Many students who participate in the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) have plenty of classroom knowledge in their fields but little lab research experience. The Department of Ocean Engineering began a program this summer to give 10 UROPers practical training in how to begin, complete and report on a research project.

"We get students who are really bright, who want to do lab research, but who think they don't know how," said Thomas Consi, research engineer and instructor in ocean engineering, who developed the Summer Workshop for Undergraduate Research based on a similar program he ran for MIT Sea Grant. "I ask about their hobbies and it turns out that a lot of them can do quite a bit. They just don't attach enough value to it. Or sometimes they just don't know how to get started with research."

He and the four other research advisors take these students -- some of them new to lab work and some who are experienced UROPers -- through a program focused on research procedure, lab sociology and oral and written communications. The basic training, dispensed in a one-week "common training" course at the beginning of the summer, teaches safety and lab procedures and provides instruction in using lab tools, as well as in the ethics and sociology of group research. Dr. Consi believes that these sociological aspects are key to a smooth-running lab.

"We teach them how to criticize constructively. That goes a long way in helping a career in research. And we hold a weekly lab meeting where everyone gives an update on his or her work. I've noticed in labs that people can get pretty isolated, so by knowing what everyone is doing, they can help each other. For instance, when our autonomous shark-tracking boat needed a test run, the students from other projects all pitched in to help," said Dr. Consi.

The shark boat is just one of the success stories of the summer's research. Its student creators (Brendan Donovan, a senior in mechanical engineering; Matt Graham, a senior in physics, and Linda Kiley, a junior in ocean engineering) and faculty advisors (Dr. Consi and Clifford Goudey, a marine engineer at MIT Sea Grant) all hope that it will take a dip in the ocean early next fall to do some real-world research.

In a test run in the Charles River early in the summer, they made one important discovery they could not have made in the lab -- the boat's color was wrong.

"It was forest green," Ms. Kiley said. "We realized it matched the algae in the Charles."

"We had some close calls with large boats not noticing it," Mr. Donovan said.

The boat, now painted fluorescent orange, may lack subtlety in appearance, but it aspires to stealth in tracking tagged marine animals, a characteristic missing from current methods.

"It's very quiet. One problem that trackers have now is boat noise. You can end up chasing fish around instead of tracking natural movement. With our boat, there'll be no gas engine to disturb the fish," said Mr. Graham, who actually began work on the shark boat last fall as a UROP.

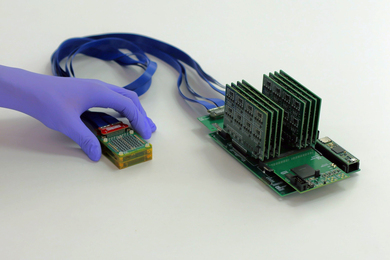

The shark boat, a kayak hull fitted with a keel, propeller and hydrophone (an underwater microphone), runs on two batteries about the size of car batteries inside the kayak's cockpit with the electronics. It is designed to be launched from a larger boat and left to follow the tagged fish. The hydrophone picks up the tagged animals' signal and sends it to the computer, which then 'decides' on the right direction to steer the boat.

"We hope to publish a paper on this. According to an editor at one of the journals, this is the farthest anyone has gone in tracking fish. Most researchers are doing it 'by hand,' and this is a huge leap for them," said Mr. Graham.

Right now, trackers have to listen for the hydrophone's signal and follow it themselves. "They go out on a gas engine boat with a hydrophone on a stick and move the boat around to listen for the tagged animals. They do this sometimes 48 hours at a stretch," Dr. Consi said about the current state of tracking technology. "Ours will work autonomously."

Another autonomous vehicle also figured prominently in the group's summer research. This one is named Autolycus, after the mythological Hermes's son, and is built in part from the underwater autonomous vehicle called Hermes.

"We were given a box of Hermes's parts and told to revamp it. Instead we rebuilt it and changed its purpose. It's now a great teaching tool because it's modular and really versatile," said Sheri Cheng, who worked with lab partner Ian Ingram (both are juniors in ocean engineering).

Ms. Cheng and Mr. Ingram, who were advised by Dr. Consi and John Leonard, assistant professor of marine robotics, hope that Autolycus, which looks like a four-foot rocket made of clear tubing, will be able to swim underwater on its own. The tube will house the electronics necessary to perform numerous as-yet-to-be-determined underwater experiments. To make it easier to add new experiments quickly, Autolycus's pieces fit together like Lego pieces. "New stuff is the crux of Autolycus," Mr. Ingram said.

The summer workshop also provided a taste of the wider world of ocean engineering through field trips and guest speakers. Students had a behind-the-scenes tour of the New England Aquarium as well as visits to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's Deep Submergence Laboratory and the International Model Submarine Regatta in Groton, CT. The four guest speakers included Martin Klein (SB '62), who talked about his attempts to find the Loch Ness Monster using sonar.

Another focus of the workshop was teaching students how to communicate their work in layman's terms. "Students will often just start talking as if you know what they're talking about," said Dr. Consi. During the summer's weekly lab meetings, the students learned to present their week's work in a way that everyone present could follow. At the end of the summer, the group met for a final four-hour symposium of formal research presentations, complete with slides and refreshments.

"It's a little scary, and preparing for it took some time, but it will be nice to have completed it," said Ms. Kiley, summing up her feelings about the end of the summer's research.

Referring to the newly minted pieces of Autolycus, lying on his lab table waiting for assembly, Mr. Ingram said, "This is the high point of the summer."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on August 27, 1997.