The 2016 U.S. primary elections have been among the most eventful and contentious in recent memory. “Tumultuous,” “bizarre,” and “jaw-dropping” are just a few terms that have been used by members of the media to describe these elections. A number of analysts have predicted that one or both major political parties will face a contested national convention this summer.

With no method for selecting presidential candidates specifically elaborated in the U.S. Constitution, approaches have changed dramatically over time — even over the course of the past four decades. The School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (SHASS) Communications team recently spoke with Charles Stewart III, the Kenan Sahin Distinguished Professor of Political Science, and Devin Caughey, assistant professor of political science, about the history and development of the contemporary primary system, the prospect of contested conventions, and the nature of this year’s election cycle.

Stewart is a leader in the analysis of the performance of election systems and the quantitative assessment of election performance. In addition to his research on congressional politics, elections, and American political development, he serves as the co-director of the MIT/Caltech Voting Technology Project, a research effort that applies scientific analysis to questions about election technology, administration, and reform. Caughey’s research focuses on U.S. politics and political development. His current book project, "Representation without Parties: Reconsidering the One-Party South," examines the ideological evolution and diversity of Southern members of Congress and their relationship to public opinion in the region.

Q. When did the current U.S. presidential primary system develop?

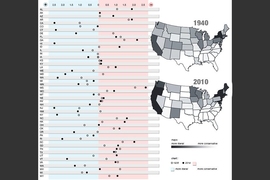

Stewart: It really developed in two parts. The innovation of primaries first started a century ago, as a part of the Progressive Era. The first primaries were in 1912, and very quickly over half of convention delegates for both major parties were chosen by primaries. They ebbed in popularity during the Depression, and didn’t make a comeback until 1972. Since then, roughly three-quarters of delegates to the two major party conventions have been chosen by primary.

Caughey: The shift back to presidential primaries was triggered by the 1968 election. In that year, Vice President Hubert Humphrey was the insider candidate for the Democratic nomination, but he faced insurgent challenges from anti-war candidates Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy. Humphrey, who decided to run only after President Lyndon Johnson withdrew, entered the race too late to compete in any primaries. He was nevertheless nominated at a turbulent national convention in Chicago.

In response to the controversy and taint of illegitimacy surrounding Humphrey’s nomination, the Democratic Party appointed a commission to consider changes to the process. The commission — initially chaired by Senator George McGovern — recommended that states be required to select delegates by more open procedures. State Democratic parties complied mostly by instituting presidential primaries, though some retained caucuses. Although the reforms did not apply to Republicans, in most states Republicans eventually emulated the Democrats so as not to appear less transparent or democratic than their rivals.

Q. What political considerations were in play in the design of the current presidential primary systems?

Stewart: The first major consideration was breaking the power of party bosses. Indeed, one could argue that this was true in both the 1910s and late 1960s — the two periods of the greatest expansion of the use of primaries. On the other hand, party leaders in the states regard primaries strategically. (Recall that the decision about whether a state has a primary, rather than caucuses, is made by leaders of each state’s parties.) Oftentimes they believe that their party’s nominee will fare better in the general election if they first competed in a primary earlier in the year.

On the other hand, as we have seen this year, those same leaders often want to exert control over the nomination process, and thus some have become disinclined to hold primaries. Finally — and this is an important point that’s frequently overlooked — some state parties have gone to primaries because the state pays for primaries and not caucuses; primaries are a way to shift costs off the state parties onto the state governments.

The Democrats have responded to another design consideration that the Republicans have mostly resisted. Democrats have “superdelegates,” a category created in response to the outsider candidacies of George McGovern (1972) and Jimmy Carter (1976 and 1980). The superdelegate concept springs from the recognition among Democrats that sometimes a candidate who can rally the base in a primary season may end up being a terrible general election candidate.

Caughey: The nomination process reforms were very destabilizing at first. They empowered ordinary voters, as well as the media, whose attention propelled the campaigns of several outsider candidates. In 1972, Senator McGovern capitalized on the system he helped create and rode a grass-roots campaign to the Democratic nomination — and then to a resounding defeat in November. In 1976, the lesser-known Jimmy Carter took a similar path to the Democratic nomination, as Ronald Reagan nearly pulled off a similar feat against the incumbent president, Gerald Ford.

By the 1980s, party insiders had developed formal and informal mechanisms of reasserting influence over the nomination process. Some of these changes were formal — such as the Democrat Party’s creation of superdelegates. But even more important were the informal ways that officials, donors, leading activists, and other party insiders learned to coordinate around their preferred candidate and signal their preferences to voters.

