Metal-air batteries are one of the lightest and most compact types of batteries available, but they can have a major limitation: When not in use, they degrade quickly, as corrosion eats away at their metal electrodes. Now, MIT researchers have found a way to substantially reduce that corrosion, making it possible for such batteries to have much longer shelf lives.

While typical rechargeable lithium-ion batteries only lose about 5 percent of their charge after a month of storage, they are too costly, bulky, or heavy for many applications. Primary (nonrechargeable) aluminum-air batteries are much less expensive and more compact and lightweight, but they can lose 80 percent of their charge a month.

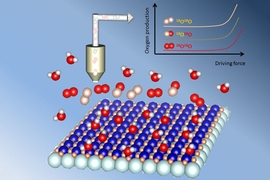

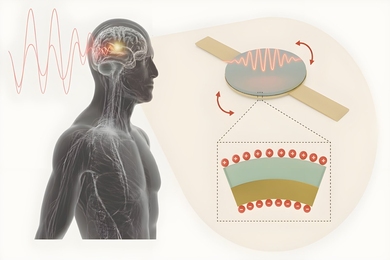

The MIT design overcomes the problem of corrosion in aluminum-air batteries by introducing an oil barrier between the aluminum electrode and the electrolyte — the fluid between the two battery electrodes that eats away at the aluminum when the battery is on standby. The oil is rapidly pumped away and replaced with electrolyte as soon as the battery is used. As a result, the energy loss is cut to just 0.02 percent a month — more than a thousandfold improvement.

The findings are reported today in the journal Science by former MIT graduate student Brandon J. Hopkins ’18, W.M. Keck Professor of Energy Yang Shao-Horn, and professor of mechanical engineering Douglas P. Hart.

While several other methods have been used to extend the shelf life of metal-air batteries (which can use other metals such as sodium, lithium, magnesium, zinc, or iron), these methods can sacrifice performance Hopkins says. Most of the other approaches involve replacing the electrolyte with a different, less corrosive chemical formulation, but these alternatives drastically reduce the battery power.

Other methods involve pumping the liquid electrolyte out during storage and back in before use. These methods still enable significant corrosion and can clog plumbing systems in the battery pack. Because aluminum is hydrophilic (water-attracting) even after electrolyte is drained out of the pack, the remaining electrolyte will cling to the aluminum electrode surfaces. “The batteries have complex structures, so there are many corners for electrolyte to get caught in,” which results in continued corrosion, Hopkins explains.

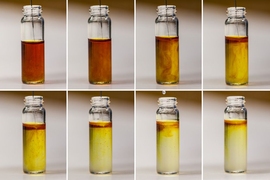

To demonstrate the ability of aluminum to repel oil underwater, the researchers plunged this sample of aluminum into a beaker containing a layer of oil floating on water. When the sample enters the water layer, all the oil that clung to the surface on the way down quickly falls away, showing its property of underwater oleophobicity. Courtesy of the researchers.

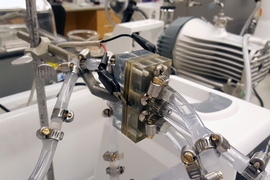

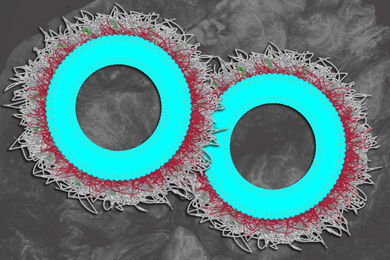

A key to the new system is a thin membrane placed between the battery electrodes. When the battery is in use, both sides of the membrane are filled with a liquid electrolyte, but when the battery is put on standby, oil is pumped into the side closest to the aluminum electrode, which protects the aluminum surface from the electrolyte on the other side of the membrane.

The new battery system also takes advantage of a property of aluminum called “underwater oleophobicity” — that is, when aluminum is immersed in water, it repels oil from its surface. As a result, when the battery is reactivated and electrolyte is pumped back in, the electrolyte easily displaces the oil from the aluminum surface, which restores the power capabilities of the battery. Ironically, the MIT method of corrosion suppression exploits the same property of aluminum that promotes corrosion in conventional systems.

The result is an aluminum-air prototype with a much longer shelf life than that of conventional aluminum-air batteries. The researchers showed that when the battery was repeatedly used and then put on standby for one to two days, the MIT design lasted 24 days, while the conventional design lasted for only three. Even when oil and a pumping system are included in scaled-up primary aluminum-air battery packs, they are still five times lighter and twice as compact as rechargeable lithium-ion battery packs for electric vehicles, the researchers report.

Hart explains that aluminum, besides being very inexpensive, is one of the “highest chemical energy-density storage materials we know of” — that is, it is able to store and deliver more energy per pound than almost anything else, with only bromines, which are expensive and hazardous, being comparable. He says many experts think aluminum-air batteries may be the only viable replacement for lithium-ion batteries and for gasoline in cars.

Aluminum-air batteries have been used as range extenders for electric vehicles to supplement built-in rechargeable batteries, to add many extra miles of driving when the built-in battery runs out. They are also sometimes used as power sources in remote locations or for some underwater vehicles. But while such batteries can be stored for long periods as long as they are unused, as soon as they are turned on for the first time, they start to degrade rapidly.

Such applications could greatly benefit from this new system, Hart explains, because with the existing versions, “you can’t really shut it off. You can flush it and delay the process, but you can’t really shut it off.” However, if the new system were used, for example, as a range extender in a car, “you could use it and then pull into your driveway and park it for a month, and then come back and still expect it to have a usable battery. … I really think this is a game-changer in terms of the use of these batteries.”

With the greater shelf life that could be afforded by this new system, the use of aluminum-air batteries could “extend beyond current niche applications,” says Hopkins. The team has already filed for patents on the process.

“The technique introduced here is eloquent in that it uses fundamental surface physics to estimate required oil and membrane properties, and the results demonstrate predicted performance,” says Robert Savinell, a professor of engineering at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, who was not involved in this research. “This work may indeed mitigate the need for costly high-purity metals and alloys for primary metal-air batteries, and might reduce the complexities of electrolyte additives.”

Savinell adds, “The ability to efficiently extract usable energy from high energy-density aluminum-air batteries, especially under intermittent use conditions, will facilitate the development and improvement of technologies requiring very high energy-densities for extended operation.”

The research was supported by MIT Lincoln Laboratory.