Commencement is perhaps the single most satisfying day at MIT for students and their families, but it's preceded by many days, weeks and months of meticulous planning to make sure the event lives up to expectations.

The process actually begins at the beginning of the academic year, when members of the MIT community start suggesting names for a Commencement speaker who is eventually chosen by President Charles M. Vest. Logistical planning for the big day has been in high gear since early spring. But organizers hope that much of their work-the planning for a backup site in case of bad weather-will prove to be unnecessary.

One of the most closely consulted people in the days before Commencement is weather advisor Kerry Emanuel, professor of earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences and director of the Center for Meteorology and Physical Oceanography. "We really get into [weather monitoring] on Thursday; by Thursday night, we pretty well know, but not all the time," said Mary Morrissey, director of special events and executive officer for Commencement. Among her many other tasks in the weeks leading up to the event are arranging for vendors (photographers, musicians and florists, to name a few), reserving rooms around campus in case events must be held indoors, and making sure everyone involved knows what they are supposed to do and when.

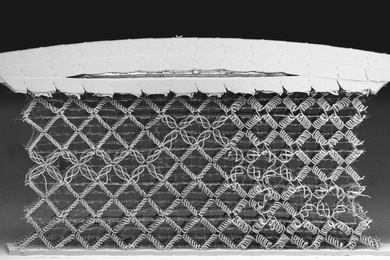

Even if the sun is shining on the morning of Commencement, the backup plan may have to be activated if the ground is soaked from earlier rain or if it is too hot for the comfort of the audience, she noted. However, since the ceremony was first held in Killian Court in 1979, it has had to be shifted indoors only once, in 1986 (ceremonies formerly were held in Rockwell Cage and in Symphony Hall before that). The speakers, MIT officers and all-important diplomas are protected from the sun or light rain by a sailcloth canopy designed by Jerome Milgram, professor of ocean engineering (see accompanying story).

Assembling the apparatus for Commencement falls to Physical Plant, which produces a detailed script outlining the many preparatory tasks and which people are responsible for carrying them out. There are large tasks that everyone sees, such as building the platform and audio-visual towers, painting and grounds-keeping work, but there are also dozens of smaller jobs to be done, such as setting up chairs (8,430 gold and 2,200 black), delivering the ceremonial MIT seal, shepherd's crook and mace in its mahogany box, installing telephone service in the court, taking 9,400 raincoats to four locations if needed, dusting the chairs, synchronizing clocks, storing a pitcher of water and glasses in the lectern, and stacking the diplomas on the tables, a task for which workers wear gloves.

In the week before Commencement, the deans and officers who will read off the names of degree recipients receive lists of names with phonetic spellings so they can rehearse and thus avoid mispronunciation. They must also get their timing down so as to allow about two seconds between each name. "The pacing is important. We want to maintain a rhythm, so it's like a cadence," Miss Morrissey said. This wasn't an issue before 1986, when degrees were first given out by two presenters at once. That change shaved almost an hour off the procedure, which had previously taken up to two hours, she said.

"We're always grateful to be able to read each student's name and give them real diplomas instead of some kind of blank, and having the undergraduates shake the president's hand," said Martin Schlecht, professor of electrical engineering and computer science and chair of the Commencement Committee. Approximate numbers of degrees and recipients last week were 2,250 degrees going to 2,000 students, including roughly 1,000 undergraduates.

At a university as large as MIT, handing out diplomas in this way calls for careful coordination to make sure each student receives the right one. A group of about 60 aides headed by six marshals and Arthur Smith, dean of undergraduate education and student affairs, keep close tabs on students as they arrive at the Johnson Athletic Center, line up in their assigned groups and march to Killian Court. "The Registrar's Office does yeoman work on that," Miss Morrissey said. "These aides are checking constantly, and they don't have that much time to work." There are usually several dozen students each year who say they will participate in Commencement but do not show up.

The lineup just prior to the procession is a high point of the day unknown to the spectators assembled in Killian Court. "There's an upswell of emotion and excitement in the room that you just can't imagine unless you're there," Professor Schlecht said. Once the ceremonies finally begin, organizers still can't relax; they must stay focused amid all the excitement and be ready to quickly deal with any last-minute glitches. "I never take anything for granted," Miss Morrissey said.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on June 7, 1995.