They came to praise the CM5. And to bury it.

After one final chess game, Albert Vezza, former associate director of the Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS), flicked the switches on the super-computer on July 16, shutting it down after four years of memorable service. The red lights flickered for the final time at 5:15pm while a VCR played the computer HAL's deathbed soliloquy from the film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

"In my native Greece, we mourn at funerals, but we also drink a lot," LCS Director Michael L. Dertouzos told about 60 faculty, scientists, staff, students and guests who gathered for a good-bye party at the laboratory.

CM5, officially a 128-processor Connection Machine Model CM5, was acquired from Thinking Machines Corp. in 1993. It was the 17th most powerful computer in the world at the time, with more power than all of Project Athena. At shutdown, it still ranked 497th.

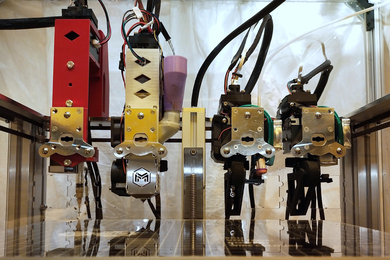

The 6-by-3-by-6-foot CM5, the computer in the movie Jurassic Park, was retired to make room for new equipment. It will be placed in storage and its future is uncertain. "There was some talk of making plaques from it and some talk of selling it," said Alan Edelman, assistant professor of applied mathematics. So far, no one has made an acceptable offer.

The CM5 was the flagship of Project Scout, a collaborative effort that brought together architects, programmers and users from many departments and other institutions, including Boston University and Harvard, with Mr. Vezza as the principal investigator.

"It captured a lot of our imagination," said Professor Dertouzos. "It was like mixing a big salad."

The mix required specialists accustomed to working within their own disciplines to coordinate and communicate with people from other fields. The excitement -- and the productivity and innovation -- were contagious. "It was almost like a dating service with the big machine sitting in the middle," said Dr. Thomas J. Greene, Project Scout's manager.

The project produced breakthroughs in a variety of fields, including numerical algorithms for protein folding; moldeing of animal and plant viruses, oceans and backflow contamination of ion thrusters onto spacecraft; and planning radiosurgery of brain tumors.

The CM5 also drove the MIT chess programs *Socrates and Cilkchess, when they competed with great success on the computer chess circuit. Trophies from several tournaments were displayed next to the machine during the shutdown ceremonies.

During a supercomputer conference in Washington in 1994, Charles Leiserson, professor of computer science and engineering and the LCS's chess expert, offered a free *Socrates T-shirt to anyone who could last three minutes playing chess against the CM5 (computer matches usually take about five minutes). Nobody could. The time was reduced to two minutes. Still no winners. The T-shirts were then distributed to anyone who competed against the CM5, since nobody wanted to carry them back to Cambridge.

The CM5 was blessed with good fortune from the beginning. In its first chess tournament, the programmers inadvertently introduced a bug into the timing device that should have ended the competition for the MIT team. But somehow, the programmers had simultaneously introduced a second bug which neutralized the first one. The CM5 went on to finish third in the 1994 North American Computer Chess championships at Cape May, NJ. "That was a stroke of luck that we never fully understood," said Professor Leiserson.

In its final game, the CM5, running the *Socrates chess program, was matched against Cilkchess, a more recent program running on a modern eight-processor Sun Microsystems computer. Fittingly, the CM5 was the winner, even though its technology was two computer generations older. "It was definitely not rigged," said Don Dailey, who wrote both programs, his grin clearly an indication that the result pleased him.

The farewell party, as much celebration as wake, was organized by Professors Leiserson and Edelman, both Thinking Machines alumni. Besides Professor Dertouzos, Mr. Vezza and Dr. Greene, speakers included maintenance manager Scot Blomquist (toting his trusty screwdriver); John Negele, the William A. Coolidge Professor of Physics; and Arvind, the Charles W. and Jennifer C. Johnson Professor of Computer Science and Engineering.

"So many people loved this machine that it didn't seem right to shut it off without a proper sendoff," said Professor Edelman. That included a final message, hacked by Professor Edelman, which said: "No! Mr. Vezza, no!" The lights went out on schedule.

Before the party, Professor Leiserson wrote the CM5's vital statistics on a whiteboard in the LCS lounge area:

128 processors, each with 4 vector units.

* "Fat Free" interconnect

* 16 gigaflops peak performance

* 4 gigabytes of main memory

* 36 gigabytes of disk storage

* And nice lights!

Someone added a footnote, perhaps the appropriate inscription for the tombstone of a beloved thinking machine: "Wicked awesome."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on August 13, 1997.