Once upon a time, not so very long ago, scientists could only postulate at the existence of planets orbiting other suns. Today, the race is on to find the first with signs of life, and it's hot.

With so many planets out there, the observational exoplanetary-science community is fiercely focused on identifying the most promising candidates for the next phase of their search, for the select few that will be first in line to command time on advanced new spaceborne and larger ground-based telescopes, scheduled to come online in the next few years. Scientists hope by observing the atmospheres of these planets they will be able to detect biochemical signatures of life.

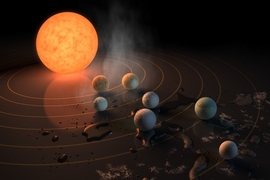

Now, as reported in the April 20 issue of Nature, a new, "super Earth" candidate orbiting in the habitable zone of a nearby small star has been identified. This latest planet joins Proxima Centauri b and the TRAPPIST planetary candidates reported in February, at the top of the list of most promising potentially habitable planets scientists have so far identified.

The paper was authored by MIT postdocs Jason Dittmann and Elizabeth Newton, along with a team of other American and European collaborators. Dittmann, a lead author of the study who is currently working with postdoc Sarah Ballard at the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, will be joining the group of MIT Professor Sara Seager in July as the inaugural Heising-Simons Pegasi B Fellow.

Located just 40 light-years away, the planet was found using the transit method, in which a star dims as a planet crosses in front of it as seen from Earth. By measuring how much light this planet blocks, the team determined that it is about 11,000 miles in diameter, or about 40 percent larger than Earth. The researchers have also weighed the planet and found it to be 6.6 times the mass of Earth, indicating it is dense and likely has a rocky composition.

The planet orbits a tiny, faint star known as LHS 1140, which is only one-fifth the size of the sun. Since the star is so dim and cool, its habitable zone (the distance at which a planet might be warm enough to hold liquid water) is very close. This planet, designated LHS 1140 b, orbits its star every 25 days. At that distance, it receives about half as much sunlight from its star as Earth.

What makes planets that transit their host stars, like this latest discovery and the other candidates before it, special is that they can be examined for the presence of an atmosphere. As each planet moves in front of its star, the star’s light is filtered through any atmosphere, the gases present modifying the spectrum. Scientists on Earth, soon to be armed with next-generation telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (scheduled for launch in 2018), and the ground-based Giant Magellan Telescope (currently under construction), are working to be able to tease out these subtle signals for evidence of biosignatures — chemicals that would suggest an alien planet is playing host to life.

As a lead author on the study, Jason Dittmann analyzed light curve and radial-velocity data and wrote the manuscript. Meanwhile, Elisabeth Newton determined the rotational period of the star. Both did their work as members of the MEarth research team at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics before joining MIT.

When Dittmann’s Pegasi-B Fellowship officially begins on July 1, he will join the group of Class of 1941 Professor of Planetary Sciences Sara Seager. Seager’s group is focused on the search for other Earths via space mission concepts and observations, modeling, and/or interpretation of exoplanet atmospheres, interiors, and biosignatures.

“All planets close to Earth mass or Earth size and anywhere near their star’s habitable zone (however ill-defined) are worth pursuing in the search for life on other worlds,” says Seager, who has appointments in the departments of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) and Physics. Seager is also a co-investigator on the MIT-led Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, a space telescope within NASA's Explorers program designed to search for exoplanets using the transit method that’s planned for launch in March 2018.

“I am delighted that the Heising-Simons Foundation chose MIT to host one of its four inaugural fellowships. Jason brings extensive expertise in exoplanet discovery that will be a huge asset to the MIT TESS team," Seager says.