Students, activists, and MIT Police leaders participated in a public forum about police practices and communities of color on Feb. 4, sharing perspectives about a civic issue of high national importance.

Nationally, policing is a “fraught and complicated story of biases both known and unknown,” said John Dozier, MIT’s Institute community and equity officer, during introductory remarks at the event, titled "Reimagining Public Safety" and organized by MIT's Black Graduate Student Association.

Citing multiple extensive studies about law enforcement and the justice system, Dozier noted that “people of color are overrepresented across all stages of the criminal justice system relative to their share of the population,” while Black and Latino defendents are more likely to be convicted and serve long prison sentences. Students on campus have “justifiable concerns about this national picture,” he observed.

One purpose of the forum, Dozier noted, was to ask: “How exactly does MIT fit into this? … As an Institute community of creative problem solvers, what can we do to solve this? We don’t know the answers to those questions, but I think that today puts us on a path toward answers.”

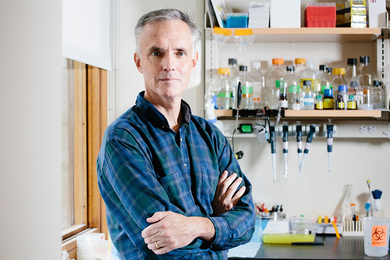

Dozier commended MIT Chief of Police John DiFava for participating in the forum along with Deputy Chief Steven DeMarco, at the request of students.

“I have tremendous respect for this decision, and for John himself,” Dozier said. “I also know that the relationship between our police force and our entire community matters to him, as it does to me.”

In their remarks, DiFava and DeMarco noted that the MIT Police serve the community in a wide range of roles, with law enforcement matters representing a small share of the calls the department receives. It is also an entirely professionally trained but independent department, he emphasized.

“We stand alone. I work for the Institute; we are not beholden or dependent on any outside police agency,” DiFava said.

“We have a long history in quality of service for our community here,” DeMarco said. “We have a good story to tell. We really have addressed very well the needs, the values, and the mission of this community.”

He added: “Can we improve? Absolutely. Do we want to improve? Absolutely. We need to look introspectively, and listen, and understand what the community needs are.”

Sharing experiences

The forum also spotlighted the accounts of two MIT students who described campus incidents that left them deeply shaken.

Omar Rutledge, a PhD candidate in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, recounted a pair of times within the last two academic years when he was sitting in his car on campus, about to leave — once in the Westgate parking lot, once in the Albany Street garage — and someone called the police to report suspicious activity. Both times, multiple MIT Police vehicles arrived at the scene, verified Rutledge’s MIT identification card and driver’s license, then left.

“Although I had done nothing wrong, my heart was pounding through my chest,” said Rutledge about the first incident, in the Westgate lot, emphasizing the feeling of alienation that resulted. “When I think of what it means to be a student at MIT, I will never forget what it felt like when it became apparent that I did not fit the expectation of what a student at MIT is supposed to look like. … That’s the message I took out of the experience: I do not belong at MIT.”

Rutledge, an Iraq War veteran, said that during the Albany Street incident, “I didn’t feel very safe at the moment. … As a combat veteran it is also quite triggering to me to have several armed people surrounding me for no obvious reason. All I was doing was trying to go home.”

Ultimately, he suggested, “Instead of fostering a culture of fear with messages like ‘See something, say something,’ let’s try to find better ways to foster a culture of community.”

Candace Ross is a PhD student in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and a graduate resident assistant in Chocolate City, an undergraduate community consisting predominantly of Black men. She recounted an incident from February 2020 in which MIT Police responded to a call that was a false allegation about violent activity, and entered the residence hall, searching the rooms of two students. The experience shocked and frightened the students living there.

“At MIT, and outside our walls, calls to police about Black people often result in Black trauma,” Ross said. “These are really the stories to think about as we navigate how to truly protect all of our students in our MIT community.”

“Prisons do not disappear social problems”

The event’s keynote speaker, Trina Reynolds-Tyler, director of data at the Invisible Institute — a Chicago-based nonprofit focused on police reform — told another kind of story about the relationship between people of color and campus policing, based on her own undergraduate experiences in the state of Colorado.

When Reynolds-Tyler’s visiting boyfriend became violent in her campus dorm, she subdued her boyfriend and ended the relationship instantly — but thought calling law enforcement would have created greater problems.

“I wanted my community to support me, and not dispose of him at the same time,” Reynolds-Tyler said.

The larger issue, Reynolds-Tyler noted, while focusing much of her talk on law-enforcement abuses in Chicago, is unusually punitive treatment toward Black people: “Why do we continue to invest in systems that inherently harm Black people and people of color? … Prisons do not disappear social problems. They disappear human beings.”

Reynolds-Tyler also moderated a panel discussion among activists, about the national “defund the police” movement. The panel consisted of Alex Y. Ding, co-director of organizing at Dissenters, a national anti-militarism group, and leader of the University Of Chicago’s #CareNotCops initiative; Nino Brown, a Boston public school teacher and organizer with the ANSWER coalition; and Ashley Ransby-Sporn, co-director of organizing at Dissenters and a founding member of BYP100 (Black Youth Project 100), an organization focused on justice and freedom for Black people.

MIT students moderating the event were Ufuoma Ovienmhada, co-president of the Black Graduate Student Association (BGSA) and a PhD student in both the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro) and the Media Lab; Will Jackson, co-president of the BGSA and an MBA student at the MIT Sloan School of Management; and Chelsea Onyeador, political action chair of the Black Graduate Student Association and a PhD student in AeroAstro. The BGSA played a lead role in organizing the event.

Onyeador discussed the Support Black Lives at MIT petition — launched last summer by the Black Graduate Student Association, and co-sponsored by the Black Student Union — which has since gained over 5,000 signatures from the community and beyond. The petition focuses on an Institute-wide strategic plan to address systemic racism, and community safety issues.

“We wrote the petition because to us it was really important, while we were looking at these external sources of racism that lead to the extrajudicial murder of unarmed Black folks, that we also take a look at our own community and the racism that exists here,” Onyeador said.

Thursday’s forum was part of an ongoing campus discussion about equity, diversity, and public safety. The massive national protests of 2020, touched off by the killing of George Floyd in late May, have brought renewed attention to policing practices and community relations. The Institute Community and Equity Office is also developing a comprehensive strategic action plan for equity and diversity across MIT.

The event was sponsored by the MIT Black Graduate Student Association; MIT’s Institute Community and Equity Office; the MIT Police; the Office of Graduate Education; the Office of Multicultural Programming; Grad Students for a Healthy MIT; the LatinX Graduate Student Association; the Graduate Student Council’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee; Graduate Women at MIT; the Undergraduate Association; the Black Students Union; and the Black Business Students Association.