An MIT professor had a close call this summer when the plane he was piloting went into the ocean off Groton, Conn., but he's back in the air, already having upgraded his skills.

Dr. William J. Dally, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science whose research is in parallel computer architecture, was flying from Hanscom Field in Bedford, Mass., to Farmingdale on Long Island on Sunday, Aug. 9, when things began to go wrong in his single-engine Cessna 210.

He was about 20 miles southwest of Norwich, Conn., 6,000 feet over the coastline in storm clouds, when he saw his oil temperature begin to climb, a sign that he was losing oil.

As all pilots know, crashes tend to occur because of a combination of circumstances.

In this case, the bad weather was an important factor. It was still light at about 6pm and, under visual flight rules, Professor Dally would have headed on a direct route to the nearest airport in Groton-New London about 10 miles away. Because he was in clouds flying on instruments, however, he had to ask an air traffic controller for clearance to the airport.

The route the controller gave for intersecting the airport's instrument landing system beacon actually took him away from the airport, heading south out over Long Island Sound. His request for a more direct heading was turned down.

In retrospect, Professor Dally realizes he made a mistake at this point.

"I should have declared an emergency," he said, "and then I could have had whatever route I wanted." But he still thought that the problem might be a faulty oil temperature gauge, so he hesitated.

Minutes later, having come down to about 3,000 feet and now headed for the airport, his engine seized about eight miles from the field. He described the sound to a reporter for the New London newspaper as "a lot of softballs kicking around in an oil drum."

Knowing he couldn't reach the airport, he set up a glide pattern and told the controller he was heading for a crash landing in the sound.

He came out of the clouds about 400 feet above the water, with rain still falling heavily, levelled off above the three-foot swells and smacked down at about 70 miles per hour some two miles short of the airport. The plane's nose immediately dipped, putting his head under water as the plane began to sink-which would take just 20 seconds.

Professor Dally was wearing his seatbelt, but the seat was not equipped with a shoulder harness, so his head had slammed into the steering yoke, breaking his nose. When he tried to open the door, the water pressure held it tight, but he was able to push out a window that normally opens only four inches by breaking the stop. He slithered through, taking a seat cushion with him as a float.

In the 60-degree water, he tried swimming to a nearby buoy but the current pushed him back. Then he set out for shore. "I'm a strong swimmer and I think I would have made it, but I was worried because the water was very cold," he said.

Several times, Coast Guard boats searching for him went by when they couldn't hear his shouts. Finally, a man and woman in a sailboat, also looking for him, heard his cries and took him aboard. They were using an auxiliary motor, but it was quieter than the Coast Guard engines.

Professor Dally's plane isn't a navigational hazard and will remain at the bottom of the sound. "If I had been killed, they would have raised it to try to find out what went wrong," he said wryly, "but because I lived to tell them, it will stay there." Professor Dally said the cost to bring it up himself would be prohibitive.

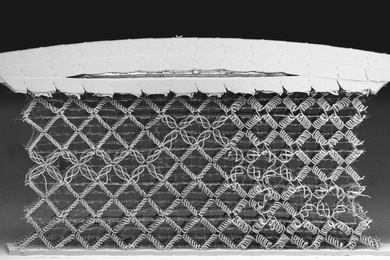

He isn't certain, of course, what caused the oil leak but he had the propeller rebuilt two flying hours before the accident and he suspects it's tied to that-perhaps along the lines of a loose seal in the hub.

The plane also was underinsured, he said, because he always assumed that any accident serious enough to destroy the craft would also kill him-a happy miscalculation, as it turned out, except for the money lost.

The 32-year-old professor said the accident was his first serious incident in 11 years of flying-and he isn't about to let it stop him.

He's now looking for a twin-engine plane, however, to get that extra measure of safety that comes with a second engine-particularly for the long distances he covers in consulting for the Cray Computing company and government agencies. He often flies to Wisconsin and Washington, D.C., for example, and on the day of the crash was going to Farmingdale to pick up a Columbia University professor for a flight to Norfolk, Va.

To be ready for the new plane, he recently passed his certification test flight for a multi-engine license.

"Flying is still probably the safest form of transportation," he said. A resident of Framingham, where he lives with his wife and two children, he added, "I feel safer in a plane than in a car on the Massachusetts Turnpike, which I drive every day."

A version of this article appeared in the September 30, 1992 issue of MIT Tech Talk (Volume 37, Number 8).