As we get older, our endurance declines, in part because our blood vessels lose some of their capacity to deliver oxygen and nutrients to muscle tissue. An MIT-led research team has now found that it can reverse this age-related endurance loss in mice by treating them with a compound that promotes new blood vessel growth.

The study found that the compound, which re-activates longevity-linked proteins called sirtuins, promotes the growth of blood vessels and muscle, boosting the endurance of elderly mice by up to 80 percent.

If the findings translate to humans, this restoration of muscle mass could help to combat some of the effects of age-related frailty, which often lead to osteoporosis and other debilitating conditions.

“We’ll have to see if this plays out in people, but you may actually be able to rescue muscle mass in an aging population by this kind of intervention,” says Leonard Guarente, the Novartis Professor of Biology at MIT and one of the senior authors of the study. “There’s a lot of crosstalk between muscle and bone, so losing muscle mass ultimately can lead to loss of bone, osteoporosis, and frailty, which is a major problem in aging.”

The first author of the paper, which appears in Cell on March 22, is Abhirup Das, a former postdoc in Guarente’s lab who is now at the University of New South Wales in Australia. Other senior authors of the paper are David Sinclair, a professor at Harvard Medical School and the University of New South Wales, and Zolt Arany, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Race against time

In the early 1990s, Guarente discovered that sirtuins, a class of proteins found in nearly all animals, protect against the effects of aging in yeast. Since then, similar effects have been seen in many other organisms.

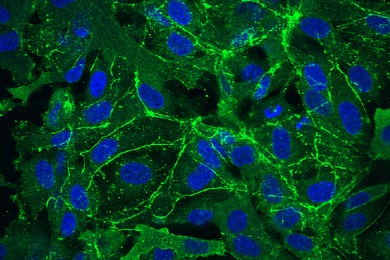

In their latest study, Guarente and his colleagues decided to explore the role of sirtuins in endothelial cells, which line the inside of blood vessels. To do that, they deleted the gene for SIRT1, which encodes the major mammalian sirtuin, in endothelial cells of mice. They found that at 6 months of age, these mice had reduced capillary density and could run only half as far as normal 6-month-old mice.

The researchers then decided to see what would happen if they boosted sirtuin levels in normal mice as they aged. They treated the mice with a compound called NMN, which is a precursor to NAD, a coenzyme that activates SIRT1. NAD levels normally drop as animals age, which is believed to be caused by a combination of reduced NAD production and faster NAD degradation.

After 18-month-old mice were treated with NMN for two months, their capillary density was restored to levels typically seen in young mice, and they experienced a 56 to 80 percent improvement in endurance. Beneficial effects were also seen in mice up to 32 months of age (comparable to humans in their 80s).

“In normal aging, the number of blood vessels goes down, so you lose the capacity to deliver nutrients and oxygen to tissues like muscle, and that contributes to decline,” Guarente says. “The effect of the precursors that boost NAD is to counteract the decline that occurs with normal aging, to reactivate SIRT1, and to restore function in endothelial cells to give rise to more blood vessels.”

These effects were enhanced when the researchers treated the mice with both NMN and hydrogen sulfide, another sirtuin activator.

Vittorio Sartorelli, chief of the Laboratory of Muscle Stem Cells and Gene Regulation at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, who was not involved in the research, described the experiments as “elegant and compelling.” He added that “it will be of interest and of clinical relevance to evaluate the effect of NMN and hydrogen sulfide on the vascularization of other organs such as the heart and brain, which are often damaged by acutely or chronically reduced blood flow.”

Benefits of exercise

The researchers also found that SIRT1 activity in endothelial cells is critical for the beneficial effects of exercise in young mice. In mice, exercise generally stimulates growth of new blood vessels and boosts muscle mass. However, when the researchers knocked out SIRT1 in endothelial cells of 10-month-old mice, then put them on a four-week treadmill running program, they found that the exercise did not produce the same gains seen in normal 10-month-old mice on the same training plan.

If validated in humans, the findings would suggest that boosting sirtuin levels may help older people retain their muscle mass with exercise, Guarente says. Studies in humans have shown that age-related muscle loss can be partially staved off with exercise, especially weight training.

“What this paper would suggest is that you may actually be able to rescue muscle mass in an aging population by this kind of intervention with an NAD precursor,” Guarente says.

In 2014, Guarente started a company called Elysium Health, which sells a dietary supplement containing a different precursor of NAD, known as NR, as well as a compound called pterostilbene, which is an activator of SIRT1.

The research was funded by the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, the Sinclair Gift Fund, a gift from Edward Schulak, and the National Institutes of Health.