Within the last three years, two types of gene-based male infertility have been identified as researchers investigate genetic links to a problem that affects one in six American couples, said Dr. David Page, an associate professor of biology at MIT and member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research.

One case involves a gene that causes cystic fibrosis, a deadly disease that clogs the lungs and also results in boys being born without the vas deferens, which connects the testes to the penis. As a result, sperm cannot get out of the body and the male is infertile. The second situation is a spontaneous mutation on part of the Y chromosome which results in males having a sperm count near zero.

Both cases are generating much interest in both the scientific and medical communities, said Professor Page, a mammalian geneticist who gave an IAP talk entitled "The Genetics of Infertility."

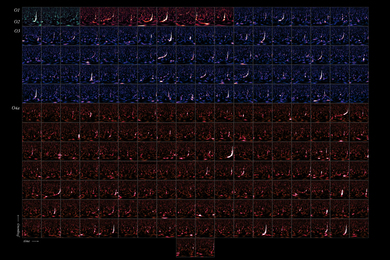

Professor Page has for years studied how an embryo becomes male or female; more recently, he has focused on infertility. In 1992, his laboratory mapped and cloned the Y, or male, chromosome, which is leading to new understandings of sex chromosome disorders, including infertility.

Infertility is difficult to define and it isn't necessarily an all-or-nothing proposition, said Professor Page. For example, most physicians define infertility as the inability of a couple to conceive after one year of unprotected intercourse. However, as the second and third years go by, some of those couples may eventually conceive a baby.

Even though infertility is a common problem, scientific research has not focused on that as much as on more dangerous diseases like cancer or high blood pressure. Part of the reason, he said, is that infertility is a "secret" disease that people hesitate to share with family and friends.

Professor Page said a few infertility cases have been linked to genetics. In one case, scientists have found a link between the cystic fibrosis (CF) gene and infertility in males who do not have CF. Some 50,000 American males, or about 1 in 2,500, are born without a vas deferens. Even though that population of men does not develop CF, virtually all of them do have mutations of the CF gene, he said.

"This was one of the first cases for a genetic basis of infertility," Professor Page explained.

There is a treatment for such infertility: physicians can use a needle to remove sperm from the man and unite it with multiple eggs from a woman."This has been done with some couples, but it is technically difficult, expensive and trying for the couples," he said.

The multiple embryos are then screened for CF. If the mother carries a CF gene mutation, the child has a 50 percent chance of getting CF. The condition is an autosomal recessive disease which results when each parent is a carrier, having one "good" and one "bad" copy of a CF gene. Children get CF if each parent passes down the defective CF gene to them.

Another genetic link to infertility was found in men with near-zero sperm counts, a condition that affects about one in 1,000 men. In such cases, the man may actually make a few sperm. Of these zero-sperm-count men, about one in eight can attribute their infertility to a spontaneous mutation of a weak part of the Y chromosome. So the infertility is not actually inherited from the man's parents--it is a new genetic mutation.

A man who has an SRY gene (the sex-determining gene on one end of the Y chromosome) but who lacks azoospermeo factor (AZF) on the other end of the Y chromosome will not be able to produce sperm, Professor Page said.

"So how do you have a family with infertility if the boy gets his Y chromosome from his father and the father is fertile?" asked Professor Page. "These are new mutations where some parts of the genome are in 'bad neighborhoods' or weak parts of the genome. So a genetic disease starts in a fresh mutation. Like a lightning strike, it hits an unstable part of the Y chromosome."

Professor Page pointed to an interesting ethical dilemma in such azoospermic men: if physicians attempt to inject a woman with the few sperm found in her mate, they actually will be taking an uninheritable disease and making it heritable.

To date, only 50,000 American men have been found to be infertile because they were born without a vas deferens, and another 15,000 have azoospermic deletions in part of their Y chromosomes. But Professor Page predicted that over the next several years, we will see many more examples of gene-based infertility.

"So we're just beginning to get at the edge of this problem," he said, adding that environmental factors still are a major focus of study. "It remains to be seen whether genetic defects cause 10 percent or 90 percent of the problems in infertility."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on February 5, 1997.