MIT gravity researchers trying to catch the wave

MIT researchers and colleagues hope to open up the study of the universe by exploring an as-yet-undetected phenomenon: gravity waves.

Though Einstein theorized that gravity must involve the action of a type of wave, there is no direct evidence of gravity waves' existence (there is, however, strong indirect evidence). At an IAP talk last week, Peter Fritschel, a research scientist at the Center for Space Research, described an MIT-Caltech experiment to finally detect and measure them. Key to the work: two very large, exquisitely sensitive measuring instruments at sites in Louisiana and Washington state.

If the researchers succeed in detecting gravity waves they should also be able to learn more about their sources, which include phenomena like supernovae and pairs of stars or black holes. "It will also be a test of [Einstein's theory of] general relativity," said Dr. Fritschel.

The instruments -- interferometers -- will be on line by the end of 2000 with the first data run in 2002. After about 2003, the researchers will install new systems that will allow even greater sensitivity. "That work has already begun," Dr. Fritschel said. Currently the team is building a new lab in Building NW17 where they'll test prototypes for these advanced systems.

Elizabeth Thomson

'Robo-critters' blend nature and technical know-how

A tuna, a lobster and a fish called Wanda are helping MIT researchers apply nature's lessons to man-made technologies and learn more about biological systems.

These three "animals" are actually robots built by engineers in the Department of Ocean Engineering. At an IAP talk on January 29, Professor Michael Triantafyllou described some of this work.

About seven years ago, graduate student David Barrett in Professor Triantafyllou's lab spent roughly 1,000 hours designing a "robotuna." Among other goals, the researchers hoped to learn more about how fish swim and why they are so efficient. "With robotuna, it was as if we had a live tuna available for measuring both the power and forces generated," Professor Triantafyllou said. The work ultimately led to a boat propelled by "flapping foils," which the researchers found was very efficient.

Robotuna, however, was attached to a support structure in the MIT tow tank. So the next step was to develop a free-swimming device that "could lead to more practical applications," Professor Triantafyllou said. Enter Wanda, the robotic pike recently built by graduate student John Kumph. It is controlled by remote control. In other work, research engineer Thomas Consi and colleagues developed a robotic lobster. The goal was to duplicate the crustacean's keen chemical sensing abilities. A robot of this type could be used to study red tides, track fish or locate an underwater oil leak.

Elizabeth Thomson

Contestants create computer 'life' for fun and prizes

Eighty-three students with a flair for programming competed in an IAP event where they created new "life forms" who fought it out for survival.

At the heart of the MIT Programming Challenge, sponsored by MIL 3, Inc., of Washington, DC and the MIT student chapter of the IEEE, was a game called "MITosis." MIL 3 provided a code environment, while contestants provided code fragments describing how their "life forms" behaved within the game, "a challenge where guts and smarts determinewho survives," organizers said.

The life-form competitors tried to maximize their energy by moving about a 100-by-100-square grid, seeking food and avoiding toxins. The life forms could also split into "children," each with half the remaining energy of the parent. Life forms could issue messages during the game to demonstrate bravado, cunning and wit. After a three-hour code implementation period, entries competed in playoff style while the matches were displayed on a large screen in Rm 34-101.

"It was exciting to be back at MIT and see the inventive spirit is alive as ever," said George Cathey (SB '91, SM), director of software development at MIL 3, a developer of advanced software tools for communications network planning and design.

The winners -- sophomore Jason Woolever, juniors John Holmes and Jeffrey Pearlman (all of electrical engineering and computer science) and freshman Daniel Adkins -- claimed prizes supplied by MIL 3, including a former Soviet technology night vision scope, a US Robotics PalmPilot, a Sony 200 CD player and a $300 gift certificate to Tower Records.

Mr. Adkins's entry used a goal-seeking strategy. Instead of expending energy by looking ahead at adjacent squares or avoiding toxins, his life form simply moved in the direction of increasing food scent. "The competion was a great idea and a lot of fun," he said. "I hope it's offered again next year."

Michael Powers (SB '91)

Stars in the lab -- literally

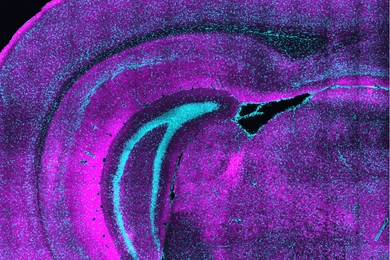

By building a star in the lab, scientists at MIT and Columbia University aim to test an entirely new approach to producing power by nuclear fusion.

