MIT’s unique campus is home to 4,500 undergraduate students, but its reach extends far beyond Cambridge. As the Institute celebrates its first 100 years in Cambridge and prepares for the future, one of many challenges it faces is how to best serve students on campus as well as the many students who learn from MIT’s online educational initiatives but never set foot on campus.

“If online education is a first-class citizen in the educational landscape, the question is, what happens to the university, to the campus?” said Sanjay Sarma, MIT’s vice president for open learning and the Fred Fort Flowers and Daniel Fort Flowers Professor in Mechanical Engineering, at a symposium this week titled “The Campus — Then, Now, Next,” in Kresge Auditorium.

That question was among many posed at the event, which also addressed key challenges such as updating and preserving historical buildings, making the campus more sustainable, and redeveloping the MIT’s interface with the Kendall Square neighborhood. Leaders in campus design and educational innovation convened to discuss these topics as part of this spring’s ongoing celebration of the 100th anniversary of MIT’s move to its Cambridge campus.

“We are at a crossroads,” said Chancellor Cynthia Barnhart, who opened the event on Wednesday afternoon. “This is a moment of celebration as we reflect on our first 100 years in Cambridge and plan for our next 100.”

“Brilliant genius”

MIT’s original Cambridge campus, the cluster of buildings known as the Main Group, was designed by William Welles Bosworth. The campus’ layout, featuring interconnected buildings totaling 1 million square feet, was modeled on the “mega” buildings found at European universities such as the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH Zurich), said Mark Jarzombek, an MIT professor of the history and theory of architecture.

“We have here an astonishing building and one that has determined the robust character of the MIT ethos,” says Jarzombek, author of a 2004 book on the design of MIT’s campus, who reflected on that design during the symposium’s first session on Wednesday.

Jarzombek described several features that demonstrate Bosworth’s “complete and brilliant genius.” The base of the steps at the 77 Massachusetts Ave. entrance, he noted, curves slightly inward. This curve forms the arc of an imaginary circle whose center is at MIT’s heart, the Great Dome of Building 10. This subtle feature “propels you toward the center of campus,” Jarzombek said.

The dome itself was modeled on Rome’s Pantheon, but Bosworth elevated MIT’s dome so that it is much higher, allowing the iconic structure to be seen from across the river.

Jarzombek also pointed out that the columns at the Massachusetts Avenue entrance are fluted on their outward faces, as Ionic columns usually are, but the surfaces that face into Lobby 7 are smooth. This lack of fluting, as well as the fact that the lobby’s plinths have no statues atop them, suggest an element of unfinished work. Bosworth was essentially saying that upon entering the Institute, “We’ve got to get down to work. We don’t have time for flutes,” Jarzombek said.

From Lobby 7, one enters the Infinite Corridor, which Bosworth envisioned as both a portal to where the serious work of the Institute would be carried out and a meeting place for students, faculty, and staff. “It’s clearly designed as a social condenser,” Jarzombek said. “It’s a place where we can meet the chancellor, the president, students, tourists, and colleagues.”

Hilary Ballon, a professor of urban studies and architecture at New York University, described the role of university campuses in cities, where they serve as anchors for the surrounding urban environment.

“Cities recognize that universities play a central role in their economy,” she said, pointing out that universities are big employers, own a lot of real estate, and educate the workers needed for the knowledge economy. “Kendall Square is the perfect example of the paradigm of a university as anchor,” she said.

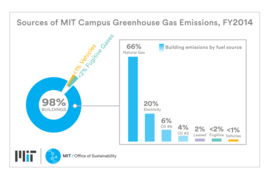

Universities like MIT also have an important role to play in developing and implementing more sustainable practices, said Julie Newman, director of MIT’s Office of Sustainability and a lecturer in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning.

MIT recently committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 32 percent by 2030. The Institute is also embarking on a capital renewal project with the goal of updating the original buildings and integrating sustainable practices all across campus. Those efforts may also serve as a model for other universities and institutions trying to address the challenges of climate change, Newman said.

“The goal of achieving a sustainable university is a transformative one,” she said. “MIT has the potential to profoundly impact the future of our campus and in turn, systems around the world.”

New opportunities

On Thursday, panelists discussed how the rise of online education may affect the relevance of physical campuses. Sarma noted that online education has evolved a great deal in the 15 years since MIT launched its OpenCourseWare initiative. More recently, MIT has joined with Harvard and many other universities to create the edX platform, which makes hundreds of courses available to students around the world for free.

This open access to education “creates opportunities that wouldn’t otherwise have existed,” Sarma said. In addition to extending educational opportunities to people who don’t have the money to pay for a traditional four-year college education, it also lets older learners finish college degrees or learn new skills they need for their jobs.

Paul LeBlanc, president of Southern New Hampshire University, which has extensive online programs, noted that online offerings tend to appeal to a different group of learners than the 18-year-olds who are seeking a traditional campus experience. More than 70 percent of the 70,000 people who take the school’s online courses are over the age of 21, and for these older, working students, “their first priority is their family, their second is work, and then they’re trying to squeeze in their education,” LeBlanc said.

Online programs can also help older learners continue developing new skills throughout their careers and help them to switch careers, said Anant Agarwal, the CEO of edX and a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT.

“It is senseless to think that what you learn for four years at age 18 will help you keep pace for the rest of your life,” said Agarwal, pointing out that industries such as data science have many unfilled jobs because there aren’t enough qualified workers.

To help address the needs of people who want to learn new skills, edX recently began offering a degree called a “MicroMaster’s,” which requires five courses followed by a capstone exam to demonstrate mastery of the subject.

One of the challenges still facing online education is how to replicate the experience of working together, as students in physical proximity often do. To help tackle this, edX recently launched a feature that allows students around the world to form teams that can work on projects together. “You can do all of this online, we just have to innovate,” Agarwal said. “We’re just scratching the surface of what is possible.”

Other panel discussions focused on experiments in education at the university, secondary, and childhood levels, and incubating urban innovation spaces such as Kendall Square.