"At two sharp (we) appeared in running clothes in the Stadium itself, just as the Games were about to commence," wrote Thomas Pelham Curtis, class of 1894 and winner of the 110-meter hurdles competition in the first modern Olympics a century ago. "The sight that met our eyes was one never to be forgotten. Row after row of people all dressed in holiday attire lined the seats of the Stadium, while at the end sat the King and Royal Family of Greece, the King of Serbia, two Grand Dukes of Russia, and hundreds of officers of different nationalities, all in the gayest of uniforms. 82,000 people were seated and 30,000 more, for whom there was no room, were standing tier on tier on a hill that towered above one side of the seats."

Mr. Curtis traveled to Greece with a last-minute American team from the Boston area and came away with first place in a race he reported as "nip and tuck from start to finish." The games were a

revival of the ancient games that had been last run in 393 AD and ended by the emperor Theodosius. Mr. Curtis recorded the 1896 games in a 1924 issue of Technology Review.

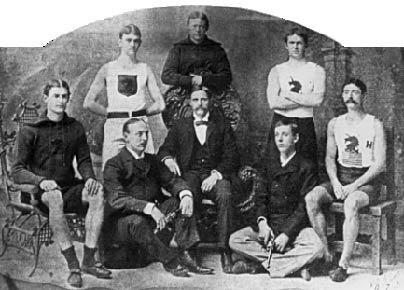

Mr. Curtis, who came to MIT from St. Paul, MN to study electrical engineering, was very active in his MIT class-playing and serving as vice president on the varsity football team, acting as chief marshal of

the Class Day committee and competing with the track team. He did not officially graduate with the class, though. In the 1893-94 yearbook, "The Technology Portfolio," he was listed as one of 28 students who were "intimately connected with the class of 1894 who did not try for degrees."

"Only six men had been left from the trial heats, including a Frenchman, an Englishman, a Greek and two Germans," Mr. Curtis wrote. "The race was nip and tuck from start to finish, both the Englishman and myself clearing the tenth hurdle abreast. I beat him out in the stretch by a scant two feet." He ran the hurdles that day in 17.6 seconds. Mr. Curtis commented that the Olympic records from those first modern games were not particularly good because of the stadium's soft and uncompleted track, "but there was a romance and a novelty connected with them that is hard to describe."

On-board training

The American athletes also were not completely prepared beforehand. Curtis' party-members of the Boston Athletic Club-decided to compete in the Olympics at the last minute, joining a team from Princeton, and set sail for Greece less than two weeks before the opening event. To prepare the athletes for the competition, the steamship Fulda's rear deck was cleared from 3-4pm each day and used for practicing the various events. The team took advantage of the ship's stop in Gibraltar for more practice. "While the other passengers hired carriages, guides, etc., and spent their time in sight-seeing, we took our spiked shoes and other paraphernalia, and visited the racing park belonging to the English officers stationed there," according to Curtis.

The Boston team arrived in Athens on Sunday, April 5, the day before the games began. They were greeted enthusiastically and were marched through town to a City Hall banquet where "great surprise was shown at our hesitation in drinking great bumpers of white wine which were forced upon us."

On the first day of competition, Mr. Curtis and his teammate T.E. Burke were entered in heats for the 100-meter race (the program's first), which had 24 competitors from all over Europe. Both won their

heats by narrow margins. Mr. Curtis also ran the preliminaries of the 400-meter race and 110-meter hurdles.

On Friday, the day on which all final races were to be run, the 100-meter was scheduled immediately before the 110-meter hurdles. Mr. Curtis's trainer held him out of the 100-meter to focus his energy on

the latter race. The trainer's caution paid off as Mr. Burke won the 100-meter by a foot and Curtis pulled off the 110-meter hurdles by twice that distance.

"As this was the race I had come especially to run, and as I had heard great tales of the prowess of my opponent and his many victories in England, I breathed much more freely and was able to look at the

other final contests with much greater pleasure," Mr. Curtis wrote.

When all the races were tallied, the Americans did exceedingly well, taking first place in nine of the 12 competitions. The prizes were awarded from a platform in front of the King of Greece's box. Here,

Curtis received an olive branch from the sacred grove of Olympus, a specially designed medal made from silver (gold medals were not awarded to first-place winners until later Olympics), and a "diploma" engraved in Greek with a description of his award.

In addition to his written account, Mr. Curtis provided a visual portrait of the 1896 Olympics. His camera, a gift from his parents, is the source of most of the photos of those games, according to the Los

Angeles Times.

------------------------------------------------

Other MIT Olympic medal winners:

- Joseph L. Levis '26, silver medal in fencing in 1932

- Ralph L. Evans Jr. '48, silver medal in sailing in 1948

Other MIT Olympians:

A number of MIT alumni have competed. MIT's most recent Olympic athlete, Alexis Photoiades '91, was a skier for Cyprus in the 1988 and 1992 Olympics. Other MIT Olympians include hurdler Henry Steinbrenner

'27, who competed in the 1928 Olympics. He is the father of George Steinbrenner, principal owner of the New York Yankees. MIT's Steinbrenner Stadium is named after him.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on August 28, 1996.