer in hand (seven pounds), the researchers outfitted the helicopter with a small box of about that weight including sensors, a GPS receiver for determining location, a compass and a computer.

As a result, the helicopter can record information while it flies that in turn "is used to create a computer simulation of the action," said Professor Feron, who showed side-by-side videos of the real machine in flight and the resulting simulation. "Our main achievement here is that we can record information while the helicopter maneuvers. Our machine is the first to do that."

The team's overall goal is to develop a machine that can complete complicated acrobatic maneuvers. "By the end of the summer, we hope to achieve an autonomous snap roll," said Professor Feron, who is also faculty advisor for the MIT Aerial Robotics Club. That team has developed past robotic helicopters that have competed at national competitions but do not have the same potential for agility as the machine he is currently developing.

Professor Feron also has appointments in the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems, the Operations Research Center and the International Center for Air Transportation. His collaborators include researchers at Draper Labs.

Elizabeth Thomson

Good personal connection could offer best antidote to suicide

Suicide. It's a subject few people want to talk about, with the exception of the four who attended the IAP course, "When a Friend Is Thinking About Suicide."

The MIT Medical-sponsored class, conducted as an informal question-and-answer session, was co-facilitated by Dr. Robert Randolph, an ordained minister who also is senior associate dean for students, and Dr. Margaret Ross, a psychiatrist with MIT Medical.

Although it's a rare topic of conversation, suicide is not a rare occurrence.

More suicides than homicides are reported in the United States every year, according to the US Surgeon General's report. Dean Randolph quoted statistics from that report stating that 31,000 suicides were committed in 1996, and 20,000 homicides. While most people loudly denounce murder, they discuss self-murder quietly, or not at all.

People fear discussing the issue for many reasons: religious taboo, privacy invasion, or a sense that it's just too close for comfort. "We've all thought about it to one degree or another," said one attendee.

Dean Randolph said the suicide rate at MIT is about the same as the national average. "We've had 11 enrolled-student suicides in the last 10 years, " he said.

"That's about average, but so what? I take no comfort in that statistic. Our sample is still pretty small and that makes me wary of drawing conclusions. One suicide is too many.

"We live in an extremely divided community. There are some people who feel like we just shouldn't talk about it. They feel that to talk about it is to encourage it or normalize it. Or they feel unqualified to talk about it," said Dean Randolph, who believes we need to talk about it more than we do. And while it often falls to him to discuss the issue, to comfort the family and friends of suicide victims, walking them through the grieving process sometimes for years, he said that he, too, sometimes fears the subject. "My great fear is that someone will leave a note saying, 'I wouldn't have thought to do this if I hadn't heard it discussed,'" he said.

Yet Dean Randolph and Dr. Ross agreed that if someone you know is in danger of committing suicide, the most important preventive action you can take is to reach out, to talk to the person.

"Personal connection is the ultimate antidote to suicide," they said.

"If you see a change in normal habits -- a social person becomes reclusive or a friend stops going to class or meals -- do something," said Dr. Ross.

"If the suspicion [that a friend might be suicidal] has risen to the level of your consciousness," Dr. Ross said, then it's time to take some action. That means talking to the friend privately and tactfully about your concerns, and asking point-blank if he's thinking of harming himself or taking his life.

If the friend admits feeling suicidal, "do empathize, but don't get sucked into that feeling of desperation. Do offer hope for alternatives, but don't give a long list of what's good. Don't lecture. And don't be sworn to secrecy," said Dr. Ross, who urged people to call MIT Medical or a suicide hotline to talk to a professional about their concerns for a friend.

"We don't always see the people who commit suicide in the formal health-care safety net, so we've got to create a wider safety net to recognize the signs," said Dean Randolph.

"Of course, then we run head on into the privacy issue. What gives me the right to ask if someone's considering suicide? How do you break through that barrier?" he said.

What if you ask a friend if she is suicidal and she becomes angry or resentful?

"What we need to do is create a community where people care enough about one another that they don't mind looking foolish" by asking the question, said Dean Randolph.

One person at the IAP session asked if the signs were always obvious.

"After a suicide, the friends and families of the victim don't say, 'I saw this coming. He was very depressed.' Usually they say, 'but he was getting much better; he was actively pursuing his goals,'" said the participant.

"The most cruel irony about many suicides is that when people are at their lowest ebb and don't have much energy, they don't have the wherewithal to think and plan," said Dr. Ross "It's sometimes when they begin to come up from their lowest point that they're more likely to commit suicide." So it's important to keep talking to a friend and make sure they're getting the sustained help they need.