As Cohen, Karol, Noel, and Zaller argue in their influential 2008 book, "The Party Decides," voters largely followed these elite cues, restoring much of party insiders’ control over presidential nominations. Or at least that seemed to be the case before the last few elections, which have seen the return of insurgent candidates prevailing over insider candidates. This is particularly true in the current election.

Q. What are the strengths and limits of the current systems? Are there key differences between the two major parties?

Stewart: There are whole books to be written about the first question. Clearly, the greatest strength is that primaries allow candidates to build popular support, which is one of the most important functions of elections. Among the limits, I would start with two major ones. The first is the fact that at the end of the day, the selection process is still indirect.

Primary voters elect delegates who then go to a convention. The convention is antiquated, even if it’s not obvious what you would do instead. The second is the fact that there is not a good way to stage the progression of primaries. Why do some states get to go first all the time and not others? Is it fair that voters in the early states get a wider choice of candidates than later voters? Questions like these exist because of the vast size of the country and its federal structure.

Caughey: On the whole, the nomination procedures of the two major U.S. parties are more similar than they are different. The main advantage of the current nomination system is that it prevents party insiders from pushing through the nomination of someone who is clearly unpopular with its electoral coalition. But there are also downsides. One is that nomination procedures vary a lot across states, and those in some states can hardly be considered democratic.

Caucuses, in particular, require a large investment of time and effort that only a few citizens are able and willing to pay. Plus, Democratic Party caucuses don’t even have a secret ballot! While this may sometimes promote public deliberation and debate that is healthy for democracy, its main effect is to bias participation in caucuses towards the most politically committed and often ideologically extreme citizens.

Finally, there is also the problem that much of what drives citizen support for candidates is media exposure, and what drives media exposure is conflict, drama, and colorful or even outrageous personalities — not necessarily the best recipe for quality presidents.

Q. There has been discussion of possible contested conventions in this election cycle. What happens in a contested convention? Does it typically reinforce or conflict with voter preferences?

Caughey: What happens in a contested convention? Who knows?! We haven’t had one for many decades, and the last contested conventions occurred under a very different nomination system. One thing that I would say, however, is that the notion of a unified “voter preference” is generally illusory, but especially so in the context of a contested convention, which is likely to occur when there is no single candidate clearly preferred by the voters.

Stewart: The rules of both major party conventions require the nominee to get a majority of delegate votes in order to be nominated. If no one has a majority on the first ballot, the convention keeps on balloting until someone does. In the olden days, party bosses and leaders could deliver whole blocs of delegates to one candidate or the other, based on face-to-face bargains. Those days are gone. Thus, there is a question about how delegates would coordinate around a majority winner if there were to be a contested convention this time.

Judging whether a voting procedure reinforces or conflicts with voter preference is tricky business. If the delegates are sincere, representative supporters of the candidate they voted for on the first ballot, then subsequent ballots can be thought of as an exercise in which that candidates’ supporters figure out who their best choice is among the set of candidates who could get a majority.

The real question in 2016 is whether delegates are all, or even mostly, sincere supporters of the first-ballot candidate. There are reports, for instance, that many delegates who have been selected to vote for Donald Trump on the first ballot at the Republican convention would actually prefer Ted Cruz to get the nomination. If so, then it would be hard to argue that these delegates will go into second and subsequent ballots with the question in their minds, “What would be the best outcome for a Trump supporter?”

Q. If you could identify one reason for the tumult in this year’s set of presidential primaries, what would it be?

Caughey: If I had to identify one reason, it would be that party elites, especially on the Republican side, have lost a great deal of credibility with ordinary voters, who appear no longer to have sufficient trust in party elites to follow their choice of candidate. It does not help the party elites that the proliferation of media sources has made it harder for them to send a clear and dominant message that all partisans will receive.

Stewart: The leaders of both parties misjudged the degree to which their party’s core supporters distrust their leadership. That, of course, has played out differently in each party. For the Republicans, this distrust has become one of the key features of the front-runner’s appeal. For the Democrats, the distrust is more nuanced, and related to a frustration that a liberal president hasn’t achieved all his policy goals.

For both parties, I think this frustration arises out of a serious misunderstanding of how the American political process is designed to work. For that reason, I think the tumult will be here to stay so long as we have one party controlling the presidency and the other party controlling all, or part of, Congress.