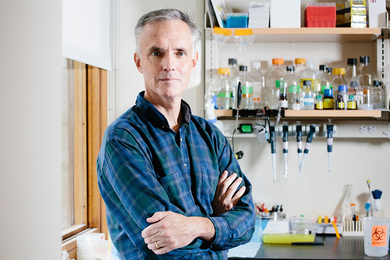

For years now, the chief strategy for curtailing North Korea’s ability to build more nuclear weapons has entailed attempts to block access to critical technologies needed by its nuclear program. But R. Scott Kemp, an assistant professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT and director of its recently formed Laboratory for Nuclear Security and Policy, has found evidence — by combing through publicly available sources— that the secretive state may have managed an end-run around those restrictions, enabling it to build centrifuges and other equipment needed to produce weapons-grade uranium. The findings were presented this week at a conference in South Korea by Kemp’s collaborator on the project, Joshua Pollack, a Washington-based security consultant. MIT News asked Kemp about how the new study was conducted and the significance of its findings.

Q. Can you describe the methodology you used to find out about these possible developments in North Korea’s nuclear capabilities?

A. One first needs a strong nuclear-engineering understanding of the technologies required to build a nuclear-weapons program from scratch. Equipped with this knowledge, it is then possible to perform a close analysis of open-source technical materials, such as journal articles, research reports and patents, to search for evidence of nuclear-weapon-enabling activities. An example would be modifications to a steel-making factory to produce a very particular grade of ultra-high-strength steel, or the development of control electronics for spinning centrifuges at speeds of 400 to 500 meters-per-second peripheral velocity. Individually, no one finding is significant, but a large number of time- and functionally correlated activities paints a picture of an emerging capability.

Searching for these bits of evidence is just as challenging as the technical interpretation of activities. The total volume of these materials is enormous, they are written in an archaic version of Korean used only in North Korea, and they are difficult to come by. Finding an effective filter is key. To reduce the burden of endless searching, we analyzed political materials such as propaganda, leadership travel schedules, and official commendations given to workers by the state. By observing where the North Korean government focuses its interests, we are able to narrow down on a handful of facilities and industrial activities from among many thousands, selecting associated technical reports for further analysis. We are now exploring the possibility of using Bayesian nonparametric classification and multimodal data fusion to automate this search process.

Q. How much certainty can one ascribe to these conclusions, and assuming they are correct, what are the implications in terms of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal?

A. We can only say that our findings suggest an increasing independence of the North Korean nuclear-weapons program in contrast to its earlier structure, which relied heavily on foreign technologies. In some cases we have established that North Korea is able to carry out a small subset of critical industrial activities at a scale significant enough to expand the nuclear program at a rapid rate, while other findings merely suggest achievements at the R&D level, but we lack evidence indicating whether these achievements have been industrialized.

However, our mission is not to draw firm conclusions about the precise state of affairs in North Korea. Rather, our goal is to understand how the country is organizing its strategic programs and how the United States might need to adjust its policies to improve the chances of reducing the North Korean nuclear-weapons threat. Historically, policymakers in the United States have presumed that North Korea was locked in the proverbial Stone Age, unable to organize indigenous research into advanced areas of engineering. U.S. intelligence was therefore largely predicated on counting the observed imports by North Korea, and our government’s efforts to slow the program were focused mostly on stopping the flow of tools and materials into North Korea rather than on diplomacy and engagement.

Our findings suggest a course correction may be necessary. Fewer imports means the intelligence agencies will be less able to gauge accurately the rate at which North Korea's program is expanding, and independence from foreign suppliers suggests that we may need to prepare ourselves to sit down and negotiate a peaceful and stable outcome to this 60-year-old standoff or risk facing a thoroughly nuclear-armed North Korea.

Q. What is the new Laboratory for Nuclear Security and Policy, and how does this research project fit in with the center’s plans and processes?

