Joseph G. Gavin Jr., former president of Grumman Corp. who led the company’s development of the Lunar Module for the Apollo program, died this week in Amherst, Mass. at the age of 90. Gavin was a life member of the MIT Corporation.

Gavin, who earned SB and SM degrees in aeronautical engineering from MIT in 1941 and 1942, served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, where he worked on early jet-powered fighter aircraft. He then joined Grumman, where he worked for 39 years. For 10 years, he was Grumman’s Director of the Lunar Module Program for Apollo, and in 1972 became the company’s president. He retired from Grumman in 1985, and since then lived in Amherst, Mass.

In an interview last year with Technology Review, Gavin recalled his experiences with the Apollo program, saying “There’s a certain exuberance that comes from being out on the edge of technology, where things are not certain, where there is some risk, and where you make something work.”

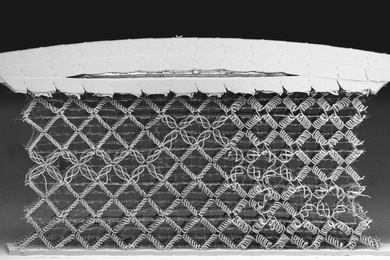

That risk became very real in April 1970 when the Apollo 13 mission was rocked by an explosion that severely damaged the spacecraft. NASA and Grumman engineers scrambled to improvise an emergency procedure to save the crew by using the Lunar Module, which Grumman had developed, as a kind of lifeboat. “That was the tensest episode in my career,” Gavin said. “The team at Grumman developed a personal relationship with every one of the astronauts in the Apollo era. We were building machines that our friends would operate — not some faceless individuals unknown to us.”

Richard Battin, a senior lecturer in MIT’s Aeronautics and Astronautics department who worked extensively with Gavin on the Apollo lander project, whose guidance and navigation system Battin directed in what was then the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, says that Gavin remained passionately interested in education and appeared regularly in a freshman seminar that Battin taught. “He was really good with the freshmen,” Battin says. “I didn’t even have to ask” him to participate in the seminar, he says. “He would call me up” to ask to take part.

Carl Mueller, a fellow member of MIT’s class of ’41, in remarks delivered in 1995 when Gavin was made a life member emeritus of the MIT Corporation, said that “his generosity and abiding concern have strengthened this institution immeasurably,” and called him “a modest, gentle man whose powerful intellect and effective leadership have literally put men on the moon and returned them safely to Earth.”

Gavin received the NASA Distinguished Public Medal In 1971 and was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1974. He was also a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

“There are probably people who would say I was a workaholic,” he said in the Technology Review interview. “But when I was at Grumman I was doing something I would have preferred to do over anything else. When you’re in that situation, the hours don’t mean much. You do whatever is necessary.”

He is survived by his wife of 67 years, Dorothy, his sons, Joseph III and Donald, and four grandchildren. A daughter, Tay Anne Gavin Erickscon, died in 1998.

Gavin, who earned SB and SM degrees in aeronautical engineering from MIT in 1941 and 1942, served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, where he worked on early jet-powered fighter aircraft. He then joined Grumman, where he worked for 39 years. For 10 years, he was Grumman’s Director of the Lunar Module Program for Apollo, and in 1972 became the company’s president. He retired from Grumman in 1985, and since then lived in Amherst, Mass.

In an interview last year with Technology Review, Gavin recalled his experiences with the Apollo program, saying “There’s a certain exuberance that comes from being out on the edge of technology, where things are not certain, where there is some risk, and where you make something work.”

That risk became very real in April 1970 when the Apollo 13 mission was rocked by an explosion that severely damaged the spacecraft. NASA and Grumman engineers scrambled to improvise an emergency procedure to save the crew by using the Lunar Module, which Grumman had developed, as a kind of lifeboat. “That was the tensest episode in my career,” Gavin said. “The team at Grumman developed a personal relationship with every one of the astronauts in the Apollo era. We were building machines that our friends would operate — not some faceless individuals unknown to us.”

Richard Battin, a senior lecturer in MIT’s Aeronautics and Astronautics department who worked extensively with Gavin on the Apollo lander project, whose guidance and navigation system Battin directed in what was then the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, says that Gavin remained passionately interested in education and appeared regularly in a freshman seminar that Battin taught. “He was really good with the freshmen,” Battin says. “I didn’t even have to ask” him to participate in the seminar, he says. “He would call me up” to ask to take part.

Carl Mueller, a fellow member of MIT’s class of ’41, in remarks delivered in 1995 when Gavin was made a life member emeritus of the MIT Corporation, said that “his generosity and abiding concern have strengthened this institution immeasurably,” and called him “a modest, gentle man whose powerful intellect and effective leadership have literally put men on the moon and returned them safely to Earth.”

Gavin received the NASA Distinguished Public Medal In 1971 and was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1974. He was also a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

“There are probably people who would say I was a workaholic,” he said in the Technology Review interview. “But when I was at Grumman I was doing something I would have preferred to do over anything else. When you’re in that situation, the hours don’t mean much. You do whatever is necessary.”

He is survived by his wife of 67 years, Dorothy, his sons, Joseph III and Donald, and four grandchildren. A daughter, Tay Anne Gavin Erickscon, died in 1998.