The experiment, which will take about three years to construct, focuses on creating -- and confining -- an electrically charged gas, or plasma. Though rare on Earth, plasmas make up 99 percent of the visible matter in the universe, including all the stars in our galaxy.

The traditional way of tackling nuclear fusion on Earth is to confine a plasma with magnetic fields bent into a doughnut shape. The electrically charged plasma particles then move along the magnetic fields like beads on a string. Thus contained, some of the plasma nuclei fuse, releasing energy.

At a recent IAP session, Professor Michael Mauel of Columbia described a new approach. In the Levitated Dipole Experiment, he and MIT research scientist Jay Kesner plan to magnetically levitate a superconducting ring about three feet in diameter in a vacuum chamber about 16 feet in diameter. The plasma will then be confined by following magnetic fields that encircle the floating ring.

If the LDX scientists are successful, "we may have a highly efficient, low-cost way of producing nuclear fusion," said Professor Mauel (SB '78, SM, ScD).

He noted that being asked to give an IAP talk was special to him because "there were two things that profoundly influenced me as an undergrad at MIT: IAP and UROP." His talk was sponsored by the Plasma Science and Fusion Center.

Elizabeth Thomson

Model railroad laying new track

The new quarters for MIT's famed model railroad smell more of sawdust than steam engines. A vast, raw, multilayered system of plywood flats and pine two-by-fours, with gently curving track in some places and gently curving pencil lines awaiting track in others, the model railroad is defintely a work in progress.

Actually, it's a re-work in progress. Ever since the Tech Model Railroad Club's setup was removed from Building 20, club members have been working to design a robust and intelligent computer system requiring very little user intervention to automate the layout, and to rebuild the once-glorious Nickel Plate itself. Hence the IAP course entitled "Hacking a Model Railroad," taught by lifelong model railroad enthusiast Alvar Saenz Otero, a senior in aeronautics and astronautics.

The IAP sessions were intended to make people aware of model railroading and to get them involved in the massive redesign project, Mr. Saenz Otero said. Club members are working hard to display working trains by the end of March with the goal of holding an open house near the end of the spring term.

MIT alumni/ae, mostly former club members, are regularly involved with club operations, mainly contributing their knowledge and experience so that new generations can build a world-class layout. New people at the IAP sessions were interested in building scenery and laying track, all of which must be done by hand, as well as learning about the new control system.

The club will continue to meet on Tuesday nights at 7pm and Saturdays at 5pm.

Sarah H. Wright

Science reporters talk about job

Although a background in science is beneficial for a science journalist, the abilities to tell a good story, get the facts right and understand how scientists work are just as important, according to four science journalists who spoke at "Educating the Public About Science -- Science Journalism," an IAP session sponsored by the Office of Career Services and Preprofessional Advising.

Basic journalism skills that can be acquired from working at a weekly or daily paper are also essential, the panelists said. They told their own stories about how they arrived in science journalism from different directions.

John Benditt, editor-in-chief of Technology Review, considered becoming a doctor and started graduate programs in biophysics and engineering before deciding that more formal education was not for him. At his first journalism job at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, "I learned about the difference between what you know and what you're surmising," he said. He has worked for Scientific American and as a features editor at Science, where he started an on-line service (http://www.nextwave.org) for scientists seeking careers outside academic science.

Melanie Wallace, a senior producer for NOVA at WGBH, had almost earned a PhD in anthropology when she quit to spend three years learning filmmaking. Seeking to make ethnographic documentaries, she worked for NOVA's "Odyssey" series and later worked at Channel 5's medical unit, where she helped produce a popular special on Alzheimer's disease called "Someone I Once Knew." At WGBH, Ms. Wallace works with independent producers around the world to create NOVA documentaries. Her graduate student days gave her a background in how to assess and evaluate research that has proved valuable in her career in science documentary filmmaking, she said.

Tom Paulson, a Knight Fellow in the MIT program for science journalists and a reporter at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, majored in chemistry and considered a career in medicine, but then became a carpenter and built houses while contributing short environmental pieces to an Audubon Society newsletter.

After obtaining a master's degree in science journalism from Johns Hopkins University, he worked for a small paper in Idaho before becoming a science writer for the Post-Intelligencer. His favorite stories have been those that ask deeper questions about how science works in society. "There's a lot of science writing, but not a lot of science reporting," he said.

David Baron majored in geology and physics at Yale, but he also ran the college radio station and knew his dream job would be science reporter for National Public Radio. He interned at NPR and later freelanced at its Boston affiliate, WBUR. When the station created a science reporter position for him, he occasionally supplied segments to NPR.

