Stroll down the sixth-floor hallway of the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research in Building 37 and you'll see images of the Milky Way in molecular clouds, the Folded-port InfraRed Echellette spectrometer and simulations of cold dark matter caustics.

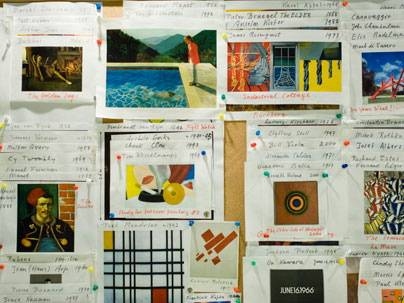

Walk a little farther, and you'll see a Rembrandt, a Hockney, a Picasso and many more reproductions by famous artists ranging from Giotto to Judd. This unexpected burst of art in an enclave of science and technology is the brainstorm of MIT physics professor and art lover Walter Lewin.

For six years, Lewin has used the board as a platform to run a weekly art quiz to pique curiosity and invite involvement by colleagues and students. Every Sunday, he posts a printout of an artwork; participants then use a little cardboard ballot box to submit their best guess as to who the artist is. The following weekend, Lewin posts the answer and starts the process all over again. At the end of each year, he awards art books to the three participants who got the most answers right.

A few years ago, Elizabeth Kubicki, an assistant in the Microsystems Technology Laboratories, was walking down the hall when the riotous gallery of thumbtacked images caught her eye.

Intrigued, she started playing the quiz, becoming a detective of sorts in the process. How could one figure out the creator of an unknown piece? First, she estimates the piece's time period, then turns to her art books and the web to determine the most important artists from that era. "I examine the art piece for specific elements significant to a particular artist -- brush stroke, color, manner and favorite shapes," she said.

Her participation in the quiz has not only resulted in several sumptuous art books as prizes from Lewin, but she also says she has learned profound lessons about the creative process.

"Art is a never-ending progress of inner expression," she says. "It's an inevitable journey from superior cave paintings at Lascaux from 32,000 years ago to the new dialectic of Mark Rothko's Orange and Yellow, 1956."

Lewin developed his passion for art as a child in his native Holland through his parents' art collection and visits to the Gemeente Museum in The Hague. While at MIT years later, he met renowned Dutch computer artist Peter Struycken.

"My parents had several of his works in their collection," Lewin said. "Peter and I became close friends. He made me 'see' art; before I knew him, I only 'looked' at art. I learned how to appreciate and evaluate the pioneering contributions in art."

Lewin collaborated with Struycken on the latter's art during the late 1970s; the physicist's increasing expertise in art history led to an invitation from the Beuymans Museum in Rotterdam to give the first Mondrian Lecture to a crowd of 900 in Amsterdam in 1979. He has even started an art collection of his own, now totaling about 125 pieces.

"Art is still pivotal in my life," says Lewin. "I can't even imagine what my life would be without it. An appreciation for art and, above all, knowledge of art enriches your life and broadens your horizons."

Kubicki agrees. "Art is mirroring our life, art is exercising our freedom and art is implementing our intellect."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on December 17, 2008 (download PDF).