A. The mission of the Laboratory for Nuclear Security and Policy is to promote peace and stability in the use of nuclear energy by bringing advanced tools to bear on some of the most challenging nuclear-security problems. Much of what we do is focused on eliminating the risks posed by nuclear weapons, whether that be accidental or unauthorized use of existing weapons, the elimination of the extensive stocks of surplus nuclear weapons left over from Cold War arsenals, or preventing the spread of weapons to new countries. Our North Korea project is a typical example of how we use science to identify the boundary conditions of a policy problem, which we then translate into a family of solutions that take the form of policy recommendations. We also work to develop new technologies and tools to enable peace-promoting treaties by working to solve longstanding challenges associated with treaty verification. The most revolutionary results come when we are able to fuse cutting-edge technology by collaborating with scholars from across the many technical disciplines represented at MIT. This makes MIT a very exciting place to do this kind of research, and it’s nice to know that it helps make the world a better place too.

Q. Can you describe the methodology you used to find out about these possible developments in North Korea’s nuclear capabilities?

A. One first needs a strong nuclear-engineering understanding of the technologies required to build a nuclear-weapons program from scratch. Equipped with this knowledge, it is then possible to perform a close analysis of open-source technical materials, such as journal articles, research reports and patents, to search for evidence of nuclear-weapon-enabling activities. An example would be modifications to a steel-making factory to produce a very particular grade of ultra-high-strength steel, or the development of control electronics for spinning centrifuges at speeds of 400 to 500 meters-per-second peripheral velocity. Individually, no one finding is significant, but a large number of time- and functionally correlated activities paints a picture of an emerging capability.

Searching for these bits of evidence is just as challenging as the technical interpretation of activities. The total volume of these materials is enormous, they are written in an archaic version of Korean used only in North Korea, and they are difficult to come by. Finding an effective filter is key. To reduce the burden of endless searching, we analyzed political materials such as propaganda, leadership travel schedules, and official commendations given to workers by the state. By observing where the North Korean government focuses its interests, we are able to narrow down on a handful of facilities and industrial activities from among many thousands, selecting associated technical reports for further analysis. We are now exploring the possibility of using Bayesian nonparametric classification and multimodal data fusion to automate this search process.

Q. How much certainty can one ascribe to these conclusions, and assuming they are correct, what are the implications in terms of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal?

A. We can only say that our findings suggest an increasing independence of the North Korean nuclear-weapons program in contrast to its earlier structure, which relied heavily on foreign technologies. In some cases we have established that North Korea is able to carry out a small subset of critical industrial activities at a scale significant enough to expand the nuclear program at a rapid rate, while other findings merely suggest achievements at the R&D level, but we lack evidence indicating whether these achievements have been industrialized.

However, our mission is not to draw firm conclusions about the precise state of affairs in North Korea. Rather, our goal is to understand how the country is organizing its strategic programs and how the United States might need to adjust its policies to improve the chances of reducing the North Korean nuclear-weapons threat. Historically, policymakers in the United States have presumed that North Korea was locked in the proverbial Stone Age, unable to organize indigenous research into advanced areas of engineering. U.S. intelligence was therefore largely predicated on counting the observed imports by North Korea, and our government’s efforts to slow the program were focused mostly on stopping the flow of tools and materials into North Korea rather than on diplomacy and engagement.

Our findings suggest a course correction may be necessary. Fewer imports means the intelligence agencies will be less able to gauge accurately the rate at which North Korea's program is expanding, and independence from foreign suppliers suggests that we may need to prepare ourselves to sit down and negotiate a peaceful and stable outcome to this 60-year-old standoff or risk facing a thoroughly nuclear-armed North Korea.

Q. What is the new Laboratory for Nuclear Security and Policy, and how does this research project fit in with the center’s plans and processes?

A. The mission of the Laboratory for Nuclear Security and Policy is to promote peace and stability in the use of nuclear energy by bringing advanced tools to bear on some of the most challenging nuclear-security problems. Much of what we do is focused on eliminating the risks posed by nuclear weapons, whether that be accidental or unauthorized use of existing weapons, the elimination of the extensive stocks of surplus nuclear weapons left over from Cold War arsenals, or preventing the spread of weapons to new countries. Our North Korea project is a typical example of how we use science to identify the boundary conditions of a policy problem, which we then translate into a family of solutions that take the form of policy recommendations. We also work to develop new technologies and tools to enable peace-promoting treaties by working to solve longstanding challenges associated with treaty verification. The most revolutionary results come when we are able to fuse cutting-edge technology by collaborating with scholars from across the many technical disciplines represented at MIT. This makes MIT a very exciting place to do this kind of research, and it’s nice to know that it helps make the world a better place too.