Some 600 Chinese doctors and other health care leaders and an equal number of their U.S. counterparts met at MIT June 24-30 for a conference that provided a rare comparative glimpse into the state of health care in the two countries.

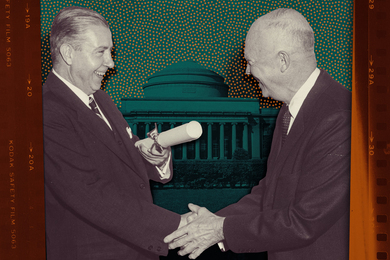

"Health Care, East and West, Moving into the 21st Century," which began with a welcome from Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., was the largest academic medical exchange ever between China and the United States.

"I hope that this conference will result in ways to embrace different [medical] practices and enhance some of our own in doing so," said Kerry, who noted his positive personal experiences with alternative medicine and techniques, such as acupuncture and acupressure.

Kerry, who is chair of the Far East subcommittee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, further emphasized the importance of communication between the United States and China. "This [conference] is the better symbol of how our countries can cooperate and get along rather than building missile defenses and moving in another direction," he said to loud applause.

The conference is designed to allow "U.S. and Chinese physicians to compare the pros and cons of their respective health-care delivery systems and begin to consider common solutions to shared problems," said conference vice chairman Dr. Miles Shore of Harvard Medical International. Chair of the conference program committee was MIT's Nelson Kiang, a specialist in auditory physiology who is the Eaton-Peabody Professor Emeritus at MIT and a professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School.

SIMILARITIES IN PRACTICES

Speakers at a press briefing the first day of the conference attempted to disabuse reporters of the mythological divide between medical communities in the two countries and the notion that Western medicine is always scientific.

Kiang cautioned against "romanticizing" the Chinese tradition and instead offered a very practical reason for some of the differences in medical focus. "As daily life gets full of more and more things, it gets harder to devote time to exercise and relaxation, as many of you are well aware. As Chinese society changes, more and more Chinese will be running around frantically, trying to get their driver's licenses renewed," he said.

When a reporter asked how doctors could incorporate the Chinese framework of prevention into the Western focus on treating illness, Dr. Cao Zeyi, vice president of the Chinese Medical Association, pointed out that disease prevention in China uses both Western and Chinese medicine. Shao Rutai of China's Ministry of Health said the main killer in China is no longer infectious disease, but chronic illness such as cardiovascular disease.

"We're moving toward the Chinese framework and the Chinese are moving toward ours. We can help each other avoid the pitfalls," said Kiang.

"There's a division in both countries between the prevention people and the clinical treatment people," added Shore, who said the payment system in the United States needs to be reorganized. "Payment here is for service, not for prevention. If managed care had been organized the way it should have been," prevention would have been stressed, he said.

When a reporter asked about some Western doctors' refusal to accept acupuncture because it's not proven, some semantic confusion arose.

"Chinese medicine is scientific," said Cao. "When it's tangible, you can't say it's nonscientific. Just like in Western medicine, years ago some of the things we know today were not known. Acupuncture is effective for some diseases, for sure, even though the mechanisms are not so clear to us. For some diseases, the clinical results are very good."

"I never use the terms Western vs. Eastern to mean scientific vs. nonscientific," said Kiang, a research scientist.

"Scientific medicine is justified by the scientific method. Much of what we use in Western hospitals today is not proved by the scientific method. Medicine is still an art; we try different things and what seems to work, we use.

"I would say that neither Chinese nor American medicine is scientific. Both do what they can to relieve suffering and in some cases there is scientific validation," Kiang said. "Science is a very slow process and sick people can't wait."

"Scientific is a goal and an aspiration," said Shore. "We're trying in both countries to add the science."

COST COMPARISONS

"The United States has a lot of strong points in its health care system. But China spends just one-third the medical cost of the United States to care for a population six times as large," said Cao. As a developing country, a large percentage of China's population still lives in rural areas. "We look to the United States to see how it is providing health care in rural areas."

"The problem of delivery of health care to rural areas is not fully solved in either country," said Shore, who was quickly corrected by Kiang, who said with a smile, "Actually, the American way of solving rural health care problems is to eliminate farmers."

In response to a question about drugs vs. herbs, Cao said that Chinese doctors are using more and more Western technologies and pharmaceuticals, which is good for the Chinese people. On the other hand, he said, drugs from foreign companies are increasing medical costs. "I think the U.S. has a similar problem."

"It used to be that economic development preceded health. Now it's the other way around. You can't have economic development without health. Internationally, drugs have made a big difference," said Shore.

Cao said the Chinese are interested in exporting the herbs used in traditional Chinese medicine, if the problems of standardization to meet FDA approval can be overcome, and if the Chinese can find a form of the herbs that will be palatable to Westerners accustomed to pills. "In China, we put raw herbs in a pot and boil them. This is not acceptable to Westerners. We need to reform. For example, put the herbs in powder form. But we don't know if they'll still be effective -- we have doubts."

The conference was sponsored by Johnson & Johnson, the Chinese Medical Association, Harvard Medical School, the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, the Harvard School of Public Health and MIT.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on July 18, 2001.