Milk may seem as wholesome a drink as there is, but it was not always so.

Consider the U.S. in the late 19th century. At the time, producers of milk — especially milk sold in U.S. cities — frequently watered it down. The resulting liquid was blended with chalk or plaster of Paris to appear more white. And that wasn’t the half of it: Milk often contained formaldehyde and a cleaning product called Borax. Thousands of people, including children, died from drinking milk.

Eventually, the federal government got around to cleaning up milk production, after landmark legislation in 1906. The safe milk we drink today is a result of that law. But getting to that point required a decades-long struggle by outraged advocates — among them Chicago activist Jane Addams, writer Upton Sinclair, and, not least, a crusading scientist named Harvey Washington Wiley, the chief chemist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

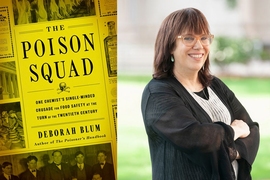

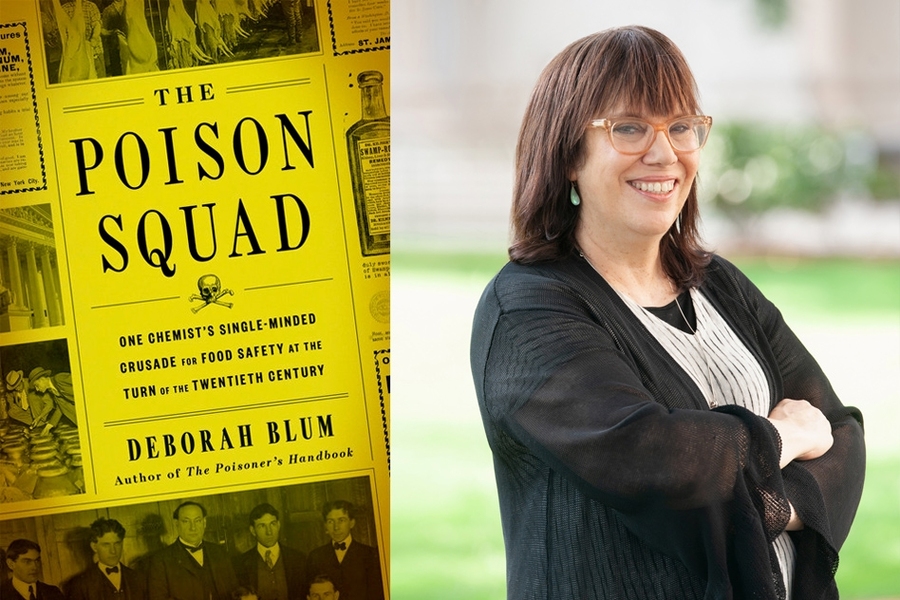

Wiley’s odyssey as a reformer and government official is at the center of a new book by MIT’s Deborah Blum, “The Poison Squad,” just published by Penguin Press. In it, Blum details the nascent 19th-century science and politics of food regulation, from the early efforts to figure out what dangers lay in food, to the torturous struggle to push regulations through the political system.

Wiley made headlines at the time through his efforts to reform food production and make eating safer for all Americans. Today, his legacy is little-known, which is a major reason why Blum wanted to reestablish his importance to us.

“I’m really interested in scientists who drive paradigm shifts,” says Blum, the director of the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT and author of several books on science research and the history of science. Wiley, she adds, was a “catalyst” without whom daily life would have been worse for tens of millions of people.

“I don’t mean the whole world was suddenly convulsed," Blum added. "But he changed the way people think. And that's a reminder that any of us can change the national or global conversation in a way that does good.”

A “really crazy experiment”

Wiley was an Indiana-bred, Harvard University-educated chemist who became an early faculty member at Purdue University. From there, after making his name through studies of multiple kinds of flawed food, he took his post at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

As Blum makes clear, there was plenty for food reformers to study. As food production became more industrialized in an urbanizing country, food fakery abounded. “Honey” was often corn syrup, and “vanilla” was often alcohol and food coloring. Coffee could contain sawdust, and brown sugar was notoriously spiked with crushed insects at times.

The book’s title stems from one project Wiley undertook, in which he recruited men in their 20s — “the Poison Squad” — to eat three free meals a day. Some of those people were consuming food with laced with chemicals of uncertain effect, or other dubious ingredients.

“It’s this really crazy experiment you could never do today, in which a government scientist persuades government employees to dine really dangerously,” Blum notes.

Eventually Wiley — and others — amassed plenty of evidence showing that food regulations were necessary. Getting such legislation passed was a saga of its own, and as Blum details in the book, Wiley had a strained relationship with Theodore Roosevelt, the president who ultimately signed the laws Wiley had been fighting for. In theory, these two reformers might have seemed natural allies. In practice, relations between them were fraught.

“Here you have two men who are both progressive and who both want to change the country for better, and who both believe that the current system of poorly regulated industry and business is doing a disservice to the country,” Blum observes. “So you would expect them to be on the same page, but in fact they clashed from the beginning. … I think basically Roosevelt didn’t like him. And that worked against him [Wiley]. He charmed a lot of people, but he never charmed Teddy Roosevelt.”

One reason for this, Blum suggests, is that while Roosevelt was famous for breaking up monopolies, he was in fact fairly comfortable with big business, under the right conditions. But Wiley was, long before it became more fashionable, a relentless consumer advocate, above all. His unyielding consumer focus did not correspond to Roosevelt’s priorities as much as the president’s reputation might suggest.

“I had to fight my way back to liking Teddy Roosevelt after doing the book,” Blum says.

An education in history

The book, Blum’s eighth, has received praise from experts. Melinda Cep, senior director of policy for the World Wildlife Fund’s U.S. Markets and Food team, has called it “a timely tale about how scientists and citizens can work together on meaningful consumer protections.”

For her part, Blum also says she hopes readers come away from “The Poison Squad” thinking that it has “all kinds of lessons for today” about both the discovery of diluted food products and the enforcement issues that arise once laws are passed. A significant part of Blum’s book, for that matter, scrutinizes the enforcement challenges that arose after the food safety legislation was passed.

To be sure, cases of deception in food production are still with us — many kinds of seafood, for example, are not what they appear on the label. Then there are grey areas, where older laws “are completely inadequate for the 21st century,” as Blum puts it, due to changes in the way food is produced.

Many kinds of drinks do not fully list their ingredients, for instance, due to policy compromises between regulators and industry that allow manufacturers to keep ingredients as proprietary information.

“Natural flavorings,” says Blum. “What are they? You’re never going to know.”

Researching and writing the book, Blum says, was thus instructive to her about the progress of science, as well as the tensions and conflicts that have existed among corporations, consumers, and government — and still do.

“It was an education for me,” Blum says. “An education in American history.”