In cities across America over the last two decades, high-rise public-housing projects, riddled with crime and poverty, have been torn down. In their places, developers have constructed lower-rise, mixed-use buildings. Crime has dropped, neighborhoods have gentrified, and many observers have lauded the overall approach.

But urban historian Lawrence J. Vale of MIT does not agree that the downsizing of public housing has been an obvious success.

“We’re faced with a situation of crisis in housing for those of the very lowest incomes,” says Vale, the Ford Professor of Urban Design and Planning at MIT. “Public housing has continued to fall far short of meeting the demand from low-income people.”

Take Chicago, where the last of the Cabrini-Green high-rises was torn down in 2011, ending a dismantling that commenced in 1993. Those buildings — just a short walk from the neighborhood where Vale grew up — have been replaced by lower-density residences. But where 3,600 apartments were once located, there are now just 400 units constructed for ex-Cabrini residents. Other Cabrini-Green occupants were given vouchers to help subsidize their housing costs, but their whereabouts have not been extensively tracked.

“There is a contradiction in saying to people, ‘You’re living in a terrible place, and we’re going to put massive investment into it to make it as safe and attractive as possible, but by the way, the vast majority of you are not going to be able to live here again once we do so,’” Vale says. “And there is relatively little effort to truly follow through on what the life trajectory is for those who go elsewhere and don’t have an opportunity to return to the redeveloped housing.”

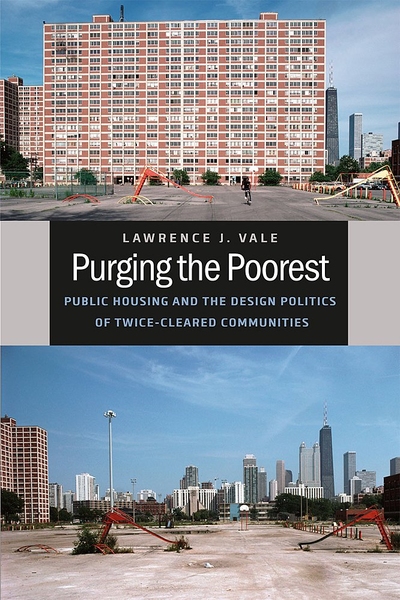

Now Vale is expanding on that argument in a new book, “Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities,” published this month by the University of Chicago Press. As Vale sees it, our focus on design in public housing — such as the problems inherent in high-rises — obscures the fact that design is a political issue, too: Building smaller structures, for instance, means we are deciding to take less responsibility for helping the poor.

Chicago and Atlanta, two ‘conspicuous experiments’

“Purging the Poorest” is a case study of two cities, Chicago and Atlanta. Both have essentially razed whole neighborhoods twice in the last 80 years: first transforming urban slums to public-housing projects starting in the 1930s, and then demolishing those buildings, since the 1990s, in favor of lower-density buildings.

“Chicago and Atlanta are probably the nation’s most conspicuous experiments in getting rid of, or at least transforming, family public housing,” Vale explains. However, he notes, “It’s hard to find an older American city that doesn’t have at least one example of this double clearance.”

Essentially, Vale says, these cities exemplify one basic question: “Should public resources go to the group most likely to take full advantage of them, or to the group that is most desperately in need of assistance?”

Vale sees U.S. policy as vacillating between these views over time. At first, public housing was meant “to reward an upwardly mobile working-class population” — making public housing a place for strivers. Slums were cleared and larger apartment buildings developed, including Atlanta’s Techwood Homes, the first such major project in the country.

But after 1960, public housing tended to be the domain of urban families mired in poverty. “The conventional wisdom was that public housing dangerously concentrated poor people in a poorly designed and poorly managed system of projects, and we are now thankfully tearing it all down,” Vale says. “But that was mostly a middle phase of concentrated poverty from 1960 to 1990.”

Over the last two decades, he says, the pendulum has swung back, leaving a smaller number of housing units available for the less-troubled, which Vale calls “another round of trying to find the deserving poor who are able to live in close proximity with now-desirable downtown areas.”

Vale’s critique of this downsizing involves several elements. Projects such as Cabrini-Green might have been bad, but displacing people from them means “the loss of the community networks they had, their church, the people doing day care for their children, the opportunities that neighborhood did provide, even in the context of violence.”

Demolishing public housing can hurt former residents financially, too. “Techwood and Cabrini-Green were very central to downtown and people have lost job opportunities,” Vale says. Indeed, the elimination of those developments, even with all their attendant problems, does not seem to have measurably helped many former residents gain work; the percentage of public-housing residents employed in Chicago has hovered around 50 percent even as the city has remade its housing.

Moreover, it is hard to track the status of most residents who have left the public-housing system — or to determine who should gain access to redeveloped public housing.

“We don’t have very fine-tuned instruments to understand the difference between the person who genuinely needs assistance and the person who is gaming the system,” Vale says. “Far larger numbers of people get demonized, marginalized or ignored, instead of assisted.”

Paved with good intentions

Despite the judgmental nature of the book’s title, Vale emphasizes that most policymakers and developers have launched the smaller-scale housing projects with good aims in mind.

“Many of the people who engaged in the displacement of people with low incomes did so with the best of intentions,” Vale says. “Private developers and housing authority officials genuinely believe they are acting in the best interests of low-income households.”

