In March 2011, as the disastrous accidents were unfolding at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan, Xingang Zhao was contemplating his next steps after completing a combined bachelor’s/master’s degree in energy and environmental engineering at the National Institute of Applied Sciences in Lyon, France.

The Nanjing, China, native had moved to France to study engineering with a focus on climate change. There, he zeroed in on low-carbon energy systems, driven by his interest in their global technological, economic, and social impacts. He learned that nuclear energy supplied a significant proportion of France’s electricity, and he became captivated by the sheer power generation at nuclear power plants.

“I was really passionate about the complexity of the nuclear systems. I couldn’t imagine how you could generate such a huge amount of power out of [a small reactor],” Zhao says. “[Nuclear energy] is really amazing, and it’s clean energy. In a low-carbon world, it should be a really useful energy source.”

But he wasn’t committed to pursuing graduate studies in nuclear engineering until the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disasters.

“I realized how important safety was not only for nuclear [systems], but also for human beings. Ten days after that disaster happened, I submitted my application” to a nuclear engineering program, Zhao recalls. “I said to myself, ‘Why don’t you study nuclear and try to make a contribution, to make nuclear reactors safer, to try to mitigate people’s concerns or fears?’”

Zhao went on to study nuclear engineering at the National Institute for Nuclear Science and Technology in France, where he tuned into the details of nuclear technology and the societal implications of nuclear energy development.

Now, Zhao is a fourth-year graduate student in MIT’s Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering, and he is on a quest to revamp nuclear energy safety measures to make nuclear technologies safer and more efficient.

Reassessing limits

During his early graduate studies at MIT, Zhao spent his summers interning at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. There, he was invited to work on modeling and simulating the flow physics and heat transfer of nuclear reactors for applications in safe operating guidelines, through the Consortium for Advanced Simulation of Light Water Reactors (CASL), the U.S. Department of Energy’s first innovation hub bridging basic research, engineering, and industry.

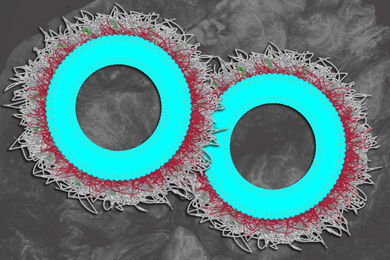

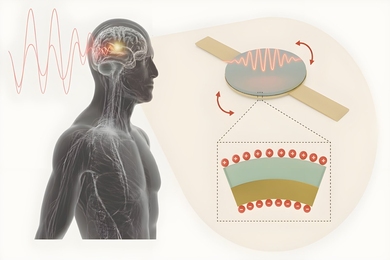

Zhao’s research is aimed at preventing a boiling crisis — an accident scenario in which nuclear fuel rods can no longer be effectively cooled during the heavy heat-producing energy generation process. Boiling crises can result in “a set of cascading failures,” and Zhao hopes his model will improve the methods used to predict them. “As engineers, we’re here to make sure this will never happen,” Zhao says.

However, he says, pressurized water reactors, which generate the majority of the electricity derived from nuclear power worldwide, are operating at parameters that are too conservative, compromising efficiency and energy output.

Currently, commercial nuclear reactors are required to operate at lower than three-fourths of their critical heat flux — the threshold at which a boiling crisis is triggered. “In nuclear, we like everything as conservative as possible,” Zhao says. But that cautious approach could come with a hidden cost: inefficiency. Zhao suspects that under some scenarios traditional models that calculate critical heat flux place it too low, meaning that the current nuclear reactor fleets are operating well under capacity.

To find out just how low, Zhao refers to the principles of physics.

“At the end of the day, nuclear engineering is all about physics,” Zhao says. By developing a physics-based approach that models how coolant flows around fuel rods, and validating it with recent experimental data, Zhao hopes to capture the true value of the critical heat fluxes for different reactors and allow them to operate more efficiently.

“In turn, that would have a positive impact for the profitability of your nuclear reactor, because that would enable you to provide more energy,” Zhao says. “Being able to provide more power without compromising safety and increasing costs makes nuclear energy more competitive.”

Impactful interactions

During his studies, Zhao took 22.312 (Engineering of Nuclear Reactors) and now considers it his favorite course at MIT. The course, taught by Jacopo Buongiorno, the TEPCO Professor and associate department head in nuclear science and engineering, covers the principles of nuclear reactor design, with a focus on the generation and removal of heat.

“Instead of showing slides, he put everything on the board, and made complicated subjects and concepts easily approachable,” Zhao says. Inspired by Buongiorno’s approach, Zhao aims to make his own research accessible for nonspecialists and easily applicable for the nuclear industry.

While 22.312 was required for Zhao’s field of study at MIT, he continued to take elective classes, even as recently as his fourth year. “For me, it’s not a burden,” Zhao says. “It’s more like, I learn things every day.”

Zhao credits his thesis advisor, Koroush Shirvan, assistant professor in the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering and MIT education program lead for CASL, with providing him with the mentorship necessary to pursue ambitious, computationally intensive doctoral research and classwork.

He and Shirvan regularly discuss challenges in not only research, but also daily life. “What makes him so great as a mentor, is that he’s smart himself and really cares about his students. But to me, he is more than that: He’s like a big brother to me,” Zhao says.

“I feel like MIT is more than an Institute. It’s like a family,” Zhao says. “And I really want to contribute to making this world a better place, by either working in academia or in a research-oriented laboratory or company. No matter where I would be, my intrinsic motivation will stay the same.”

In the long-term, Zhao hopes to make an impact on the international nuclear community.

“I think that in a new nuclear world, people from different countries have to collaborate more,” Zhao says. “We need to work together as a team and make nuclear energy safer and more affordable.”

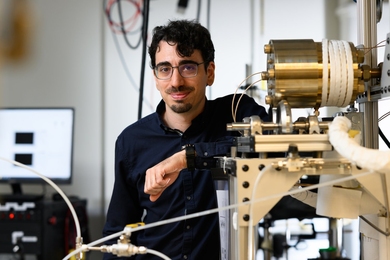

![“I was really passionate about the complexity of the nuclear systems. I couldn’t imagine how you could generate such a huge amount of power out of [a small reactor],” Zhao says.](/sites/default/files/styles/news_article__download/public/download/201807/MIT-Student-Zhao-02-PRESS.jpg?itok=wXn8X_Ng)

![“I was really passionate about the complexity of the nuclear systems. I couldn’t imagine how you could generate such a huge amount of power out of [a small reactor],” Zhao says.](/sites/default/files/styles/news_article__image_gallery/public/images/201807/MIT-Student-Zhao-01_0.jpg?itok=tVd9fQUc)