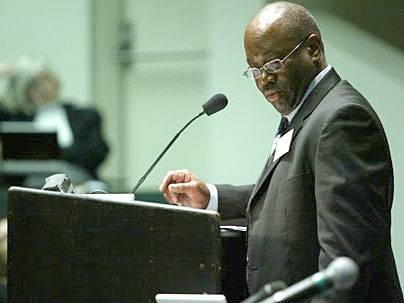

Wes Henderson got his first career counseling in elementary school, he told the audience at the Saturday, March 17 session of the two-day conference, "Architecture Race Academe: The Black Architect's Journey."

In the first-grade classroom of the segregated elementary school he attended, his teacher noticed the houses he was drawing and told him, "Oh, you should be an architect!"

"I hadn't really put a name to what I was doing, but she did that for me," Henderson said last weekend of that first-grade teacher.

He remembered the advice and ultimately heeded it.

He went on to earn two architecture degrees from MIT, in 1974 and 1976, and later a doctorate from UCLA.

After spending many years at universities in his home state of Texas, he now teaches architecture at Florida A&M University.

Henderson noted that the exchange with his first-grade teacher was but one example at the conference of how a specific bit of well-timed advice made a difference in the life of someone who would go on to become an architect.

The numbers in the room were small-just a few dozen on the gray, rainy Saturday morning after Friday's big snowstorm.

But then the numbers of blacks in architecture are small. In some categories-black professors who are full-time faculty at a top-tier institution-they can be counted literally on the fingers of one hand, according to numbers presented by Lawrence Sass, MIT assistant professor of architecture.

And because the numbers are so small, the discussions made clear, each black architect makes an individual journey. Many of the architects chose their path in response to specific pieces of advice they got from trusted mentors-counsel that probably took moments to impart but has been remembered ever since.

Sass, for instance, said that he had been advised to take the time to develop a personal portfolio of work-not always a top priority for debt-laden new graduates. "I get the feeling that most people … don't know how desperately important that is," as a preparation for academic appointments.

Some implicit recommendations for universities seeking to welcome more black architects-in-training:

- Make better use of black alumni as recruiters; follow up with alumni who have written letters of recommendation. This isn't always done, Henderson said.

- Pay attention to the visuals on campus: Even something as simple as display-case photos of racially mixed intramural sports teams can telegraph a message of inclusion.

- Ensure that black students have not only appropriate academic preparation but familiarity with the way things are done at a particular university.

Henderson credited Dolores Hayden, formerly of MIT and now of Yale, for facilitating his admission to UCLA. "She helped me see I needed to do more writing, go to more conferences."

He also credited Stanford Anderson, professor of architecture at MIT, as a mentor who wouldn't perhaps define himself as a mentor but who "maybe inadvertently" gave him some opportunities, including a field trip to Paris. "Did he take me?" Henderson asked rhetorically. "No, he took the whole class." But Henderson benefited along with everyone else. Mentors like these "let me see what an academic does," he said.

Not everyone, though, was convinced that structured mentoring is the best way to get more blacks into architecture. "It's not about who can take you by the hand and lead you through the system," as one participant put it. "It's about getting more people interested in architecture as a profession."

Janet E. Helms, Augustus Long Professor of counseling psychology and director the The Institute for the Study and Promotion of Race and Culture at Boston College, gave the morning's keynote address. Panels focused on teaching and practicing architecture; panelists included MIT alumnus Robert T. Coles.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on March 21, 2007 (download PDF).