Contrary to appearances at times, Europeans have become more receptive to immigration in recent decades. That’s one of multiple new findings from an innovative study on European public opinon co-authored by an MIT political scientist.

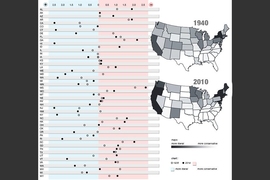

The study aggregates public opinion polls from 27 countries over a span of 36 years, offering new insight into broad trends and changes in European politics and society. While some dramatic recent political events, such as Britain’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union, have highlighted anti-immigrant sentiment, the overall picture looks rather different.

“There has been a general liberalizing trend on immigration, which is contrary to a lot of rhetoric and commentary,” says Devin Caughey, an associate professor of political science at MIT and co-author of the study. “Europeans, on average, when you ask them the same questions over time, have given more pro-immigration answers than they did a generation ago.”

As Caughey notes, that may be due to “generational replacement,” as older citizens who view immigration less favorably may be replaced by younger, more pro-immigrant cohorts of people.

The study also suggests European public opinion features a gender gap in a couple of areas. On economic policy, women throughout the continent have favored a more expansive state role during the study’s time period, which runs from 1981 through 2016.

“There’s [long] been this gender gap on economics,” Caughey says. “Women have always been less conservative than men, throughout the period we have. They are always more supportive of welfare spending or government responsibilities for the needy or unemployed.”

In recent years, a gender gap also seems to be opening up on a variety of social issues, including gender equity, gay rights, and abortion rights. However, as the authors note in the paper, this disparity is “much less pronounced” on social issues than on economic matters.

The paper, “Policy Ideology in European Mass Publics, 1981-2016,” has been published online by the American Political Science Review. In addition to Caughey, the authors are Tom O’Grady PhD ’17, an assistant professor in quantitative political science at University College London, and Christopher Warshaw, an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University.

The research on the project began while O’Grady was a doctoral candidate in the MIT Department of Political Science; Warshaw was a faculty member in the department at the time as well.

European geopolitics: The big split

To conduct the study, the researchers built a comprehensive database of multinational, ongoing political surveys conducted in Europe from 1981 to 2016. That includes the European Social Survey, the European Values Survey, parts of the International Social Survey Program, the Pew Global Attitudes Survey, and some Eurobarometer surveys. Overall, the study encompassed about 2.7 million individual survey responses to 109 different questions.

Examining data at such a large scale produced some broad insights, such as differing patterns in public opinion among different regions of Europe.

“There is this very clear geographic cleavage,” Caughey says. “Northern and western Europe tend to be relatively conservative on economic issues, and relatively progressive on social and cultural and immigration issues. The old Eastern Bloc and southern Europe generally tends to be pretty socially conservative, but much more comfortable with a strong government intervention in the economy. Which makes [historical] sense when you’re talking about the former communist countries.”

Given these nuances, the scholars decided not to measure the political views of Europeans along a simple ideological spectrum, such as by asking survey respondents where they place themselves on a left-right “self-placement” scale.

“That is measuring how people conceive of themselves and their identities, as much as their policy preferences,” Caughey says.

Instead, the researchers measured political views in four broad categories: absolute economic views, relative economic views, social issues, and immigration matters. On economic policy, an “absolute” economic view concerns, say, the objective size of a country’s welfare state. A “relative” economic view is whether someone would like to change the size of that welfare state. These things are sometimes conflated in accounts of public opinion.

Thus people in Denmark and Latvia, for instance, have similar views about the ideal absolute size of the state. But as the study shows, citizens of Denmark, whose welfare state is already more expansive than Latvia’s, express much greater relative conservatism.

Immigration and polarization

The researchers also decided to put immigration in its own political category, in part to examine how closely views on the matter connect with other political and social positions.

“They are associated,” Caughey says. “At any given point in time a country that tends to be conservative on immigration, relatively anti-immigrant, and relatively nationalist, also tends to be socially conservative. But they do exhibit somewhat different patterns over time.”

The dynamics of public opinion on immigration are also complex: As immigration becomes a higher-profile issue, a rise in anti-immigration sentiment may also be accompanied by a rise in distinctly pro-immigrant views, and increased political polarization on the subject.

“It’s possible that where immigration was a low-salience issue, then becomes a salient issue, and anti-immigration parties arise, other people react to that and become more fervent to their pro-immigration views,” Caughey notes. “For [some] people now, being pro-immigrant is a statement of progressive identity. … So there is an interesting interplay between the rise of anti-immigrant parties and the reaction against them.”

Other academic experts on public opinion say the paper is a useful contribution to the field. James Stimson, the Raymond Dawson Distinguished Bicentennial Professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina, helped advance the discipline with his own research tracking shifts in public opinion over time. Stimson says the approach of the authors to European public opinion “effectively gets more information from the same [existing] data and makes it possible to construct multiple measures for multiple countries. That extension is their unique contribution and an important one.”

For his part, Caughey says the researchers hope their current paper will help generate additional research about European public opinion, in which scholars might evaluate changes in public opinion against issues like changes in secularism or government responsiveness to popular opinion.