Two years ago, he realized his dream and became a staff reporter for NPR, where he has covered medicine, astronomy, technology and now environmental issues. "The question for me is where do I go next?" he said. "This is the job I always wanted."

Deborah Halber

Nuclear power key to cutting CO2

Nuclear power will be an important part of the energy mix if countries hope to meet the carbon dioxide emissions goals of last year's climate-change conference in Kyoto, Japan, said a member of a presidential task force on energy at a January 26 IAP talk.

"It seems inevitable that we have to look at [nuclear] fission," said John Ahearne of Duke University. Dr. Ahearne was part of a panel of experts tapped by the White House last year to review the nation's energy research and development program.

At the Kyoto conference, participants set a goal of reducing emissions of the greenhouse gas CO2 to below 1990 levels. "That is not a trivial commitment," Dr. Ahearne said. "It will be very, very difficult to achieve."

He noted that only one country -- France -- has made significant headway in decreasing CO2 emissions, and that is primarily due to its use of nuclear power. The country gets 77.4 percent of its electricity from this energy source. (Lithuania is first with 83.4 percent; the US trails at 22 percent.)

The panel recommended increasing the federal R&D budget for nuclear fission from $42 million in 1997 to $119 million in 2003. It also recommended increasing funds for R&D on renewable energy sources (e.g., wind and solar) and for nuclear fusion. In contrast, it recommended "essentially little change" in monies for fossil-fuel research ($340 million in 1998 to $371 million in 2003).

"Only nuclear power and renewables can significantly reduce carbon dioxide emissions," Dr. Ahearne said.

President Charles Vest and Professor Jefferson W. Tester were also on the energy panel, which was created under the auspices of the President's Committee of Advisors on Science and Technology. The complete panel report is available on the Web, or call (202) 456-6100.

Elizabeth Thomson

Looking elsewhere to understand the origin of life on Earth

With frigid temperatures, no water or air and a continual bombardment of ultraviolet light, Mars is a singularly bad choice for a vacation spot.

Yet there is increasing evidence that Mars once had liquid water. With that plus a source of energy, the red planet had just as much chance of fostering life as did Earth, said Claude R. Canizares, the Bruno Rossi Professor of Physics and director of the Center for Space Research. He spoke at a January 27 session entitled "From the Origin of the Universe to the Origin of Life."

While not everybody believes the contention of some scientists that meteorites from Mars contain fossils of microorganisms, these rocks do provide further evidence that the planet was once home to liquid water--an essential ingredient for life.

The last decade has provided scientists with startling evidence that organisms can exist and flourish in conditions once thought incompatible with life. From hot springs at Yellowstone National Park, where microorganisms metabolize sulphur instead of oxygen, to deep-ocean hydrothermal vents that teem with microorganisms that live happily in temperatures as high as 113��������� Celsius, life can and does exist in extreme conditions.

Life seems to have emerged on Earth very soon after the creation of the planet. Relatively evolved life forms have been fossilized in rocks found in Antarctica that are three and a half billion years old, Professor Canizares said.

For its first 500 million years, the Earth was bombarded by debris from solar nebulae that would have vaporized any budding life forms. But "as soon as the Earth stopped being an inferno, life appeared to pop up," he said.

Meanwhile, scientists are looking to information from space probes and huge space telescopes to bolster our knowledge of the building blocks of biotic activity and the birth of galaxies and chemical elements. They hope to find other planetary systems beyond ours and planets being formed. They hope to determine the scope of the sun's influence in outer space and to learn more about the size, age and mean density of the universe.

In the search for information on the origins of life, scientists are looking, among other places, to Europa, one of Jupiter's moons. Europa has a fractured, icy crust that may top a liquid ocean. "Who knows what lurks beneath that icy surface?" he said.

Although solar energy wouldn't play a big part in Europa's environment, he said the tidal friction caused by the orbiting mass of the mother planet may provide a source of energy.

Last year's White House conference that brought together biologists and physicists left both groups exhilarated about the recent expansion of understanding of the origins of life.

"We are now getting scientific answers to questions that once elicited only philosophical theorizing," Professor Canizares said.

Deborah Halber

Rice discusses changes at MIT

In the future, the work environment at MIT may become more open and flexible. While technology will continue to play an important role, it can never replace the human element, said Joan F. Rice, vice president for human resources, at an IAP session entitled "Current Trends in Our Workplace."

"Not all technology adds value," she said. "We must use technology effectively." Communication is key to improving the workplace: "the root cause of at least 90 percent of workplace issues is poor communication."

