CAMBRIDGE, Mass.--An MIT researcher explains in the August issue of Nature Neuroscience how temporarily depriving one eye of vision soon after birth induces a long-lasting loss of synapses that causes blindness.

The same brain mechanisms are used for normal development and may go awry in conditions that cause developmental delays in humans, and may reappear in old age and contribute to synaptic loss during Alzheimer's disease.

The brain's ability to adapt to environmental changes is called plasticity. During infancy and early childhood, synaptic connections are sculpted by sensory experience. One mechanism for this plasticity is called long-term potentiation (LTP), in which brain cells improve their ability to communicate with one another. Its counterpart is long-term depression (LTD), in which neurons have less ability to send information over synapses. These two mechanisms normally work together to fine-tune connections. However, the mechanisms of LTD left unchecked could have harmful consequences, possibly including fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited form of mental retardation.

Understanding LTD helps solve the 40-year-old mystery of why temporarily covering one of an animal's eyes shortly after birth caused permanent blindness in that eye.

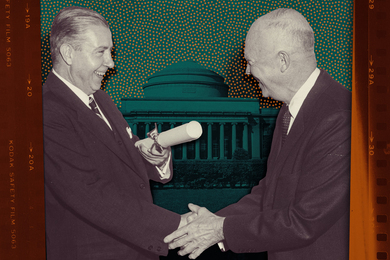

MIT's Mark F. Bear and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University Medical School report that depriving one eye of sight in newborn rats for 24 hours induces LTD in the visual cortex. Bear is a professor of brain and cognitive sciences in the Picower Center for Learning and Memory at MIT and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

It turns out the induced blindness is not due to "use it or lose it." Bear, who studies how early experience modifies synapses in the brain, says the weakening and elimination of synapses serving the deprived eye occurs because activity in the closed eye no longer correlates with responses from the other eye.

Bear helped establish the experimental model of LTD. Previous research had shown that LTD--which normally occurs only during a critical period of early development and not at all in adulthood--can be induced in various ways, but it was not understood how these mechanisms contribute to experience-dependent, long-term synaptic changes.

Through a series of experiments, Bear and Arnold J. Heynen, research scientist at the Picower Center; Bong-June Yoon, research affiliate at the Picower Center; MIT graduate student Cheng-Hang Liu; and Hee J. Chung and Richard L. Huganir of Johns Hopkins reconstructed for the first time the molecular chain of events that is set in motion by depriving one eye of vision in young mammals.

"It is now understood that LTD is a consequence of the modification and removal of postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors, which likely precedes the physical elimination of the synapse," Bear said. "Our new paper brings the story full circle by showing that monocular deprivation produces exactly this same change in the visual cortex: the modification and loss of glutamate receptors. LTD contributes to the sculpting of connections during development."

In other words, glutamate acts as a messenger that lets neurons communicate. For a neuron to receive a message, it must have a glutamate receptor. In LTD, those receptors are modified and removed, leading synapses to disappear.

This work is funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Eye Institute.