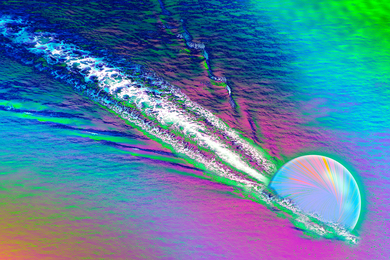

Each year the melting of the Charles River serves as a harbinger for warmer weather. Shortly thereafter is the return of budding trees, longer days, and flip-flops. For students of class 2.680 (Unmanned Marine Vehicle Autonomy, Sensing and Communications), the newly thawed river means it’s time to put months of hard work into practice.

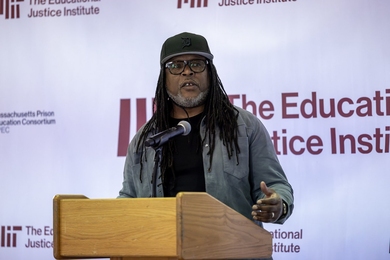

Aquatic environments like the Charles present challenges for robots because of the severely limited communication capabilities. “In underwater marine robotics, there is a unique need for artificial intelligence — it’s crucial,” says MIT Professor Henrik Schmidt, the course’s co-instructor. “And that is what we focus on in this class.”

The class, which is offered during spring semester, is structured around the presence of ice on the Charles. While the river is covered by a thick sheet of ice in February and into March, students are taught to code and program a remotely-piloted marine vehicle for a given mission. Students program with MOOS-IvP, an autonomy software used widely for industry and naval applications.

“They’re not working with a toy,” says Schmidt’s co-instructor, Research Scientist Michael Benjamin. “We feel it’s important that they learn how to extend the software — write their own sensor processing models and AI behavior. And then we set them loose on the Charles.”

As the students learn basic programming and software skills, they also develop a deeper understanding of ocean engineering. “The way I look at it, we are trying to clone the oceanographer and put our understanding of how the ocean works into the robot,” Schmidt adds. This means students learn the specifics of ocean environments — studying topics like oceanography or underwater acoustics.

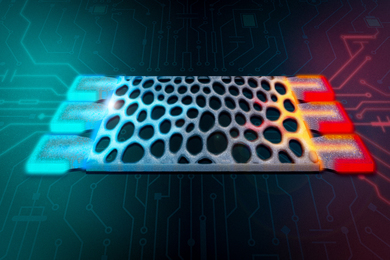

Students develop code for several missions they will conduct on the Charles River by the end of the semester. These missions include finding hazardous objects in the water, receiving simulated temperature and acoustic data along the river, and communicating with other vehicles.

“We learned a lot about the applications of these robots and some of the challenges that are faced in developing for ocean environments,” says Alicia Cabrera-Mino ’17, who took the course last spring.

Augmenting robotic marine vehicles with artificial intelligence is useful in a number of fields. It can help researchers gather data on temperature changes in our ocean, inform strategies to reverse global warming, traverse the 95 percent of our oceans that has yet to be explored, map seabeds, and further our understanding of oceanography.

According to graduate student Gregory Nannig, a former navigator in the U.S. Navy, adding AI capabilities to marine vehicles could also help avoid navigational accidents. “I think that it can really enable better decision making,” Nannig explains. “Just like the advent of radar or going from celestial navigation to GPS, we’ll now have artificial intelligence systems that can monitor things humans can’t.”

Students in 2.680 use their newly acquired coding skills to build such systems. Come spring, armed with the software they’ve spent months working on and a better understanding of ocean environments, they enter the MIT Sailing Pavilion prepared to test their artificial intelligence coding skills on the recently melted Charles River.

As marine vehicles glide along the Charles, executing missions based on the coding students have spent the better part of a semester perfecting, the mood is often one of exhilaration. “I’ve had students have big emotions when they see a bit of AI that they’ve created,” Benjamin recalls. “I’ve seen people call their parents from the dock.”

For this artificial intelligence to be effective in the water, students need to combine software skills with ocean engineering expertise. Schmidt and Benjamin have structured 2.680 to ensure students have a working knowledge of these twin pillars of robotic marine vehicle autonomy.

By combining these two research areas in their own research, Schmidt and Benjamin hope to create underwater robots that can go places humans simply cannot. “There are a lot of applications for better understanding and exploring our ocean if we can do it smartly with robots,” Benjamin adds.