CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers will report in the June 21 issue of Nature that they have pinpointed how and where abstract thoughts are represented in the brain.

The study, in which monkeys apply rules about "same" and "different" to a myriad of images, shows that the prefrontal cortex -- the part of the brain directly behind the eyes -- works on the abstract assignment rather than simply recalling the pictures.

In other words, the MIT researchers have identified the part of the brain that figures out the rules of the game, but does not play the game. Most previous brain research has uncovered brain regions that perform concrete tasks, such as recognizing places or moving muscles.

These results could change the way psychiatrists and others think about the effects of damage from illness or injury to the prefrontal cortex, said author Earl K. Miller, "Class of 1956" Associate Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences in MIT's Center for Learning and Memory (CLM).

Widely thought to be a memory problem, these patients' inability to coordinate their lives may be more of an abstract thinking problem. "This makes sense, because complex behaviors all rely on knowing the 'rules of the game,'" Miller said.

Abnormal functioning of the prefrontal cortex is implicated in schizophrenia, attention deficit disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and other diseases. Miller's laboratory is one of a handful in the world developing and testing hypotheses on how the prefrontal cortex does its job.

TEACHING MONKEYS NEW TRICKS

Miller and lead author Jonathan D. Wallis, postdoctoral fellow in CLM, are interested in is the deepest issue in cognitive science, called executive or cognitive control. "It governs how you decide what behaviors to engage in, how you make decisions, how you decide what to pay attention to, what to do with your life," Miller said.

"We do not know how, or even whether, prefrontal cortex neurons can encode abstract rules," the authors write. "Virtually nothing is known about how these abstractions are stored in the brain."

You can't teach a monkey an abstract concept such as world peace, but you can teach it -- with much patience and effort -- to apply a general rule to different situations.

The researchers trained monkeys to identify whether hundreds of different pictures were the same or different. By recording signals from brain cells, or neurons, in the prefrontal cortex of monkeys as they perform cognitive tasks, scientists explore which circuits hold information "in mind," a skill necessary for information processing and thinking.

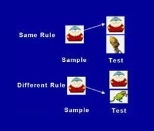

The monkeys were sometimes required to release a joystick if a picture was the same as the one shown before it and sometimes if the pictures were different. The monkeys could apply the rule to pictures they had never seen before, showing that they were really dealing with abstractions, Wallis said.

After more than nine months of training, the monkeys were able to respond instantly to the rule and were right more than 85 percent of the time. Still, judging by the difficulty of the training, Wallis said this task is about at the limit of the animal's intelligence.

Before each test, the monkey was given cues (a sip of juice or a tone) to indicate whether it was being asked to find a match or non-match. The monkey then looked at the pictures and responded with the joystick.

In each test, the animals had to apply the abstract rule of same or different and recall the individual photos. "By far the majority of the neurons were concerned with the abstract concept than with short-term memory," Wallis said. "Much to our surprise, a huge number of neurons had the rules of the game as their primary concern."

A NEW TAKE ON BRAIN DYSFUNCTION

In studies of monkeys and humans with damage to the prefrontal cortex, researchers have found many of the same cognitive problems seen in schizophrenic patients. Among them is what is widely believed to be a disorder of working memory, which allows you to keep several pieces of information in mind simultaneously.

The current work provides another explanation for loose associations, inattentiveness and disordered thought processes found in schizophrenics.

People with impaired prefrontal cortex function often cannot manage the day-to-day responsibilities of work or relationships. While it is necessary to hold items in short-term memory to carry out these tasks, "you also have to exhibit general principles of behavior to keep on task," Miller said. Otherwise, you are totally stimulus-bound -- if you see something, you act on it automatically whether or not it helps you achieve your goal.

The authors of the study reported in Nature are Miller, Wallis and MIT postdoctoral associate Kathleen C. Anderson, also affiliated with CLM.

The Center for Learning and Memory at MIT was established in May 1994 as an independent research center between the departments of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Biology. The mission of this multidisciplinary center is to decipher the brain's molecular and cellular mechanisms and the neural circuitry underlying learning and memory and to piece the puzzle together into an understanding of the intelligent and complex functioning of the brain.

This work is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of Mental Health, the RIKEN-MIT Neuroscience Research Center and the Class of 1956 chair.