Scientists, ethicists and members of diverse religions debated the difficult questions raised by advances in neuroscience at an MIT conference held April 17-19.

The conference, "Our Brains and Us: Neuroethics, Responsibility and the Self," drew 40 speakers and 130 attendees to a broad range of sessions that defined the evolving field of neuroethics, examined the concept of the self, debated moral agency and free will, discussed legal and religious ramifications and revealed technological advances such as brain-computer interfaces. The conference was organized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the MIT Brain and Cognitive Sciences Department, the MIT Technology and Culture Forum and the Boston Theological Institute.

"Our primary goal was to promote a dialogue among people who were neuroscientists and those who were not, but who wanted to look at what ethical issues neuroscience raises," said Stephanie Bird, former special assistant to the provost and vice president for research at MIT. Bird spoke on a panel titled "Neuroscience and Neuroethics."

"The field has evolved to a point where there is an enormous amount of hype about the extent to which new methods in neurosciences enable high levels of control of people," said Stephan Chorover, professor of psychology in the MIT Brain and Cognitive Sciences Department. But the complexity of humans and the brain will make it difficult for advances in neuroscience to accurately control or predict human action, he said.

Another concern about scientific study of the brain is that biology will strip life of its meaning, said Steven Pinker, professor of psychology at Harvard University and a former professor at MIT. "The fear of nihilism is commonly perceived as a major moral risk of neuroscience," he said.

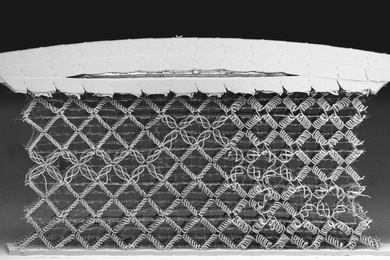

Paul Root Wolpe, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and a bioethics fellow, said that any therapy that can alter the brain or behavior will be based on cultural, religious and moral judgments that are dictated by society. He added that society also defines what is normal. "Integrating technology into humans may be OK," he said, such as brain-computer interfaces that can allow a paralyzed person to communicate and an experimental prosthetic device that one day might be used to replace damaged brain tissue.

There is some debate about what the field of neuroethics should encompass. Bird said it is an area of biomedical ethics that focuses on issues unique to neuroscience. "It is an area that is complex and dramatic like the nervous system, but we want to find ways to approach it," she said, pointing to difficult questions that arise when applying findings in neuroscience and considering whether they will be used to control or modify public behavior.

Said Wolpe, "We need to look at what we mean by normality at a time when we'll be able to manipulate our bodies and brains as never before."

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on April 27, 2005 (download PDF).