Five years ago, at the first annual Online Learning Summit, the question being asked was “can we scale learning” to reach the vast population on the internet, said Sanjay Sarma, MIT’s vice president for open learning, in his introduction to this year’s summit. That’s no longer in question, he continued: “The answer is emphatically yes.”

Now, as the number of people taking online classes around the world has rocketed upward, the questions revolve around issues of how to carry out such online education, how to provide meaningful credentials for online classes, and how to integrate and complement online education with that offered on traditional residential campuses.

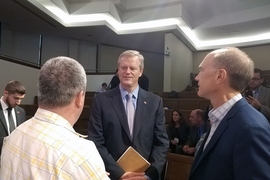

Introduced by MIT President L. Rafael Reif, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker delivered a keynote talk at the summit. The event took place Sept. 27-28 and drew administrators and professors from around the U.S. and elsewhere to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The summit has been jointly convened by MIT, Harvard University, the University of California at Berkeley, and Stanford University every year since 2013. The 2017 program included sessions on scaling various approaches, new types of credentials, diversity and inclusion, and academic integrity.

Baker described an innovative program that matches students from disadvantaged neighborhoods in the Boston area with mentors and a place to study, allowing the students to take classes from Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU), one of the largest providers of online accredited degrees. “I talked with a lot of these kids, and to a person, they said without a program like this, it wouldn’t happen,” Baker said, emphasizing the importance of combining in-person interaction with the online educational experience.

Online courses, combined with extra help for those who have fewer resources available, can be an important way to open up new career opportunities to people who might not be able to afford a traditional college degree, Baker said. For example, online classes allow students to fit classes around their own schedules while working full time or raising a family. For many people, “it’s either going to happen this way or not at all,” he said.

Citing booming enrollment in online classes, Baker noted, “You’re scratching an itch with this stuff.”

He told the story of a state employee who had worked his way up through the ranks of a state agency over many years, learning every aspect of how the agency functioned from the inside, and ending up as its deputy administrator. But when the administrator’s position opened up, even though everyone agreed this employee was by far the most qualified candidate, state regulations prevented his appointment because he lacked a college degree. For someone working full-time and supporting a family, taking time off for college had been out of the question, but the possibility of earning an accredited degree through online classes, at his own pace, could finally open the path to advancement for people in such situations, Baker said. “If [the Massachusetts state government] had something like a micromasters program available, we’d consider that to be the equivalent” of the required degree, he said.

Paul LeBlanc, president of SNHU, described the growth of that institution’s online education program, which now enrolls 100,000 students online, compared to 3,000 at its Manchester, New Hampshire, campus. “I would argue that now, the best online education is better than most traditionally delivered education,” he said.

For example, he said, while a student struggling with a particular concept in a traditional math class might learn it just well enough to pass a test, or miss it altogether and get a lower grade, an online learner could go back over the lecture as often as needed to really grasp it. Already, he said, “in lots of colleges, students aren’t even going to classes. They’re online learners.”

LeBlanc said that in a recent study comparing 4,000 SNHU online students who had earned 60 online credits — the equivalent of two years of college — with 7,000 students who had earned two-year degrees, the online learners “outperformed in every category” the traditional graduates.

And such education is accessible to anyone, anywhere, as long as they can get to a place with an internet connection, he said.

Yossi Sheffi, the Elisha Gray II Professor of Engineering Systems at MIT, who led MITx’s first online micromasters program, said teaching these online classes “is uplifting. We get people thanking us every morning.” He urged any of his fellow faculty members who hadn’t already done so to try teaching an online class. Most online students, he said, “have a real drive to do this, often under difficult conditions.”