Other scholars praise the depth of Vale’s research and the historical sweep of his book. Bradford Hunt, an associate dean and professor of social science at Roosevelt University in Chicago, and an expert on his city’s public-housing policy, calls the book “an exceptional work of original scholarship” on “one of the most contentious urban policies to emerge from the New Deal.”

Ultimately, Vale thinks, the reality of the ongoing demand for public housing makes it an issue we have not solved.

“The irony of public housing is that people stigmatize it in every possible way, except the waiting lists continue to grow and it continues to be very much in demand,” Vale says. “If this is such a terrible [thing], why are so many hundreds of thousands of people trying to get into it? And why are we reducing the number of public-housing units?”

But urban historian Lawrence J. Vale of MIT does not agree that the downsizing of public housing has been an obvious success.

“We’re faced with a situation of crisis in housing for those of the very lowest incomes,” says Vale, the Ford Professor of Urban Design and Planning at MIT. “Public housing has continued to fall far short of meeting the demand from low-income people.”

Take Chicago, where the last of the Cabrini-Green high-rises was torn down in 2011, ending a dismantling that commenced in 1993. Those buildings — just a short walk from the neighborhood where Vale grew up — have been replaced by lower-density residences. But where 3,600 apartments were once located, there are now just 400 units constructed for ex-Cabrini residents. Other Cabrini-Green occupants were given vouchers to help subsidize their housing costs, but their whereabouts have not been extensively tracked.

“There is a contradiction in saying to people, ‘You’re living in a terrible place, and we’re going to put massive investment into it to make it as safe and attractive as possible, but by the way, the vast majority of you are not going to be able to live here again once we do so,’” Vale says. “And there is relatively little effort to truly follow through on what the life trajectory is for those who go elsewhere and don’t have an opportunity to return to the redeveloped housing.”

Now Vale is expanding on that argument in a new book, “Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities,” published this month by the University of Chicago Press. As Vale sees it, our focus on design in public housing — such as the problems inherent in high-rises — obscures the fact that design is a political issue, too: Building smaller structures, for instance, means we are deciding to take less responsibility for helping the poor.

Chicago and Atlanta, two ‘conspicuous experiments’

“Purging the Poorest” is a case study of two cities, Chicago and Atlanta. Both have essentially razed whole neighborhoods twice in the last 80 years: first transforming urban slums to public-housing projects starting in the 1930s, and then demolishing those buildings, since the 1990s, in favor of lower-density buildings.

“Chicago and Atlanta are probably the nation’s most conspicuous experiments in getting rid of, or at least transforming, family public housing,” Vale explains. However, he notes, “It’s hard to find an older American city that doesn’t have at least one example of this double clearance.”

Essentially, Vale says, these cities exemplify one basic question: “Should public resources go to the group most likely to take full advantage of them, or to the group that is most desperately in need of assistance?”

Vale sees U.S. policy as vacillating between these views over time. At first, public housing was meant “to reward an upwardly mobile working-class population” — making public housing a place for strivers. Slums were cleared and larger apartment buildings developed, including Atlanta’s Techwood Homes, the first such major project in the country.

But after 1960, public housing tended to be the domain of urban families mired in poverty. “The conventional wisdom was that public housing dangerously concentrated poor people in a poorly designed and poorly managed system of projects, and we are now thankfully tearing it all down,” Vale says. “But that was mostly a middle phase of concentrated poverty from 1960 to 1990.”

Over the last two decades, he says, the pendulum has swung back, leaving a smaller number of housing units available for the less-troubled, which Vale calls “another round of trying to find the deserving poor who are able to live in close proximity with now-desirable downtown areas.”

Vale’s critique of this downsizing involves several elements. Projects such as Cabrini-Green might have been bad, but displacing people from them means “the loss of the community networks they had, their church, the people doing day care for their children, the opportunities that neighborhood did provide, even in the context of violence.”

Demolishing public housing can hurt former residents financially, too. “Techwood and Cabrini-Green were very central to downtown and people have lost job opportunities,” Vale says. Indeed, the elimination of those developments, even with all their attendant problems, does not seem to have measurably helped many former residents gain work; the percentage of public-housing residents employed in Chicago has hovered around 50 percent even as the city has remade its housing.

Moreover, it is hard to track the status of most residents who have left the public-housing system — or to determine who should gain access to redeveloped public housing.

“We don’t have very fine-tuned instruments to understand the difference between the person who genuinely needs assistance and the person who is gaming the system,” Vale says. “Far larger numbers of people get demonized, marginalized or ignored, instead of assisted.”

Paved with good intentions

Despite the judgmental nature of the book’s title, Vale emphasizes that most policymakers and developers have launched the smaller-scale housing projects with good aims in mind.

“Many of the people who engaged in the displacement of people with low incomes did so with the best of intentions,” Vale says. “Private developers and housing authority officials genuinely believe they are acting in the best interests of low-income households.”

Other scholars praise the depth of Vale’s research and the historical sweep of his book. Bradford Hunt, an associate dean and professor of social science at Roosevelt University in Chicago, and an expert on his city’s public-housing policy, calls the book “an exceptional work of original scholarship” on “one of the most contentious urban policies to emerge from the New Deal.”

Ultimately, Vale thinks, the reality of the ongoing demand for public housing makes it an issue we have not solved.

“The irony of public housing is that people stigmatize it in every possible way, except the waiting lists continue to grow and it continues to be very much in demand,” Vale says. “If this is such a terrible [thing], why are so many hundreds of thousands of people trying to get into it? And why are we reducing the number of public-housing units?”