MIT scientists have found a pulsar in a binary star system that has all but completely whittled away its companion star, leaving this companion only about 10 times more massive than Jupiter. The system has one of the lowest-mass companions of any stellar binary.

The finding provides clear evidence that neutron stars can slowly "accrete" (i.e., steal) material from their companions and dramatically increase their spin rate, ultimately evolving into the isolated, radio wave-emitting pulsars spinning a thousand times per second--the type commonly seen scattered throughout the Milky Way galaxy.

The maligned companion, once a bright orange gem probably more than half the mass of our sun (equivalent to 500 times the mass of Jupiter), has slowly grown dimmer and dimmer and will eventually vanish without even a whimper.

Dr. Ron Remillard of the Center for Space Research discovered the pulsar along with Drs. Jean Swank and Tod Strohmayer of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. The X-ray source, named XTE J0929-314, was found in mid-May during a routine survey of the sky with NASA's Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer.

Duncan Galloway, an MIT postdoctoral associate, performed the follow-up observation that revealed the pulsar system's unique properties. Other members of the MIT observation and analysis team include Dr. Edward Morgan and Professor Deepto Chakrabarty.

"This pulsar has been accumulating gas donated from its companion for quite some time now," said Galloway. "It's exciting that we're finally discovering pulsars at all stages of their evolution, that is, some that are quite young and others that are transitioning to a final stage of isolation."

A pulsar is a neutron star that emits steady pulses of radiation with each rotation. A neutron star is the skeletal remains of a massive star that exhausted its nuclear fuel and subsequently ejected its outer shell in a supernova explosion. The remaining core, still possessing about a sun's worth of mass, collapses to a sphere no larger than Cambridge, about 12 miles in diameter.

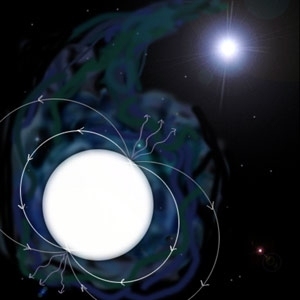

Neutron stars in "low mass" binary star systems such as the one observed here (where the companion has less mass than the sun) have been suspected as the sites where slowly spinning neutron stars are spun up to millisecond spin periods. A neutron star has a powerful gravitational field, and it can accrete gas from its companion. Matter spirals toward the neutron star in the form of an accretion disk, a journey visible in X-ray radiation. In doing so, it transfers its orbital energy to the neutron star, making it spin faster and faster--in this case, 185 times per second.

In the XTE J0929-314 system--only the third known "accreting" millisecond pulsar of its kind and the second identified with the Rossi Explorer in the past two months--the pulsar orbits its companion every 43 minutes. In fact, the entire binary system would fit within the orbit of the moon around the Earth, which takes a month, making this one of the smallest binary orbits known.

While the first two accreting, millisecond pulsars discovered lie near the direction of the galactic center, the latest discovery lies in a completely different direction. "One advantage of XTE J0929-314 is that observations are less affected by crowded star fields and interstellar gas and dust," Morgan noted.

"This binary system is a rare find," said Chakrabarty, who works extensively on neutron stars in the galaxy. "It will help us understand the link between slow-spinning pulsars in binary systems, which are quite common, and fast-spinning isolated pulsars, which are commonly seen by radio astronomers."

With XTE J0929-314 and its 10-Jupiter-mass companion, MIT scientists have stumbled on a pulsar that may be further along its path to becoming isolated. The companion will eventually vanish as a result of both the force of gravity pulling matter onto the neutron star (accretion), and the pressure from the resulting X-ray radiation emitted from the neutron star blowing matter away from the companion (ablation).

Also, this is one of the faintest transients yet discovered with the Rossi Explorer's All-Sky Monitor. "It was found by superimposing on the sky the thousands of snapshots that our three panning cameras provide in a given week of observations," said Remillard. "The results demonstrate the value of this analysis exercise and the fact that important science is not confined to the sources with the brightest or most dramatic outbursts."

The Rossi Explorer's All-Sky Monitor is an instrument designed and constructed at MIT. Follow-up observations were made with the Rossi Explorer's Proportional Counter Array instrument, which was built by a team at NASA Goddard.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on June 5, 2002.