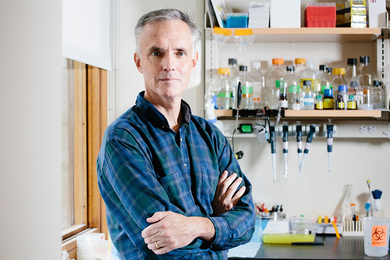

Professor Thomas A. Kochan has been studying work and employment in the United States for decades — and he thinks it is time for the country to make significant policy changes.

Kochan, the George M. Bunker Professor of Management and a professor of work and organization studies at the MIT Sloan School of Management, is a member of both the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future and the faculty steering committee for the Good Companies, Good Jobs Initiative at MIT Sloan. As one of his contributions to the Task Force on the Work of the Future, Kochan has just published a new research brief, "Worker Voice, Representation, and Implications for Public Policies." In it, he highlights some of his recent research on workers’ influence in the workplace and the kind of representation they’d prefer. Kochan also outlines proposed changes to U.S. labor policy that he believes will help the country achieve a future with broadly shared prosperity — and a new, more equitable social contract governing work. Kochan discusses some of this recent work here.

Q: You make the argument that updating America’s labor policies is an important aspect of preparing our society well for the future of work. Why is that?

A: America’s labor laws are woefully out of date. The basic labor law governing worker representation in the U.S., the National Labor Relations Act, was passed as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal in 1935. It worked well for many years for giving workers the opportunity to gain access to union membership and collective bargaining. However, today workers want not only collective bargaining but also an opportunity to influence how they work, both through informal processes in the workplace and through a role in corporate governance and decision-making. This is especially important if workers are to have a voice in shaping how technology is used to do work. Current U.S. labor law leaves those key decisions to employers, without any requirements for consultation with or advance notice to employees about the introduction of new technologies.

Q: What specific policy changes do you recommend?

A: There needs to be a major transformation of labor law and associated policies for improving worker-employer relationships. The changes need to start by fixing the basic failures of U.S. labor law to protect workers who want to form a union and establish a collective bargaining relationship. Penalties for companies that violate worker rights to organize (for example, by firing employees who protest company policies or speak out in favor of unionizing) need strengthening, and mediation and arbitration need to be available if initial contract negotiations reach an impasse. The law also needs to expand the rights of workers and their representatives to get advanced notice of new technology strategies and the right to discuss technology strategies and designs before they are implemented. Current labor law only gives workers the right to negotiate over the impacts of technological changes on working conditions, but that happens after the key decisions are made.

The law also needs to be opened up to allow for new forms of worker voice and representation, such as companywide “works councils” elected by employees, worker representation on company boards, and options for setting fair wage and other employment standards for government contractors. Finally, the many workers now protesting or using social media and other new ways of organizing outside of formal union and bargaining structures need protection from discrimination and retaliation. This is especially critical for those seeking a greater voice in the safety conditions at their workplaces and those raising their voices in support of racial justice.

Q: You also make the case that there should be greater collaboration between worker representatives and management in the United States. How might that work in practice?

A: Beyond these legislative changes, I strongly advocate a proactive national strategy for building and sustaining labor-management partnerships. Although they are currently relatively uncommon in the U.S., labor-management, such partnerships have demonstrated their ability to engage workers and employers in constructive, productive, and mutually beneficial relationships. For example, the health-care giant Kaiser Permanente has a labor-management partnership that involves frontline workers in continuous improvement efforts and has support from executive-level leaders in labor and management. That partnership is leading the way in using advancing technologies to improve patient care, responding in agile and flexible ways to meet the challenges of the Covid-19 crisis, and redeploying the workforce without resort to layoffs.

Congress should provide resources and hold the U.S. Secretary of Labor accountable for working to help diffuse labor-management partnerships across the country; this should be a primary responsibility of the Secretary of Labor, working in conjunction with other agencies such as the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service. In addition, educators should teach future managers and union leaders the skills needed to make these partnerships work.