"Suicide can be out of anger, desperation, utter hopelessness, or a gesture gone wrong," Dean Randolph said. "But it's always the last word. The conversation ends."

Denise Brehm

Warning signs of extreme distress that could signal suicidal thoughts

If you see any of these signs in someone you know, talk to them about it, and seek professional advice.

Places to call for help include: On campus -- MIT Medical's Mental Health Service at x3-2916, MIT Medical's Urgent Care at x3-1311, Dean's Office Counseling and Support Services at x3-4861, dean on call and Campus Police at x3-1212, and Nightline (a confidential hotline staffed by students) at x3-8800. Off-campus, call the Samaritans at (617) 247-0220.

For additional information about counseling services at MIT, see web.mit.edu/newsoffice/nr/2000/counseling.html.

- ������Preoccupation with death and dying

- ������Talking about suicide

- ������Preparing for death by writing a will

- ������Giving away prized posessions

- ������Previous suicide attempt

- ������Taking unnecessary risks

- ������Suffering a recent, severe loss

- ������Losing interest in appearance

- ������Increasing use of alcohol or drugs

- ������Trouble eating or sleeping

- ������Withdrawing

- ������Changes in behavior, such as loss of interest in hobbies or work

- ������Publicly grappling with issues of sexual identity

Being there with bells on

Neither snow nor sleet nor nine flights of narrow stairs kept a hardy band from their weekly rehearsal in the bell tower of the Old North Church in Boston's North End. And for IAP, they allowed interested guests to climb the steeple, see the sights Paul Revere saw in 1776 and ring the Old North's eight tower bells.

Group leader Danielle Morse, a junior in earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences, explained how the ropes work the bells and the bells, in their turn, create intricate sounds in precise relation to one another. The group practices change ringing, a style of bell ringing developed for large church bells in Britain several hundred years ago. It does not involve ringing a melody on the bells, but rather permuting the order of sounding the bells according to formal rules called methods.

"I enjoy ringing because it's a challenge mentally and a joy when done correctly," Ms. Morse said.

In the Old North Church, as elsewhere, the bells are hung in a stout frame that allows each one to swing 360 degrees. Each bell, which weighs anywhere from a few hundred pounds to several tons, is attached to a wooden wheel with a hand-made rope. This mechanism is so exquistely balanced that Ruthie McCormack, a fourth-grader in Ms. Morse's group, could control a bell as easily as her parents.

Adding four enthusiastic newcomers to Ms. Morse's usual rehearsal may not have made music, exactly, but it was a marvel to participate in this 400-year-old hobby for celebrating weddings and victories.

IAP change ringing events are scheduled for Thursday, Feb. 1 at 6:30pm and Saturday, Feb. 3 at 10am. For more information, contact Ms. Morse at dmorse@mit.edu . The event was sponsored by the MIT Guild of Bellringers.

Sarah H. Wright

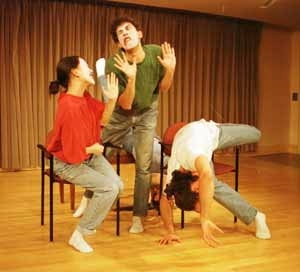

Mime's the word

IAP featured a mime workshop, "Mime for the Imaginationally Intrigued," run by Professor Vladimir Bulovic of electrical engineering and computer science. In "The Family Car Trip," the father has fallen asleep at the wheel and family members are seen in various stages of being slammed awake as the car stops suddenly. They are (left to right) Vanessa Cheung, a junior in biology; Justin Werfel, a graduate student in physics; and Aaron Santos, a senior in physics. Freshman Joia Hertz can just be glimpsed behind the others.

Stratton School for Charm will cap IAP offerings

Charm School, renamed the Stratton School for Charm, will conduct its eighth session on Friday, Feb. 2, the final day of IAP.

More than 30 classes are scheduled for noon-4pm throughout the Stratton Student Center. The curriculum includes "Walking," "E-Mail Etiquette," "Table Manners," "Buttering Up Big Shots" and "How to Tie a Bowtie," all Charm School core courses.

A fashion show in which students and staff will model business and casual attire for the workplace, sponsored by the Office of Career Services and Preprofessional Advising, begins at 4pm in the Student Center lobby.

The day will conclude with commencement ceremonies in the lobby, following the fashion show. Charm School Headmaster Larry G. Benedict, who is also dean for student life, will deliver the keynote address. The CB (bachelor of charm) will be awarded for completing six subjects, the CM for eight and the PhD for 12. No prerequisites, theses or dissertations are required.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on January 31, 2001.