In her 25 years at MIT, Ms. Rice said she has seen a considerable amount of change. Among the changes slated for MIT's future are increasing the diversity of the staff, paying more attention to attracting and keeping qualified employees, better communication across the board, and greater flexibility in work schedules, including more telecommuting.

Change in some quarters has been in response to an increasing perception that institutions of higher education need to be more financially accountable to the public, Ms. Rice said.

The Institute also needs to acknowledge that as one of the biggest employers in the area, it is competing with industry for competent, qualified workers, she said. Because universities typically cannot pay as well as industry, "we will have to find ways for people to really want to be here."

MIT may be able to take cues from industry in building an environment in which people enjoy their work and see room for advancement. "We should try to make this the best place for students to study and faculty and research people to do their work," she said.

Deborah Halber

Work, personal life don't need to conflict

Some companies are surprised to find that making life easier for employees also increases productivity, said Lotte L. Bailyn, the T Wilson (1953) Professor of Management at the Sloan School, at an IAP session on "Integrating the Demands of Work with Other Life."

"Everyone has a personal life," she said. But the current perception that employees' personal lives create a problem for organizations places work and personal lives in adversarial roles.

Recent efforts to make corporations "family friendly" have concentrated on the needs of mothers with young children. Professor Bailyn said these efforts can backfire when other employees resent them. A benefit like flexible schedules should be available to all employees, she said.

In her research, Professor Bailyn explores the underlying assumptions that have made the business needs of the company and the personal needs of workers into two sometimes conflicting entities. For instance, long hours create the appearance that employees are getting a lot done. But long hours can lead to mistakes because workers can't maintain the same rate of effectiveness over a long time span.

When employees' legitimate personal concerns were brought into the work environment, workers often reported greater job satisfaction, had lower rates of absenteeism and increased efficiency, Professor Bailyn said.

"We try to introduce changes both to help get the work done and make it easier for people to integrate work with their personal lives," she said. "It turns out that if you make changes in work practices that make people's lives more livable, you also improve the effectiveness of the work."

Deborah Halber

Personal views offered on job changes

Three MIT employees with quite different perspectives on working at MIT discussed at a January 30 IAP session how they have managed--and even benefited from--quite drastic changes in their work lives.

Judith Stein, who has worked at MIT for 19 years, is administrative officer of both the anthropology program and the Program in Science, Technology, and Society. She experienced a major upheaval here four years ago, resulting in her working in two separate physical spaces, systems and subcultures simultaneously, and was frank about the personal toll it took.

"I was not gracious about the change. I spent six months kicking and screaming outside and doing the same thing, more professionally, inside MIT," she recalled. Yet Ms. Stein also set the generally upbeat tone of the meeting when she went on to reflect, "I can now see some positives. I have had to become more flexible. I have had to let go, to accept human error and accept that, with the two roles I have, I can't perform at the level I used to."

Ms. Stein also speculated on the changing nature of administrative officers' jobs, noting how departmental loyalty is yielding to institutional loyalty as individuals no longer work in "steady-state, responsibility-oriented" roles.

As chair of the Administrative Advisory Committee, Ms. Stein recommended the support and "reality-checking" of a smaller group. "I can ask, 'Am I nuts to be so stressed out?' And we can ask, 'How can we make these changes work best?'"

Linda Stantial, career planning director at the Sloan School Development Office, contrasted her own experience with Ms. Stein's to illustrate how some stressors persist, regardless of who initiates a change, while others are eased.

"Everybody's having to do more with less," said Ms. Stantial. "That's typical of the world. So is the sense of not being able to meet professional and personal standards."

"Participation is key" in helping to reduce the stress accompanying change, she said. She described how Sloan School Dean Glen Urban invited that community to share in deciding whether to lay off people or generate revenue by expanding the master's program. She also cited her own involvement with The Change Initiative, a grassroots group within Sloan whose mission was to improve the quality of work life and employee effectiveness at the School.

In the face of organizational change, Ms. Stantial coordinated a broad-based volunteer effort to build a stronger sense of community, enhance communication and improve professional development opportunities at Sloan. And she received professional and financial support for devoting 20 percent of her work time to helping chart a course through challenging times for the Sloan community.

Jeff Pankin "happens to work for a progressive manager," he said, going on to credit that manager, Jeanne Cavanaugh, for the job he has today. He works half-time in Information Systems and half-time on the Performance, Consulting and Training Team.

"Two half-time jobs always add up to more than one full-time job," said Mr. Pankin, who was quick to say how pleased he was with opportunities he's had to express interest in new areas of work at MIT.

Sarah H. Wright

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on February 4, 1998.