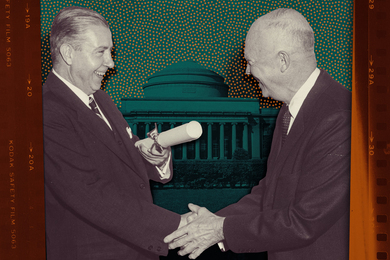

Leonard S. Lerman, a former senior lecturer at MIT and a molecular biologist whose groundbreaking research shaped the way we analyze and manipulate DNA, died Sept. 19 in Cambridge after a long illness.

In the early 1960s, Lerman proposed that certain chemicals insert into DNA by intercalation, requiring the DNA double helix to unwind so that the base pairs separate to a certain extent, the degree of separation depending on the intercalator. The unwinding can induce local structural changes in the DNA, which may have serious functional consequences, including the generation of mutations. DNA intercalators, such as aflatoxins and acridines, are often carcinogenic, but can also be potent anticancer agents.

On sabbatical leave from the Medical Research Council Laboratories in Cambridge, England, and working with Sydney Brenner and Francis Crick, Lerman generated mutations with DNA-intercalating chemicals; the results were fundamental to the “triplet code” hypothesis for protein synthesis — the way DNA sequences are “read” to specify protein sequences.

Lerman also pioneered the use of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis to detect and localize single base changes in genomic DNA and to separate DNA fragments based on their sequence composition. These approaches have had important applications in the screening for variants in human genes, in diagnosing mutations associated with genetic diseases, and in discerning biodiversity in microbial communities.

A member of the National Academy of Sciences, Lerman served on the faculties of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, and the State University of New York at Albany. He later worked at the Genetics Institute in Boston and was a senior lecturer at MIT.

An inspired gadgeteer, he was known for his creative solutions to everyday problems. He conceived of and built a TV remote control before these were commercially available and, after a visitor accidentally soaked a plaster cast in the guest room shower, he contrived a connection to a vacuum cleaner that dried the cast in a few minutes.

Leonard Solomon Lerman was born in 1925 in Pittsburgh, of Ukrainian-Jewish parents. At Taylor Allderdice High School, he studied under Lon Colborn, a legendary chemistry teacher who launched more than 300 students into careers in science. At age 16, Lerman won a science radio show contest in Pittsburgh, and was awarded a scholarship to attend Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). Entering college before he had received a high school diploma, Lerman completed his undergraduate education in five semesters, subsequently working in an experimental weapons research lab during World War II. He did graduate work under Linus Pauling at the California Institute of Technology and completed a PhD in chemistry in 1950.

Lerman mentored two graduate students who went on to win major scientific awards: Sidney Altman (1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) and Tom Maniatis (2012 Lasker-Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science). He is survived by his partner of 20 years, Lisa Steiner, of Cambridge; his former wife, Elizabeth Taylor; three children from his first marriage, to the late Claire Lindegren Lerman, daughters Averil and Lisa and son Alexander; and seven grandchildren.

In the early 1960s, Lerman proposed that certain chemicals insert into DNA by intercalation, requiring the DNA double helix to unwind so that the base pairs separate to a certain extent, the degree of separation depending on the intercalator. The unwinding can induce local structural changes in the DNA, which may have serious functional consequences, including the generation of mutations. DNA intercalators, such as aflatoxins and acridines, are often carcinogenic, but can also be potent anticancer agents.

On sabbatical leave from the Medical Research Council Laboratories in Cambridge, England, and working with Sydney Brenner and Francis Crick, Lerman generated mutations with DNA-intercalating chemicals; the results were fundamental to the “triplet code” hypothesis for protein synthesis — the way DNA sequences are “read” to specify protein sequences.

Lerman also pioneered the use of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis to detect and localize single base changes in genomic DNA and to separate DNA fragments based on their sequence composition. These approaches have had important applications in the screening for variants in human genes, in diagnosing mutations associated with genetic diseases, and in discerning biodiversity in microbial communities.

A member of the National Academy of Sciences, Lerman served on the faculties of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, and the State University of New York at Albany. He later worked at the Genetics Institute in Boston and was a senior lecturer at MIT.

An inspired gadgeteer, he was known for his creative solutions to everyday problems. He conceived of and built a TV remote control before these were commercially available and, after a visitor accidentally soaked a plaster cast in the guest room shower, he contrived a connection to a vacuum cleaner that dried the cast in a few minutes.

Leonard Solomon Lerman was born in 1925 in Pittsburgh, of Ukrainian-Jewish parents. At Taylor Allderdice High School, he studied under Lon Colborn, a legendary chemistry teacher who launched more than 300 students into careers in science. At age 16, Lerman won a science radio show contest in Pittsburgh, and was awarded a scholarship to attend Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). Entering college before he had received a high school diploma, Lerman completed his undergraduate education in five semesters, subsequently working in an experimental weapons research lab during World War II. He did graduate work under Linus Pauling at the California Institute of Technology and completed a PhD in chemistry in 1950.

Lerman mentored two graduate students who went on to win major scientific awards: Sidney Altman (1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) and Tom Maniatis (2012 Lasker-Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science). He is survived by his partner of 20 years, Lisa Steiner, of Cambridge; his former wife, Elizabeth Taylor; three children from his first marriage, to the late Claire Lindegren Lerman, daughters Averil and Lisa and son Alexander; and seven grandchildren.