Born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii, Lauren Uhr came to MIT for the research. Her first introduction to the Institute came through a research project she worked on in her hometown with John Chen ’84, a thoracic surgeon who studied chemical engineering and biology while at MIT. “Dr. Chen told me about his great experience at MIT and in Boston and encouraged me to apply,” Uhr says.

After visiting during the Campus Preview Weekend her senior year of high school, she was convinced. “When I visited, I just saw that everyone was so passionate about what they were doing, and there was such a wide range of interests,” she says.

“I also wanted to come to the East Coast for the seasons, and for a change of pace and lifestyle — I sort of regret the season part, especially when rowing on the Charles River in November,” she says, laughing.

Throughout her time at MIT, Uhr, now a senior, has pursued brain and cognitive research while working with patients in hospitals and study settings, and fueling her curiosity about global health and anthropology. “I am really interested in the way that culture mediates health and disease, and how one views their own body and own health,” she says. Perhaps not surprisingly, Uhr’s research interests have also been informed by her own life experiences.

Motivated research

Uhr began at MIT as a biology major, but after taking an introductory psychology course she switched to brain and cognitive sciences. Her personal experience with dyslexia has been a strong source of motivation in her studies.

“I was really interested in the brain ever since I was diagnosed with dyslexia,” she says. “I was frustrated that no one really knew, and no one could explain clearly, what was happening in my brain and how to fix it. I think that piqued my curiosity in the brain, and that’s why I decided to major in brain and cognitive sciences. It also pushed me to learn more about reading difficulties through research.”

Currently, Uhr is working on the READ Study, a collaboration between the laboratory of John Gabrieli at MIT and the laboratory of Nadine Gaab at Boston Children’s Hospital. The study seeks to establish a link between brain differences in kindergarten and reading difficulties in second grade, through MRI imaging and neurocognitive testing. Dyslexia is usually diagnosed in third grade or later, after students have already experienced difficulty or failed to read. “We are seeing if we can intervene and catch it at an earlier stage when interventions are more effective,” Uhr says.

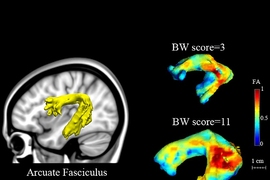

The study has partnered with 19 schools in the Boston area and follows students from kindergarten through second grade. Uhr has helped conduct MRI scans and is working on scoring neurocognitive tests and compiling the data. During these tests, students are asked to circle an inverted letter or number in a list, for example, or to match the spelling of common words such as “T-I-E” or “T-Y-E” with a picture of a necktie. So far, the MRI images have shown a correlation between poor phonological awareness in kindergartners and the size of a brain structure known as the arcuate fasciculus, which connects two language-processing centers. Whether the size of the structure is a result of the environment or of genetics is still unclear, but this brain region nonetheless provides a target for future research and possible intervention.

Uhr is also conducting a side project of her own to investigate the effects of early childhood environment — including factors such as socioeconomic status, hours spent reading to a child, and the number of books in a household — on the thickness of the brain’s cortex and children’s later reading development.

“What interventions are the most effective, and to whom?” asks Uhr. “This is personally important to me because I have dyslexia. It’s interesting — I have taken the tests that the study participants have, and now I’m on the other side of it.” Uhr, who was diagnosed in middle school, recalls struggling to keep up with reading and academic work, and learning ways to compensate with the support of her parents and teachers.

Gaining a global perspective

During the Independent Activities Program (IAP) last year, Uhr travelled to Pavia, Italy, with the MISTI Global Teaching Lab. She took an interactive approach to teaching chemistry and biology to high school students. “It was a great experience to share MIT’s approach to STEM education — hands on, experimental — with these students who normally receive a lecture-style education,” says Uhr. She has continued to teach, and is currently a teaching assistant for 9.20 (Animal Behavior).

Last spring, Uhr studied abroad at the Institute for Global Health at University College London. She originally discovered global health through her minor in anthropology. Working with MIT Global Education and Career Development, she crafted a study-abroad semester that would allow her to experience the universal health care system of the U.K. firsthand.

While in London, Uhr shadowed an infectious disease physician at St. Thomas Hospital. “That was a great experience because we treated everyone from a wealthy British woman to a homeless man with no address or insurance. It was really interesting to see that comprehensive access to medical care, but also at the same time I saw a lot of medical students protesting on the street about low wages and long hours. I really saw the pluses and minuses of the British National Health Service,” Uhr says.

Committed to service, research, and medicine

At MIT, Uhr has shadowed Emery Brown, the Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Medical Engineering, who studies the effects of anesthesia on the brain through electroencephalography. She also volunteers in the chemotherapy infusion unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, serving lunches to patients.

She works with Partners for Youth with Disabilities and mentors a 12-year-old girl with multiple neurocognitive disabilities. Uhr was also a mentor at the Massachusetts Youth Leadership Forum, a three-day conference for youth with disabilities to gain leadership and advocacy skills that would aid them in their future endeavors. At MIT, Uhr is an officer with MIT Project Connect, an organization that works with youth with disabilities in the community. Working with Boston University and Harvard University, the group hosts a Friday Night Club for children and young adults with disabilities at each of the college campuses — an evening of snacks, activities, and interacting with college students.

Uhr is applying to enter medical school in the next year and wants to pursue a specialty related to the brain: either anesthesiology or neurology. But she remains fascinated by the relationship between research and medical care.

“I find it interesting how research informs medical practice, and then there are always more uncertainties that come with advancements. That fuels a continual cycle of feedback between research and medical care, and I think that’s what really excites me, especially with the brain, because there are so many unknowns,” says Uhr. “I enjoy teaching and hope to have a career in an academic hospital where I can treat patients, conduct research, and teach aspiring doctors.”