A new human-powered hydrofoil boat designed and built at MIT may break the world speed record set by an MIT craft two years ago.

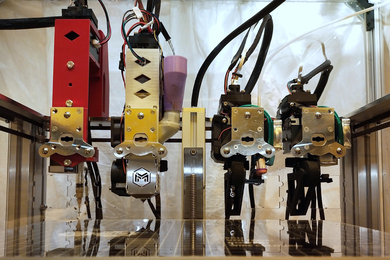

The 17-foot craft, which is unofficially known as Skeeter, is designed around an ordinary one-person kayak hull. It's powered by a driver using a bicycle-like arrangement of pedals, cog and chain to turn a shaft that ends in an eight-inch underwater propeller situated behind the raised seat.

Involved in the project are Aeronautics and Astronautics Associate Professor Mark Drela (who was faculty advisor for the team that created Daedalus, the human-powered aircraft that made the historic flight between two Greek islands in 1988); Sepehr Kiani, who is studying for his master's degree in mechanical engineering; mechanical engineering doctoral candidate Matthew Wall and UROP student Fred Ackerman. The faculty advisor is David Gordon Wilson, professor of mechanical engineering. Design began in December 1992 and construction in the late spring of this year, Mr. Kiani said.

In 1991, the hydrofoil Decavitator broke the world speed mark for human-powered watercraft when Professor Drela pedaled the craft at 18.5 knots (21.3 miles an hour) over a 110-yard course, breaking the previous mark of 17.6 miles an hour. Dava J. Newman, then a graduate student in aeronautics and astronautics, established a women's speed record of 13.1 miles an hour in the craft's intermediate-speed configuration.

When at rest, the new hydrofoil, like the Decavitator, sits with its hull in the water like an ordinary kayak, Mr. Kiani explained. After it begins moving, the driver can operate struts behind the seat that control underwater wing-like foils.

"When you get up enough speed, you can change the angle and get some lift," he said. "The hull will come up slowly [out of the water] on its own." The boat then cruises over the water with only the foils making contact with the surface, thus greatly reducing the drag that ordinary boats experience. Rowing or paddling also involves a loss of energy between the rower and the water in which he or she is moving, Mr. Kiani added. "It's a lot more efficient with a propellor to get the energy to the water," he said.

Another foil in the bow is mounted just behind the skimmers, a pair of curved pieces of fiberglass designed by aeonautics and astronautics graduate student Tom Washington that pivot up and down as the boat encounters waves. The devices set the bow's height and act as something of a shock absorber by allowing it to "follow" the larger waves and canceling out the smaller waves, Mr. Kiani said.

The Decavitator had a different design whereby the propeller was atop the hull behind the seat and was eight feet long, Mr. Kiani said. The earlier craft also had two joined hulls.

With a physically fit 140-pound man pedaling the new hydrofoil (which will weigh 40-50 pounds when complete), it should be able to cruise for several hours at 12 to 13 knots (about 15 miles an hour) and attain a top speed of 15 to 16 knots, or more than 18 miles an hour, Mr. Kiani said. Will it be able to break the Decavitator's speed record? "On paper, we think it has the potential to do that," he said.

The hydrofoil, which was built in a lab in the basement of Bldg 7, first hit the Charles River for testing about two weeks ago. The team is using information from that trial to iron out any design kinks. Some modifications have already been made; earlier in the project, the drive train featured a belt and pulley rather than a chain and cog, but that design was abandoned after the belt repeatedly jumped off the pulley during tests in a water tank. It's also less efficient than the current design, Mr. Kiani said.

Team members gave the hydrofoil its first public performance its first public last weekend, when a Dutch television crew came to tape a segment on the project for a science show. If all goes well farther down the line, there could be patents, marketing and perhaps even a new sport, Mr. Kiani said.

A version of this article appeared in the October 27, 1993 issue of MIT Tech Talk (Volume 38, Number 11).